Folk Portrait Artists

-

Edgar Adolphe (circa 1807-at least 1879)

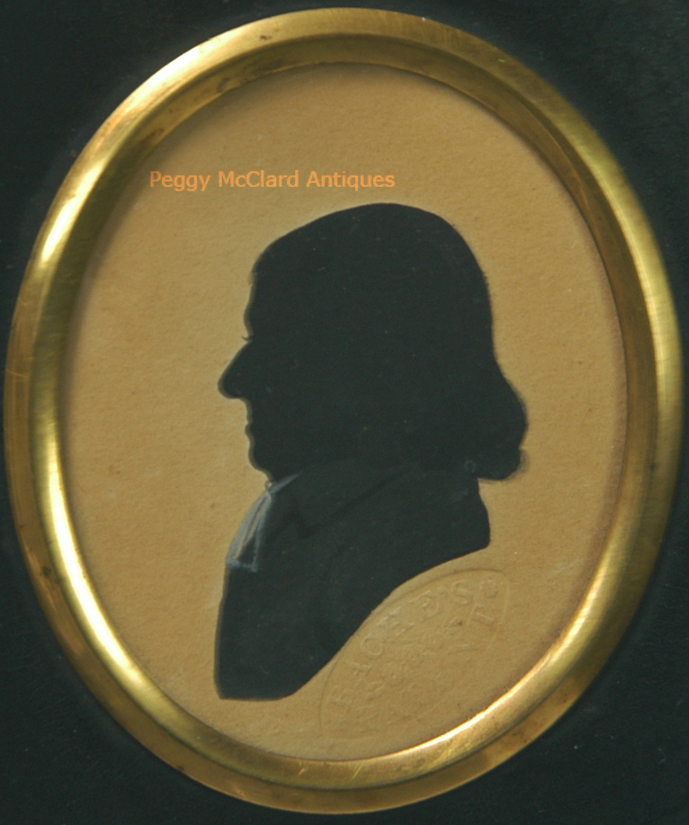

Most of what we know about Adolphe comes from his trade labels and profiles. Many of his trade labels refer to him as a a miniature and profile painter. A few full color portrait miniatures are known but most of his work seems to have been silhouettes. The earliest recorded work by him appears to have been done in 1832 and has a trade label proclaiming Adolphe as "Miniature Painter and Profilist to Louis Philippe, Kind of the French." Louis Philippe was King of France from 1830-1848. Since Adolphe appears to have left France for England by 1832 or earlier, Adolphe must have gotten his appointment as artist to the Court fairly soon after the Louis Philippe's accession. It is thought that Adolphe spent some time traveling and painting through England before he settled in Brighton no later than 1838.

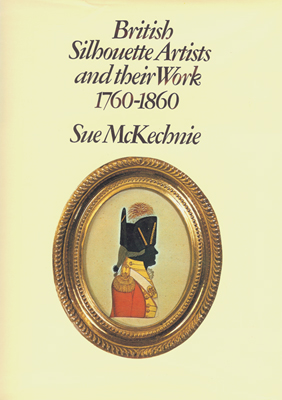

In British Silhouette Artists and their Work, McKechnie indicates that Adolphe probably worked in Brighton through the end of his career. He may have, but, if so, he must have changed careers because I found that he married Margaret Phibbs in 1856 in Dublin and still lived in Dublin without his wife in 1879. Since he was only about 50 years old in 1856, he must have still be working at some profession, even if not as an artist. Interestingly, I also found that Adolphe served 3 weeks in jail for libel in 1840 in Sussex.

A previously unrecorded trade label on the back of a circa 1840 silhouette gives the address 4, East St., Brighton, which was the last address that McKechnie found for him. According to McKechnie's book, Adolphe was listed in a business directory showing the East Street address, which was a tobacconist's shop that was managed by his first wife, Eloise. The trade label that I found states that, at 4, East St., Adolphe was working at the Manographic Institute. I have been unable to find any information about the Manographic Institute or of Adolphe's first wife, Eloise.

-

-

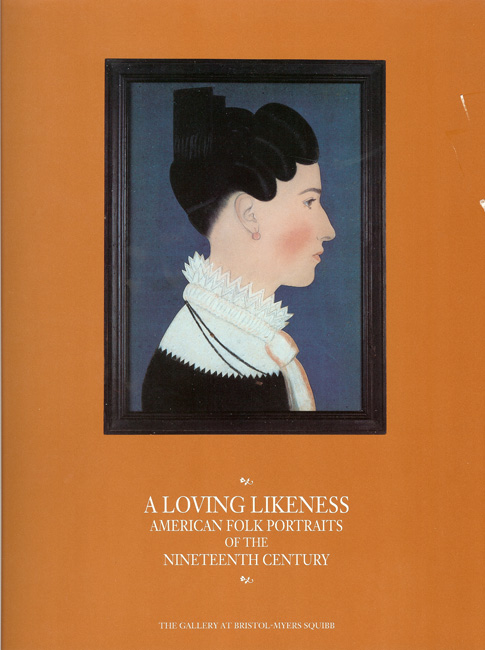

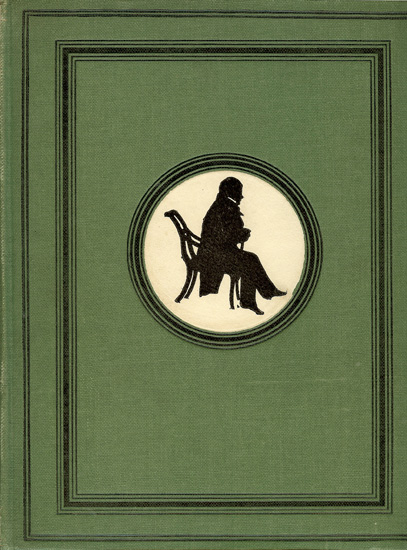

A Loving Likeness American Folk Portraits of the Nineteenth Century

This is one of my favorite books on folk portraits! This book represents the exhibit catalog of the 1992 exhibit of Raymond & Susan Egan's folk art collection at The Gallery at Bristol-Myers Squibb. It includes beautiful photographs of portraits and silhouettes of some of the most important American folk portrait artists of the 19th century. Brief biographical information is given for known artists within the collection as well as characteristics which help identify of the artist's work. The book is thin, but it has 60 information-packed pages and all of the many photos are in color. You will find yourself going back to this book over and over again for reference. If you collect folk portraits, you need this book!

This is a very good copy with a little scuffing to the covers and a slight crease in the top quarter of the back cover. Other than the minor cover scuffs, the book is in great condition with no marks to any pages. It does not have the supplement. Good copies of this book are getting increasingly hard to find and increasingly expensive. It's a great reference book!

(#4316) $70

This is a very good copy with the supplement. It has a mylar cover which is folded over the edges of the covers and taped down on the inside front and back cover. You could cut the tape and remove the cover--but it adds protection to the covers, so I would leave it where it is. The mylar cover has a wrinkle over the back cover. This book is becoming increasingly hard to find. It is nearly impossible to find any copy with the supplement, which is worth the extra money.

(#5549) $95

-

-

William Bache, American Silhouettist (1771-1845)

William Bache was born in Worcestershire, England but hurried to Philadelphia at the age of 22 years. He became established as a silhouettist almost as soon as he arrived and, later, traveled to the Southern States and West Indies to ply his trade as an itinerant artist. Bache and his partners, Augustus Day and Isaac Todd patented a physiognotrace in Baltimore in 1803. (See information about Day & Todd below.) Bache advertised "Cutting, shading and painting of profile likenesses in a new and elegant style from long experience and great success in business and aided by an improved Physiognotrace, feels confident of rendering general satisfaction." Bache surely delivered great satisfaction with his elegant hollow cut silhouettes, cut assuredly and made elegant with added India ink curls on the border of the cutting and Chinese white highlights added to the background paper. He referred to these stunning silhouettes as "shaded profiles." Bache also showed his artistic expertise with fully painted profiles, many which were reproduced in the 1920s and are now being offered as period silhouettes. We know through his scrapbook which descended through his family that he also cut many cut & paste silhouettes, although some naysayers believe that the silhouettes in Bache's duplicate books are "hole-in-the-donut" silhouettes (the middle "waste" of a hollow-cut silhouette). Scholars have basically debunked the hole-in-the-donut silhouette as mislabeled. Whether or not you believe that it is possible to cut a perfect hollow-cut silhouette and have a perfect image left afterwards without any trace of a scissor entry, the fact is that if a silhouette is cut as a positive image and pasted onto a background paper, it is a cut & paste silhouette. Part of Bache's scrapbook can be seen at the National Portrait Gallery's blog facetoface. The National Portrait Gallery acquired the books, which hold 1,846 images, numbered below each profile and the back of the book contains a partial index of sitters, identified by the numbers placed under the profile. I have also owned one of Bache's cut & paste silhouettes, on the reverse of a painted silhouette. The cut & paste was of the same figure on the obverse of the background card. Bache added his impressed stamp from the painted side, after he had pasted down the figure on the reverse. The impressed stamp is partially through the actual cut figure, showing in reverse.

In his short career, Bache cut or painted profiles of George and Martha Washington as well as Martha's daughter Mrs. Lawrence Lewis (née Nelly Cutis), Thomas Jefferson and Daniel Wadsworth, among others. Bache's career was cut short when, sometime between 1812 and 1822, a tree fell on him while chopping wood. As a result, Bache's right arm was amputated. Bache was appointed postmaster of Wellsboro, Pennsylvania and remained in that position until his death in 1845.

References:

Christman, Margaret C.S., Herein Hang a Tale, The Bache Silhouette Book", facetoface, National Portrait Gallery Smithsonian Institute, August 13, 2008.

Fallon, Rosemary & Lockshin, Nora, "Which Cracked First: The Inkin' or the Egg? Analysis and Treatment of Ink Deterioration in the William Bache Silhouette Album", The Book and Paper Group Annual 27 (2008), 123-24.

-

-

Ruth Henshaw Bascom (1772-1848)

Ruth Henshaw was born the oldest of 10 children, in Leicester, Massachusetts, to William (1735-1820) and Phebe Swan Henshaw (1753-1808). In 1804 at the age of 32, Ruth married Dr. Asa Miles (1762-1805) and moved to Westminster, Mass. He died a year after their marriage and Ruth returned to Leicester to by near to her family. During her time as a single widow, Ruth established a millinery business. Ruth married Rev. Lysander Bascom (1779-1841) in 1806 and moved to Phillipston where Rev. Bascom served as minister of the Congregational Church. Ruth never had children of her own but raised Bascom’s only child by his second marriage, Priscilla and the son of Bascom’s sister Eunice Loveland. In 1820, the Bascoms moved to Ashby, Massachusetts where Rev. Bascom served a church for 14 years. After Rev. Bascom’s retirement, he spent winters in Savannah, Georgia with his daughter for health reasons. Ruth, however, stayed in New England during those winters, visiting with friends and relatives while doing profiles. Around 1839 the Bascoms moved to Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire where the Reverend deems to have served a church on a semi-retired basis. He died in Fitzwilliam in 1841. Ruth spent her remaining years boarding in Ashby and traveling throughout Massachusetts and Maine. Rev. and Ruth Bascom are buried next to each other at Ashby First Parish Burial Ground. On her headstone is engraved the name “RUTHY H. BASCOM” and the note, “wife of Rev. E.L. Bascom, died Feb. 19, 1848, aged 75 years.”

Ruth Henshaw began keeping a diary in 1789 at the age of 14, and continued to do so for the rest of her life. She started a new volume every year and 54 volumes of her diaries were gifted to the American Antiquarian Society by Mary D. Thurston and Caroline Thurston in 1948. (The volumes for a few years are missing.) The diaries have provided scholars with a remarkably detailed description of everyday life of a New England woman in the 19th century and seemingly complete record of Bascom’s remarkably large body of artwork. Her diaries record nearly 1000 works of art.

Ruth’s first entry discussing the profiles that she drew and cut was made in 1801. The frequency of her discussions of profiles increases greatly in the 1820s and 1830s. There are only a few notations of receiving money for her sketches although scholars have written that Ruth stayed in New England during those winters when her husband went south not only to visit friends and relatives but to add to the finances of the family through her artwork.

Ruth’s profiles were made by placing her sitter before a paper and drawing the outline of the shadow. Unlike most silhouette artists of her day, Ruth did not attempt to reduce the size of the drawn profile, opting instead to fill it in with pastels (called crayons in the period). Her profiles have an abstract and soft feel achieved by her use of soft colors to fill in the precise outline and delineation of the ear, eye and a few other facial features. She sometimes added her own special touches such as cutting the profile out and placing it on a colored background or adding bits of tin or beads to the portrait as jewelry or buttons. Most of the backgrounds of Ruth’s work is done with a solid pastel crayon, she did some profiles on an abstract background of crayon. While we associate Bascom with full size pastel portraits, she also did some silhouettes. Of special note are 2 full-length, but reduced in size, cut and paste silhouettes of Chin-Sung, a Chinese teacher who spent several months in 1841 at Leicester Academy where he studied English. Her cut silhouettes of the young Chinese man in his “native costume” are very detailed and the departure from her usual full-size pastel profiles is her interest in his clothing. Chin-Sung captured interest everywhere. He also visited Washington, DC where his silhouette was taken by master silhouettist Augustin Edouart. Bascom’s silhouettes of Chin-Sung are in the collection of Old Sturbridge Village.

References:

Avigad, Lois S., "Ruth Henshaw Bascom: A Youthful Viewpoint", The Clarion Vol. 12, No. 4 (Fall 1987) Museum of American Folk Art,, New York, 1987. 35-41.

Bascom, Ruth Henshaw, Summary of Papers 1789-1848, American Antiquarian Society Manuscript Collections, http://www.americanantiquarian.org/Findingaids/ruth_henshaw_bascom.pdf

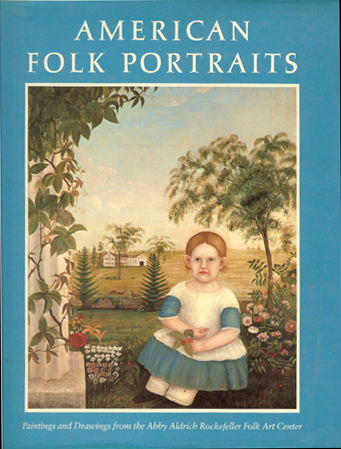

Rumsford, Beatrix, American Folk Portraits Paintings and Drawings from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Boston: Little Brown, in association with Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (1981). 49-50.

Sloat, Caroline F., ed., Meet Your Neighbors: New England Portraits, Painters & Society 1790-1850, Old Sturbridge Village, distr. University of Massachusetts Press, 1992. 74, 81-82, 100, 111, 119.

Please view the Ruth Henshaw Bascom currently in inventory on the Portraits page.

-

-

William Dyce (or Dyer) Beaumont (active c. 1833-1850)

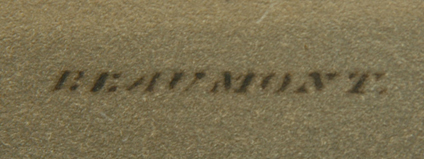

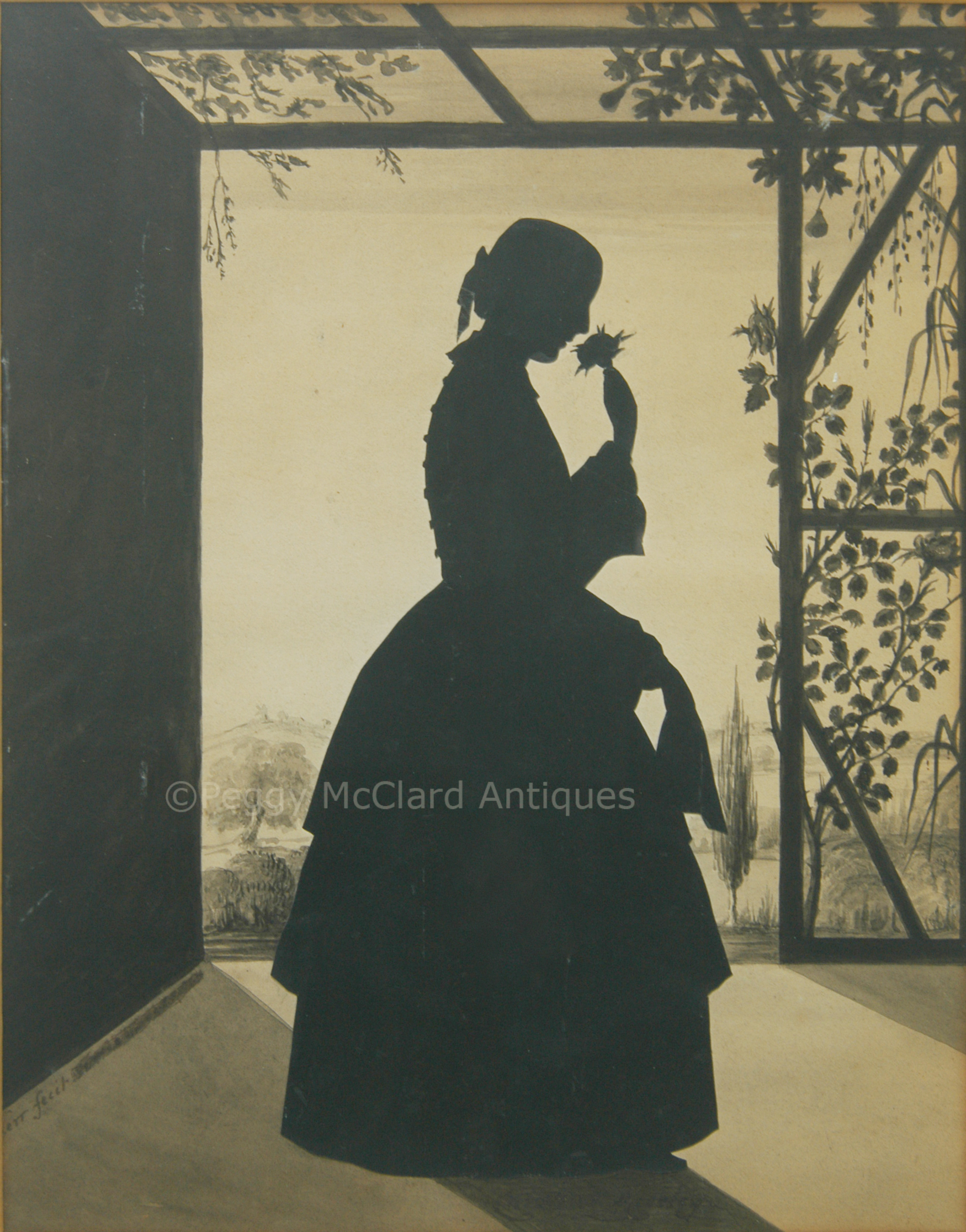

Beaumont's work is known for his use of sepia or dark brown paper from which he cut elegant and graceful women which he accented with subtle but highly unusual touches of color. Beaumont is known to have worked since the 1830s although his early work is not as successful as his later work. He cut men as well as women, but it is his women which are the most highly sought. His women were well placed with chairs of the early Victorian period and accessories such as ornate tea tables, stools, books, morocco-bound leather books, music scores, and sewing. Carpets are sometimes shown in color but to date we have no record of further painted backgrounds. His silhouettes of the 1840s and beyond has been called "among the finest of the period." McKechnie, Sue, British Silhouette Artists and their Work: 1760-1860 (Sotheby Park Bernet Publications, 1978) 190. Woodiwiss said, "Beaumont enjoyed using colour and always did so with the blending and discrimation of good taste. He arranged the details of his grouping with infinite care and his silhouettes may fairly be described as perfect examples of Victorian calm and breeding." Woodiwiss, John, British Silhouettes (Country Life Limited 1965) 68. According to McKechine is known to have signed his silhouettes "Beaumont", "W.H. Beaumont", W.H. Beaumont, fecit [date]." See McKechnie at page 190. In 2005, Diane Joll of the Silhouette Collectors Club reported that Christies sold Beaumont silhouettes signed, "W.D. Beaumont" and "Dyce Beaumont" so we all assumed that McKechnie was mistaken in saying that Beaumont signed with "H." Recently, a pair of silhouettes sold on ebay with the signatures "W. Dyer Beaumont, fecit, 1851". Therefore, we must also wonder whether Ms. Joll was mistaken (she included no photo of the Christie's silhouette signatures) or whether the pair on ebay had fake signatures (the signatures of the two pieces bore somewhat different handwriting). The simple neat signature "Beaumont" such as the one photographed on the right is well-recorded on the majority of Beaumont's work. One trade label has been recorded.

-

-

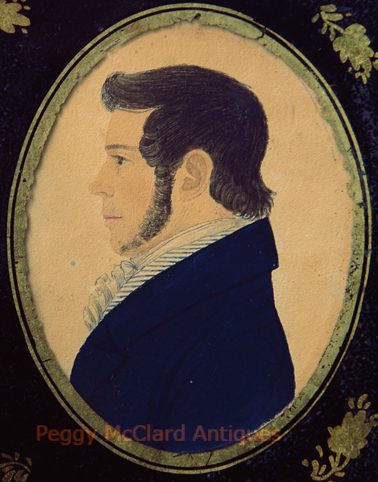

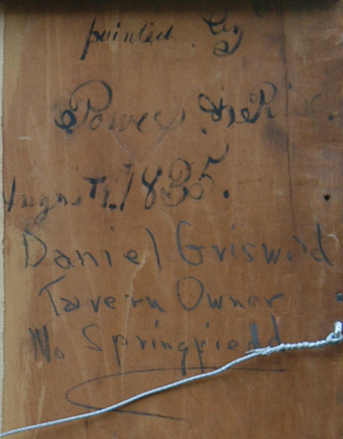

Zedekiah Belknap (1781-1858)

Zedekiah Belknap was born in Ward, Massachusetts (later renamed, Auburn) to Zedekiah (sometimes listed as Hezekiah) and Elizabeth (née Waite). He graduated, in 1807, from Dartmouth College where he studied divinity. The Catalogue of the officers and members of the Society of Social Friends, Dartmouth College, lists him as Reverend Zedekiah Belknap in 1839 and shows his residence as Boston. He married Sophia Sherwin of Maine, but there are no records of them having children. Belknap worked as an itinerant artist, painting portraits in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York and Vermont. There is no record of Belknap having received professional art training. His early paintings show an effort to paint in an academic manner. However, like many folk artists, Belknap soon developed a formulistic method of portrait painting that pleased his middle-class clientele. This formula allowed him to paint rapidly and efficiently.

His work is striking in that the mostly full-size images are bold and decorative. His sitters are boldly outlined with little modeling. His work is distinctive in that he always depicted only one side of the nose, outlining its profile with a heavy reddish shadow. The facial features are prominently depicted with full mouths, sharply outlined round eyes and flat, red ears. The women in his portraits are featured with strongly accented corkscrew curls, arched eyebrows, boldly painted lace and jewelry, giving these portraits strong decorative appeal.

Late in his career, Belknap began to depict his sitters in a more realistic, less decorative, manner. It is believed that this change in style was a reaction to popularity of the new daguerreotype which was overtaking the desire for more expensive portraits. His last known dated portrait is 1848, 10 years before his death. He ended his days on his farm in Springfield, Vermont, cared for by his sister and her husband.

Belknap's work is included in the collections of major art museums such as Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Fenimore Art Museum and The Detroit Institute of Arts.

References:

Baker, Mary Eva, Folklore of Springfield, Springfield, Vt.: The Altrurian Club, 1922, online at Ancestory.com.

Krashes, David, "An Appreciation of Nineteenth-Century Folk Portraits", Antiques & Fine Art Magazine online.

Rumsford, Beatrix, American Folk Portraits Paintings and Drawings from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Boston: Little Brown, in association with Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (1981) p. 57-60.

-

-

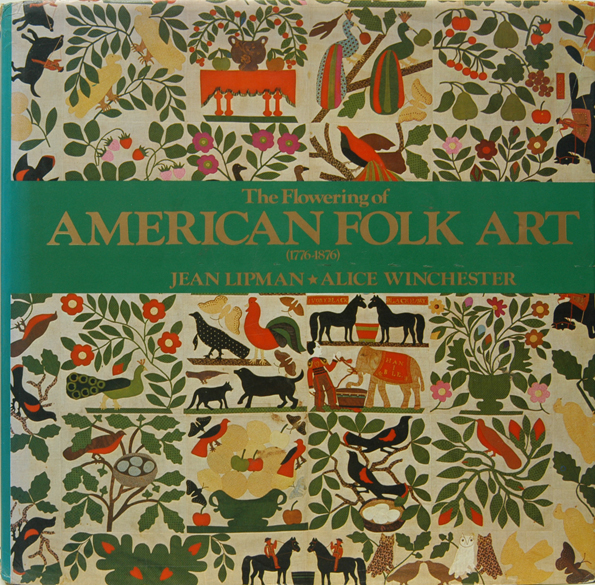

The Flowering of American Folk Art (1776-1876)

This is a landmark book of American folk art illustrating more than 400 outstanding examples of folk art produced during the period of its finest flowering. The objects shown in this book were selected from more than 10,000 examples owned by institutions, collectors, and dealers. This book documents the first major exhibition to survey the entire range of American folk art. Four major categories of works are represented: pictures that are painted, drawn, and stitched; sculpture; architectural decoration; and decorated household objects. Of the 400 illustrations, 100 are in color. Additionally, there are brief essays on each type of object; detailed captions for each work; biographical notes on the artist; and a selected bibliography. This is a go-to reference book for anyone who collects American folk art.

This copy is on fine condition a very good dust jacket. No markings on the pages, tight binding, just a touch of expected yellowing to the pages, especially at the edges. The dust jacket has tears at the binding edges (the dust jacket is not bound, I'm trying to say, the part of the dust jacket that covers the book binding).

(#5260) $25

-

-

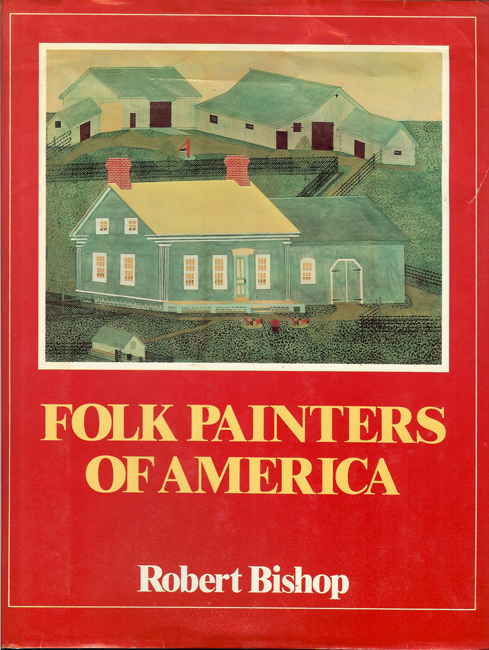

Folk Painters of America

Wonderful reference book of American folk painting of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. Bishop describes and illustrates two broad categories of folk painting: "pictures that recorded people, places, and time, and paintings that decorated essentially utiltarian objects, such as signs, fireboards, mantels, room ends, floors and floor carpets, windowshades, walls, ceilings, and furniture." This seminal book covers those two broad categories with wonderfully written text and more than 400 illustrations (70 in color). Chapters are split into geographical areas to help you identify trends that carried through the centuries in those areas. This is a wonderful book that I go to often in my research. It covers well-known and little-known artists. You'll love having it in your library.

This is a very good copy of the book with no markings on the pages and a good tight spine. The dust jacket is in good condition with scraping on the spine (of the dust jacket, not the book) and small tears and bends along the top and bottom edges.

(#5004) $25

-

-

John Brewster, Jr., (1766-1854)

John Brewster, Jr. (1766-1854) was born in Hampton, Connecticut to Dr. John Brewster and his first wife, Mary Durkee. John, Jr. was born deaf at a time when there was no established, commonly used sign language. This fact certainly made his chosen profession of itinerant painter even more challenging than the norm. But he had been born into a socially-connected family, and descended from Elder William Brewster, who led the Pilgrims to America on the Mayflower. His family connections allowed him to move easily between the socially elite of Connecticut, Maine and New York where he plied his trade as an itinerant artist. Brewster’s deafness certainly colored his world and influenced his art which is exhibited in many major museums. Art historians have labeled his paintings as “masterpieces” and “landmark” of American painting. In his book on Brewster, Harlan Lane argues that “Brewster was not an artist who incidentally was Deaf but rather a Deaf artist, one in a long tradition that owes many of its features and achievements to the fact that Deaf people, are,…, visual people.”1.

Brewster began his career as a painter around 1790, when he painted full-length portraits of his father and step-mother. He studied with a local artist, Reverend Joseph Steward who was influenced by the work of Ralph Earl. It appears that Earl’s work also influenced Brewster, however, Brewster developed a much simpler formula which became a backbone of American folk portraiture.

He moved to Maine with family members in 1796 and painted the majority of his identified portraits there. We know by his newspaper advertisements, that Brewster spent some of the first years of the 19th century in Newburyport, Massachusetts. He interrupted his painting for a time when, at the age of 51 in 1817, he entered the Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons in Hartford. His year of enrollment was the first year of the opening of the Connecticut Asylum, which was the first American school for the deaf. Brewster remained at the school for three years, during which he paid his own tuition, presumably from money earned with his painting. It was during Brewster’s time at the Connecticut Asylum that American Sign Language was developed.

Brewster’s portraits have long been recognized as some of the strongest likenesses produced by an itinerant artist during this period of the New Republic. His work is known for serene expressions, clearly delineated features and delicate flesh tones. It is said that the expressiveness with which Brewster painted the eyes of his subjects may be due to the great importance of eyes and sight to the deaf-mute artist.

1. Lane, Harlan, A deaf Artist in Early America, The Worlds of John Brewster Jr., Beacon Press, Boston, Massachusetts, 2004, xvi.

References:

American Folk Art Museum, Exhibition, A Deaf Artist in Early America: The Worlds of John Brewster Jr., October 4, 2006–January 7, 2007,

Cotter, Holland, “"Intense Visions by a Painter Who Couldn’t Hear”, New York Times, October 6, 2006,

Lane, Harlan, A deaf Artist in Early America, The Worlds of John Brewster Jr., Beacon Press, Boston, Massachusetts, 2004.

Please view the Brewster portrait miniature currently in stock on the Portraits page.

-

-

William Henry Brown, American Silhouettist (1808-1883)

William Henry Brown was born and died in Charleston, South Carolina. He worked as an engineer in Philadelphia where he lived from 1824 until at least 1841. He began his career as a silhouettist in the 1830s working first in New England and then traveling widely throughout the South. Brown pursued his career as an artist until at least 1859. After 1859, Brown is known to have resumed his work as an engineer.

Although Brown is often compared to Edouart, he began cutting silhouettes almost 15 years before Edouart ever set foot in America. Brown made his debut as a silhouettist in 1824 with a full-length silhouette of General Lafayette. Brown was a mere sixteen years old at the time. Like Hubard, Brown was considered a child prodigy. Also like Hubard and Edouart, Brown cut his silhouettes freehand with common scissors. His embellishment is subtle and superbly rendered.

Brown often mounted his silhouettes on lithograph backgrounds, made for him by the Kelloggs of Hartford. He is most well known for his book Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans published as a collection of full-length silhouettes with biographical sketches and letters written by the subjects. The book was published in 1846 by E.B. & E.C. Kellogg. Almost the entire edition was destroyed by fire and it is rare to find a complete copy of the book. Luckily, the Kelloggs also published the individual silhouettes from Brown’s book as lithographs. This lithography is most often what can be found on the market from Brown’s career. Original silhouettes are difficult to find despite the fact that Carrick believes he was as prolific as Edouart.

Besides the single figures that we most likely think of when hearing Brown’s name, he was a most industrious artist who cut profiles of an entire train, a fire brigade, and even a funeral procession. His silhouette of the St. Louis Fire brigade contained an engine, two hose carriages, and sixty-five firemen. The finished grouping was 25 feet long! Brown’s rendition of “The De Witt Clinton” train is over six feet long and may be viewed in the Connecticut Historical Society where it has hung since Brown presented it to the Society himself.

-

-

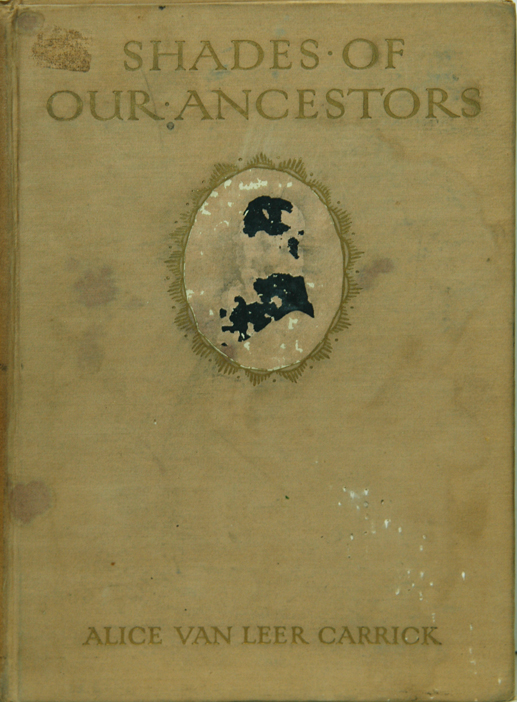

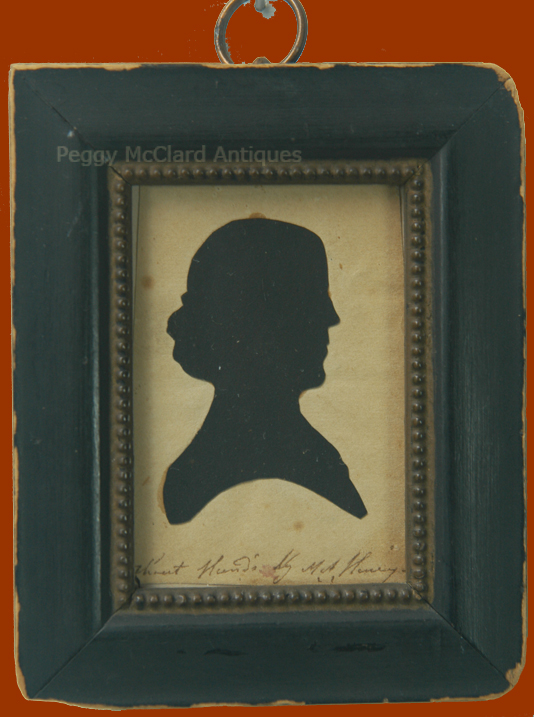

Shades of our Ancestors

One of my favorite books, a great read and a wonderful place to learn about American silhouettes and silhouette artists. Great reference material, lots of good black & white illustrations (plus one beautiful color frontpiece), and the stories will make you fall in love with American silhouettists. This is a very good reference copy with a good strong spine but the cover is not so pretty. The cover (which you see at the left) has most of the cover silhouette rubbed away. The cover is stained and dirty and the back cover has a large waterstain (see below). The pages to the front and rear of the book have expected yellowing but the majority of the pages are surprisingly bright. No markings on the pages that I can find. 1st edition. The book is becoming increasingly hard to find and it really is a good book to read and learn.

Sale Pending-

The back cover of the photo above.

The back cover of the photo above.

-

-

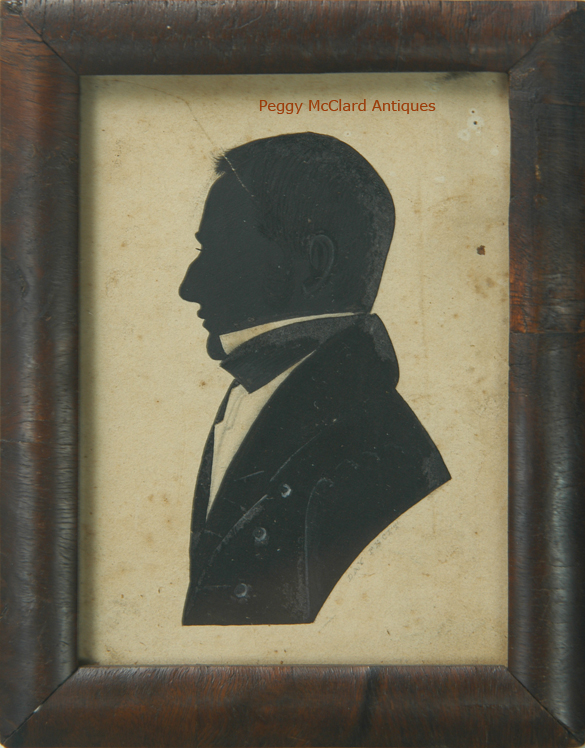

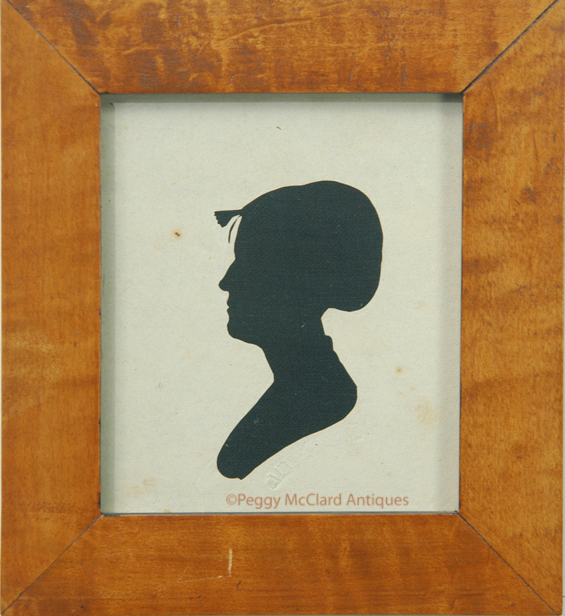

William Chamberlain, American Silhouettist (1790-1860)

Little is known about William Chamberlain although his silhouettes epitomize everything that is loved about American folk silhouettes.

Genealogy research tells us that he was born on April 3 (or 13), 1790, in Loudon, New Hampshire, the child of Captain Moses and Rebecca (Abbot) Chamberlain. He married Mary Ann Baker in 1813 or 1814. Together, they had one daughter, Mary Chamberlain, born in Loudon on August 28, 1835. In the 1850 census, Chamberlain listed himself as a chair-maker, leading us to speculate that either the life of an itinerant silhouettist was not profitable or that he wanted to find a way to stay home with his family. Chamberlain died at age 70 on April 13, 1860. He was buried in the Plains Cemetery, Boscawen, NH.

Carrick, in Shades of Our Ancestors tells us that Chamberlain went on a two-year silhouette cutting tour through Massachusetts, New Hampshire and New York. His grand-daughter, Mrs. Frederick McClure of Worcester, Massachusetts, gave to the American Antiquarian Society ("AAS") eighty-nine hollow-cut silhouettes done by Chamberlain and kept for himself. Chamberlain cut the donated silhouettes during a two year period in which he traveled New England in the 1820s, as an itinerant silhouette artist. Mrs. McClure added a note to her donation saying "He made the profiles with the aid of a profile machine. He usually cut his profiles in duplicate, and these are the ones he preserved." It is these eighty-nine silhouettes that allow us to attribute work to Chamberlain because he never signed nor stamped his work.

Chamberlain's work is hollow cut. He cut the heads of his men, left the collar and shirt front as an uncut part of the background paper, then cut the shoulder to the end of the bust-line. He then drew and painted the shirt and collar details. The women in his duplicate folio are completely hollow cut, from the top of the head to the bottom of the bust-line. I set about examining photocopies of the 89 silhouettes in the duplicate folio sent to me by the AAS and found that Chamberlain cut every silhouette in the folio with the same bust-termination line. Every silhouette that we know with certainty was cut by Chamberlain has a convex curve at the front of the bust-line, coming up at a notch, then a concave curve to the back.

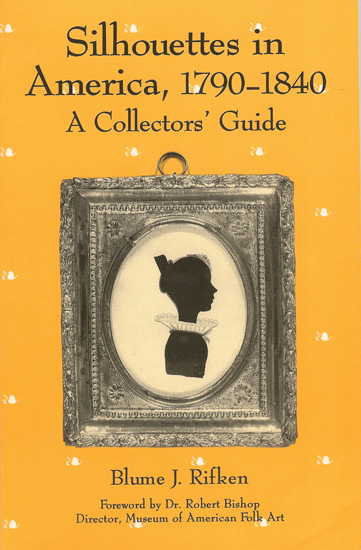

Almost every bust-length hollow cut man in which the collar and shirt front are left uncut with drawn-in details has been attributed to Chamberlain by uneducated dealers. Collectors should beware of such misattributions and look for examples of Chamberlain's work before spending a lot of money on a "Chamberlain" from a dealer who does not specialize in silhouettes. Examples may be found in Carrick's book and Silhouettes in America, 1790-1840 by Blume J. Rifken.1 I am currently offering a copy of both of the reference books on the Books page.

1After studying photocopies of the silhouettes in the Chamberlain duplicate book, I must disagree with Rifken's attribution to Chamberlain on pages 50-51. While Chamberlain might have cut those silhouettes, the bust termination is not the same as those in the duplicate book, which are the only ones we know with certainly were made by Chamberlain.

Please view the Chamberlain silhouettes currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

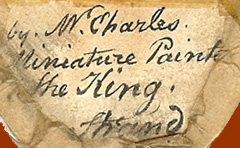

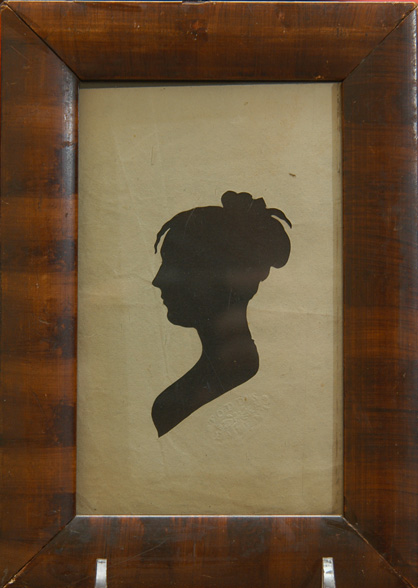

A. Charles (born circa 1768;active 1786-1807)

A. Charles is known for his portrait miniatures and silhouettes, which he painted on card, glass and on ivory. His story is interesting in that he seems to have perpetually elevated his standing in his advertisements. He advertised himself as the "Original Inventor of painting on glass", an endorsement that was, in all likelihood, not true. Although silhouettists and painters of the late 18th century were given to self-endorsement, Charles was a braggart to the point of drawing public criticism. He advertised that he was a Royal Academician, which he was not. He also advertised that he had studied "the Italian, Flemish, and all the great Schools," of which there is no confirming record. When he began to advertise himself as the artist to the Prince (which was a true statement) and raised his prices, a blistering criticism was printed in the London paper...which shows that Charles was definitely a well-known profilist who was in direct competition with the great John Miers and Mrs. Beetham. Had he been an artist who waltzed through life unnoticed, he might have gotten away with his boasts. Since he was obviously in the public eye and compared to his contemporaries, his boasting became a public embarrassment.

-

-

The Da Lee Family: Justus Da Lee (1793-1878), Amon G.J. Da Lee (1820-1879), Richard W.M. Da Lee (1809-1868)

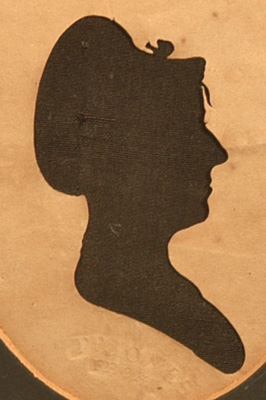

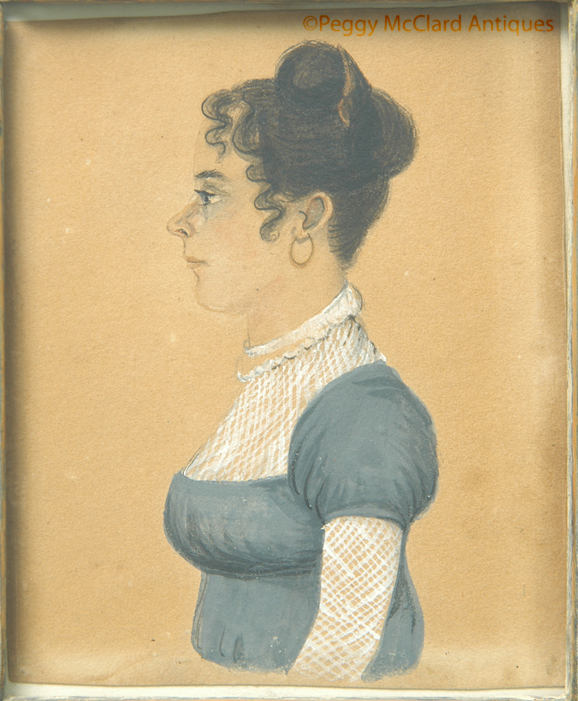

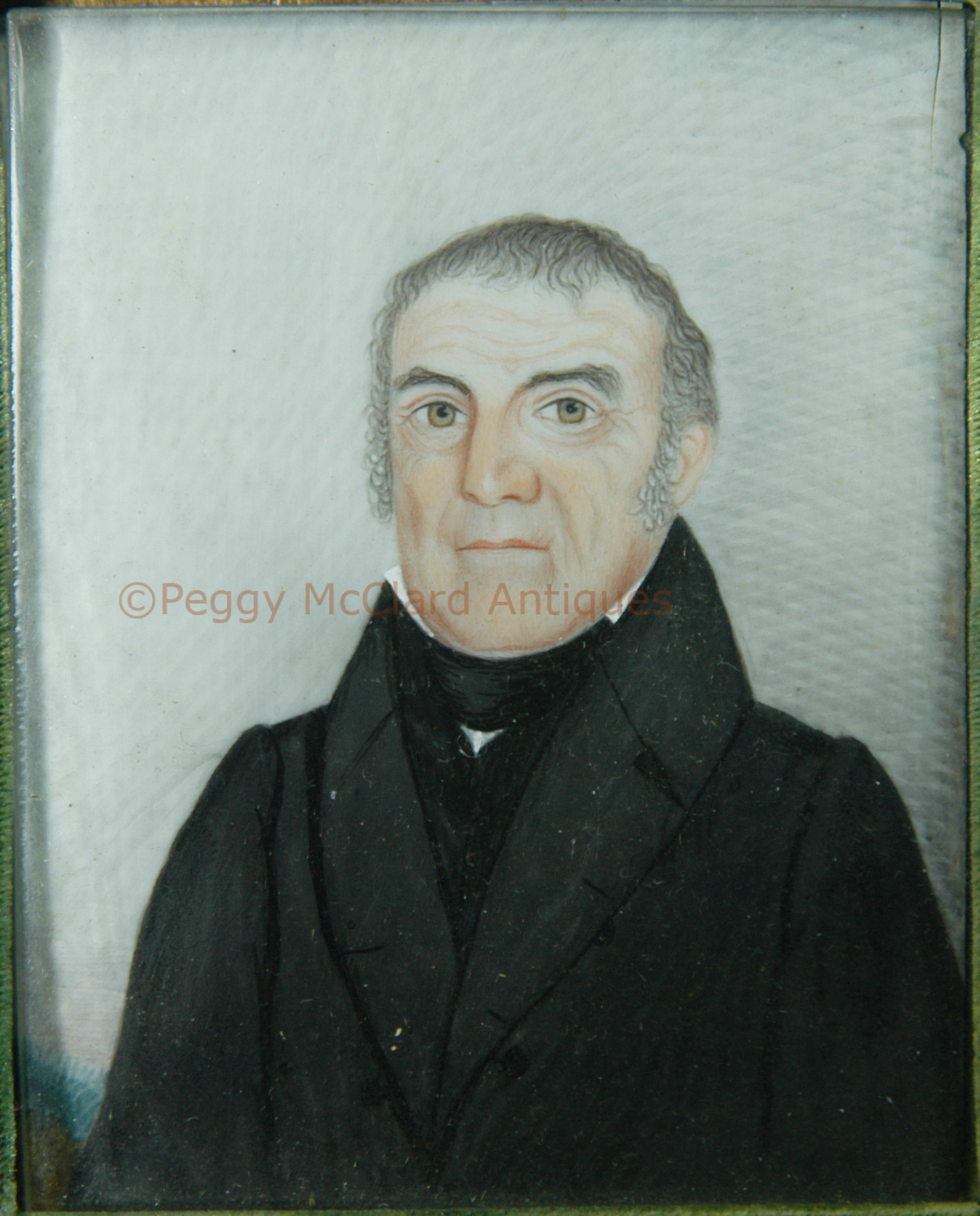

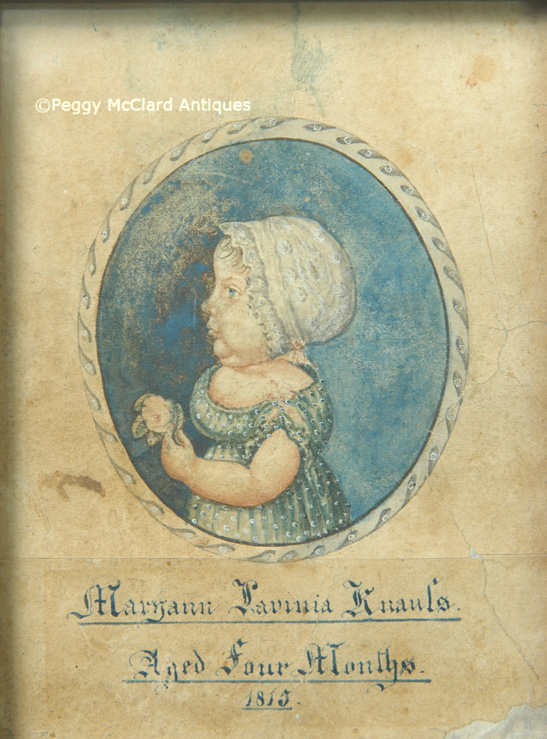

Long recognized as one of the great American folk art portrait artists, reliable information about Justus Da Lee and his family have only recently been published.1 Painstakingly rendered watercolor, pencil, and ink portrait miniatures, such as the one offered, and elaborate family records have long been attributed to Da Lee. Now we know that portrait painting was a family business in which Justus enlisted the help of his son Amon and his brother Richard. Born in Pittstown, New York, the obviously artistically inclined Justus enlisted in the Cambridge militia during the War of 1812, where he served as a musician. After his war duties, the highly educated Justus served as a school teacher until he lost his job for "usurping government." By 1826, Justus exhibited his artistic ability in a sketchbook entitled "Emblematical Figures, Representations & To Please The Eye." Justus referred to himself in the sketchbook as a "professor of penmanship."

Justus' painting career appears to have begun in the early-1830s. He painted a family record printed which he then further embellished with figures, flowers and decorative elements. It is at this time that he also began painting the distinctive small profile portraits for which he is best known. Justus taught his son Amon and his brother Richard to paint portraits. A 1837 letter from Justus to Richard states that painting had become a family business. Justus' own letters tell us that when he arrived in a new town, he distributed advertising cards to homes along a single street. The next day, he returned to the houses, showing samples and taking commissions. His prices were "3 dol. for a single one, set [framed]--or 5 dol. for husband & wife, set,' and a price of $2.50 each if the whole family was painted. Unlike most itinerant watercolor profilists of the era, Justus took his time painting the profiles stating "I detained some of them from 1 or 2 hours being determined to give the very best satisfaction." Perhaps it was the slow, deliberate perfectionist quality of the Da Lee work that brought about the end of the family portrait business.

Letters from Justus and from Richard show that they often complained that, although everyone was pleased with their work, their itinerant trips only took in a small amount of money. In 1845, Justus wrote "Amon . . . has given up going out to take ports anymore, it does not agree with him at all . . . this portrait business is calculated to kill us all." By 1848, two business directories in Buffalo, NY list Justus as an artist but also list Justus & Amon as grocers. Apparently, painting was no longer a full time occupation for the Da Lee family. The 1850 census lists Justus as a teacher and by 1856, records show that Justus was blind and penniless. He died in 1871 while living with his daughter Harriet in Wisconsin.

Thanks to the scholarship of Suzanne Rudnick Payne and Michael Payne, we now know that portraits previously attributed to Justus Da Lee must be attributed to the Justus Da Lee family. The Paynes tell us that known examples of work by Amon are "confusingly similar" to the work of Justus. There are no known signed examples of Richard's work but the portrait of Richard's son indicates that Richard's work was also very similar. Moreover, much of the work seems to have been a collaborative affair as Justus wrote in 1839 that Amon was painting the dresses and Justus was doing the rest of the portrait.

The Paynes describe the Da Lee portraits as follows:

"These small profile portraits were executed in watercolor, pencil, and ink with meticulous detail and delicacy using minute brushwork. A few portraits were painted on paper, but the vast majority was done on stiff bristol board, as it was called when the portraits were made. Ink and pencil were used to delineate the facial features and hair, and then watercolor was used to render flesh tones, hair, and clothing. Gum-arabic glazed highlights were used to further define the details of the clothing. Small details, such as jewelry and hair ornaments, were always so finely rendered that they invite examination with a magnifying glass. The portraits have an unusual delicacy and quality of detail."

The faces in adult portraits were always presented in profile. Men's bodies were always profile. A few of the earliest of the women's portraits were painted with a full frontal pose. By the 1840s the Da Lees were using both a three-quarter frontal and a profile pose for the women. Most of the portraits are contained within solid-black painted oval spandrels and many have blue wash along the inside of the spandrel. Although it has been surmised that the black painted spandrel was in the style of daguerreotypes, the Da Lees were using this format in the 1830s before daguerreotypes were widely offered.

References:

Anderson, Marna A Loving Likeness American Folk Portraits of the Nineteenth Century, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. (1992) 11-13.

Brownstein, Joan R. & Shushan, Elle, "Side Portrait Painters, Differentiating the DaLee Family Artists", The Magazine Antiques, July-August 2011. Click the link to read the pdf article posted on Elle Shushan's website.

Payne, Suzanne Rudnick and Michael Payne, "To Please The Eye Justus Da Lee and His Family", Folk Art Magazine, 47 (Winter 2004/2005). Pdf copy of article published with permission of the American Folk Art Museum. (The article is contained in a large pdf file and may take a while to load onto your computer. It has beautiful color photos and is worth the wait.)

Rumsford, Beatrix, American Folk Portraits Paintings and Drawings from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Boston: Little Brown, in association with Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (1981) p. 77-79.

1Biographical information and description of the Da Lee family work gleaned from Suzanne Rudnick Payne and Michael Payne, "To Please The Eye, Justus Da Lee and His Family", Folk Art Magazine, 47 (Winter 2004/2005).

Please view the Justus Dalee portrait currently in inventory on the Portraits pages

-

-

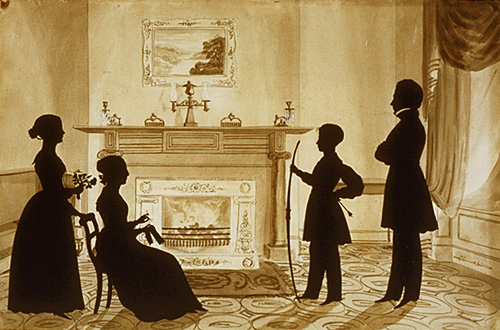

Joseph H. Davis (1811-1865) (active 1832-1837)

Approximately 160 watercolor folk portraits have been attributed to Joseph H. Davis since his work was identified in the 1930s. However, little was known about the artist until the biographical research done by Arthur and Sybil Kern. The Kerns confirmed the common speculation that the artist Davis was the man from Limington, Maine known as "Pine Hill Joe." Pine Hill Joe was remembered as "a farmer inclined to suddenly leave his farm to go wandering from town to town 'painting pictures of people on little sheets of paper.'"2

According to the Kerns, Joseph H. Davis was born on August 10, 1811 to Joseph and Phebe (née Small) Davis in Limington, Maine. He was 21 years old when the first of his known portraits was painted in 1832. Davis is known to have painted in the Lebanon-Berwick area of Maine and Dover-Somersworth area of New Hampshire. Many of his subjects had a connection with the Freewill Baptist Church, leading to supposition that Davis was connected with this church. Davis married Elizabeth Patterson on November 5, 1835. Five days after the marriage, the first of what was to become many land transactions was recorded in what was apparently Davis' new profession as a land trader.

Davis' most prolific years of painting appear to be 1835 to 1837, after which no dated paintings have been found. [The painting pictured here appears to negate the previous statement as the inscription on the verso of the frame dates it at 1838. However, the inscription does not appear to be contemporary with the painting and family history often includes errors.] He may have increased his production of paintings to support his new wife. Both the increase of his success as a land trader and the impending birth of his daughter in 1838 may have contributed to the end of his career as an artist in 1837. Perhaps he felt the need for less travel than was required by an itinerant artist and perhaps the land trading business paid him more handsomely than the art business in which he charged only $1.50 per portrait.3 After the last known portrait was painted in 1837, the Davises moved often, living in Massachusetts, Maine, and New Jersey. His success as a land trader is indicated by numerous recorded deeds. Joseph H. Davis' death is listed in the records of Woburn, Massachusetts as follows: "Davis, Joseph H., son of Joseph and Phebe (b. in Limington, Me.), of disease of liver. May 28, 1865, 53y.9m.18d."

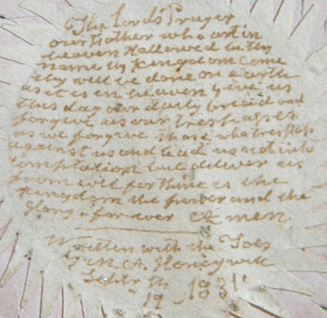

As an artist, the work of Joseph H. Davis stands out as a stunning example of the American Fancy Period of the 1830s even though his work is naïve and obviously self-taught. He depicts his sitters in profile, with their bodies slightly turned to reveal more of their clothing. Single figures generally face the right. Couples generally face each other, whether painted together or in two individual paintings. The great majority of his work depicts sitters in full length, although five half-length recorded portraits have been attributed to Davis. The trademark of Davis' work is his glorious use of color and pattern in the vibrant floorcloths or patterned floor decoration that he placed under most of his subjects' feet and the garishly grained or paint decorated tables and chairs he included in family portraits. These family or couples portraits portray a variety of personal accessories that are likely more symbolic than real. Davis often included the exterior of the couple's homestead in a painting that he placed on the background wall (which was usually elaborately swagged). Women often carried colorful patterned reticules or purses. Several portraits include a cat. Books symbolized the education of the family and the inclusion of a bible represented their faith. Davis' settings are based on an artificial formula that varied little from painting to painting. That said, they are fabulous examples of the exuberance of the American Fancy Period and were surely loved by their consignors because they depicted the sitters in the American middle-class dream parlors of the 1830s. The portraits and accoutrements were drawn on wove paper in pencil and then painted in with watercolor. Some of his work included an inscription across the bottom with the names of the sitters, sometimes their ages, birthdates, and hometown. As of 1992, only six signed works had been found. One of the six was signed "Joseph H. Davis/Left Hand/Painter."

References:

Anderson, Marna A Loving Likeness American Folk Portraits of the Nineteenth Century, (Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. (1992). 16-17.

D'Ambrosio, Paul S. and Emans, Charlotte M., Folk Art's Many Faces: Portraits in the New York State Historical Association, New York State Historical Ass'n, Cooperstown 1987. 58-64

Kern, Arthur B. and Kern, Sybil B., "Genealogy and Historical Research: "On the Importance of Genealogical Methodology in Researching Early New England Folk Portraitists", The Art of Family, Genealogical Artifacts in New England, Ed. D. Brenton Simons & Peter Benes, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston 2002. 254-59.

Rumsford, Beatrix, American Folk Portraits Paintings and Drawings from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Boston: Little Brown, in association with Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (1981). 83-87.

Savage, Gail & Norbert H., and Sparks, Esther, Three New England Watercolor Painters. Art Institute of Chicago, 1974. 22-41.

2Kern, supra at 97, (quoting Sinney, Frank O., Primitive Painters in America: An Anthology by Jean Lipman and Alice Winchester (New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1950).

3D'Ambrosio, supra at 59.

-

-

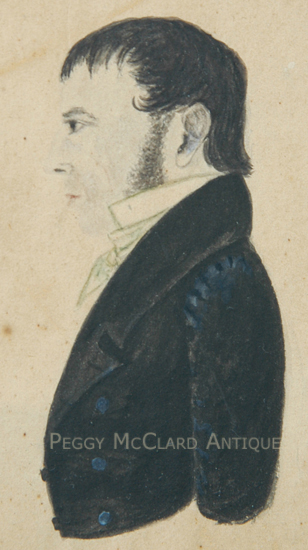

J.A. Davis (1821-1855)

When Jane Anthony Davis signed her work, it was as "J.A. Davis" and until research done by Arthur and Sybil Kern in 1981, she was thought to be a man, probably from Rhode Island or Connecticut. Through meticulous research and the discovery of family descendents, the Kerns learned that Jane Anthony was born in Rhode Island on September 24, 1821, married Edward Nelson Davis of Connecticut in 1841 and died in Rhode Island at the young age of 33 on April 28, 1855. Ms. Davis attended the Warren Ladies Seminary in Warren, Rhode Island for at least two terms in 1838. All of her known dated portraits were painted after her education at the Seminary. This suggests that the seventeen year old Jane may have begun painting seriously while attending the Seminary. From found dated portraits, Ms. Davis appears to have taken two breaks from her portrait painting: first the years 1840 to 1842--a hiatus probably attributed to Jane preparing for her wedding and then moving to Connecticut; second from 1844 to 1848--coinciding with Mr. and Ms. Davis moving back to Rhode Island and the birth of Jane's second child. The last dated portrait found was painted on April 28, 1855, just eight months prior to the death of Jane Anthony Davis. She is buried in Providence, Rhode Island at Swan Point Cemetery.

Davis typically drew the entire composition of her portraits in pencil prior to her thin application of watercolor which she used in a naive style. She painted faces with an opaque bluish-white watercolor and added detailed facial features with graphite. Davis' sitters are almost always costumed completely in black with color only being used to highlight the penciled facial figures and other objects in the composition. She favored a 4" x 5" format of thin paper for her work.

References:

Anderson, Marna A Loving Likeness American Folk Portraits of the Nineteenth Century, (Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. (1992). 14-15.

Kern, Arthur B. and Kern, Sybil B., "Genealogy and Historical Research: "On the Importance of Genealogical Methodology in Researching Early New England Folk Portraitists", The Art of Family, Genealogical Artifacts in New England, Ed. D. Brenton Simons & Peter Benes, New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston 2002. 248-54.

Rumsford, Beatrix, American Folk Portraits Paintings and Drawings from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Boston: Little Brown, in association with Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (1981). 79-82.

-

-

Augustus Day (active 1800 - at least 1845)

Augustus Day was a carver, gilder, portraitist and silhouettist. He advertised as a physiognotrace profilist in Charleston, South Carolina in 1804. Most of his work seems to have been done in Philadelphia where he advertised as carver and gilder (1800-1806, 1814-1821), looking glass maker (1823-1825), and painter (1829-1833). His hollow cut silhouettes are impressed with a stamped signature "DAY'S PATENT" and his painted silhouettes were hand signed "Day Fecit". His very desirable painted silhouettes were either black with soft painted hair tendrils and frilled ladies' collars painted with a soft grey-blue tone; or the more desirable olive-green and elaborately gilt embellished. His hollow cut silhouettes are more scarcely found than his painted profiles and, indeed, are some of the most rare of signed American silhouettes.

-

-

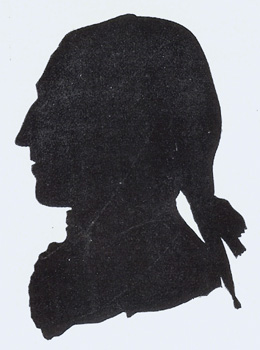

De Hart's silhouette of George Washington

Scan from Van Leer, Carrick,

Shades of Our Ancestors. Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1928. Plate after Page 18.

Sarah De Hart, American Silhouettist (1759-1832)

Sarah De Hart was one of the first American born silhouette artists and the earliest recorded American woman silhouettist. She was born on February 13, 1759 in Elizabethtown, NJ. (Although Charles Willson Peale is not known to have started cutting silhouettes until 1802, he was born 18 years earlier than De Hart, in Chestertown, MD in 1741.) De Hart’s earliest discovered silhouette was cut when she was twelve years old, in 1771. Unlike the majority of American silhouettists who would come later, De Hart cut her hollow cut silhouettes without the aid of the physiognotrace devices that were so popular in the 19th century. To date, no evidence has been discovered showing that De Hart cut silhouettes for profit, but she certainly captured the heart of George Washington for whom she cut several likenesses after visiting Mount Vernon with Washington’s sister Abigail Mayo in 1786. De Hart’s work is extremely rare (possibly because she only cut silhouettes for her own pleasure and the pleasure of friends and family). A group of about 130 of her works descended through her family until 1946 when the collection was sold to a collector. The collection was ultimately disbursed through auction in 1997.

-

-

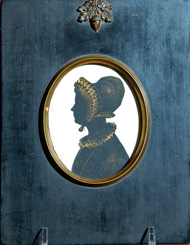

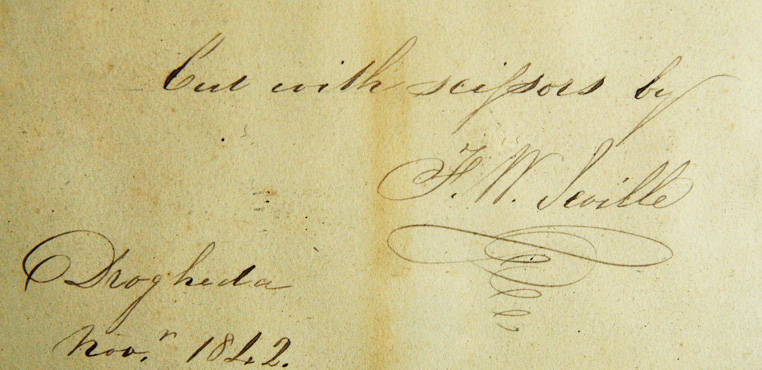

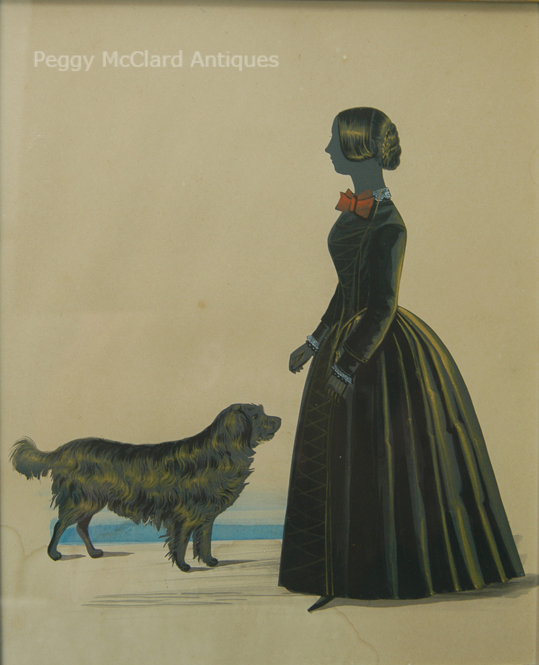

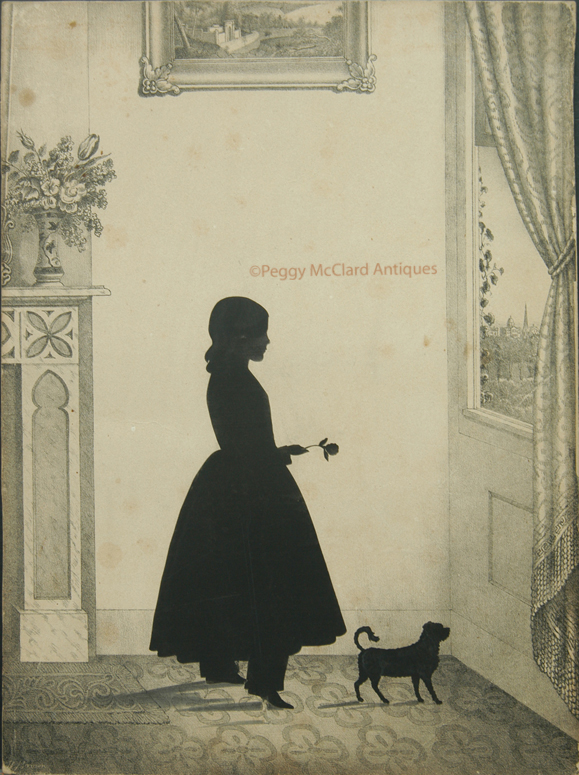

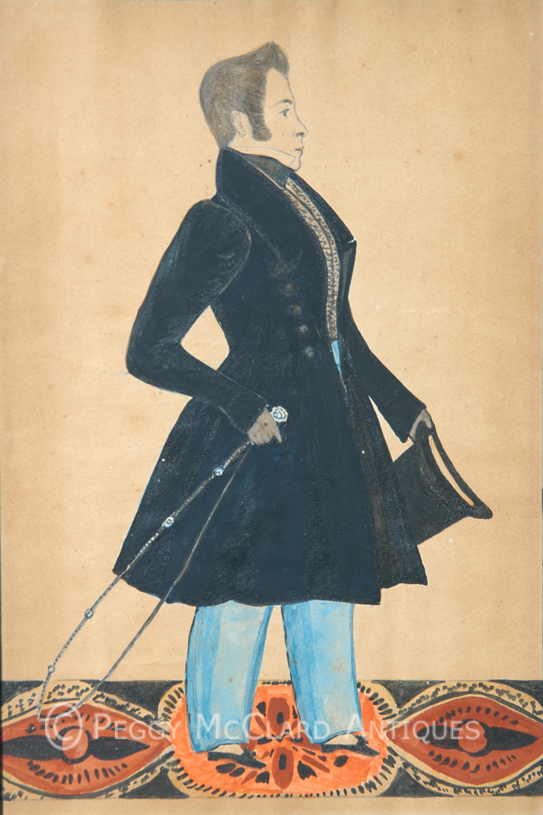

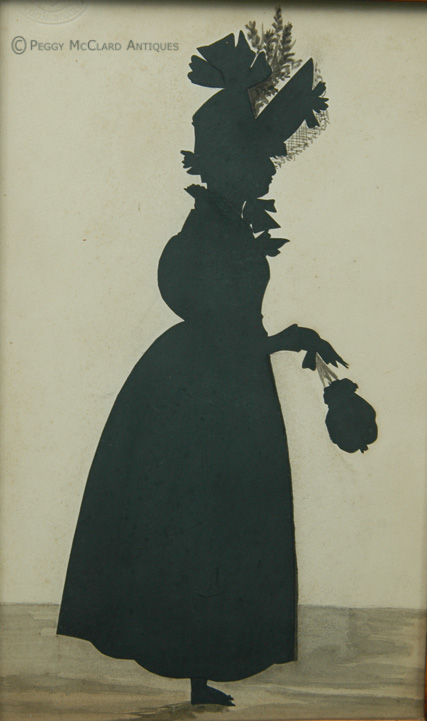

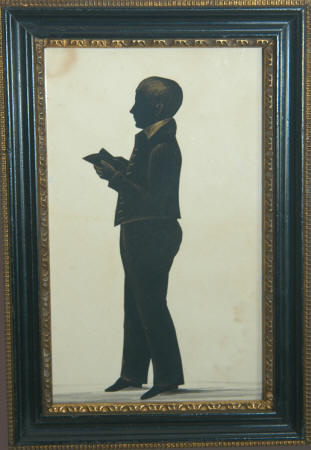

John Dempsey (active circa 1822-1844)

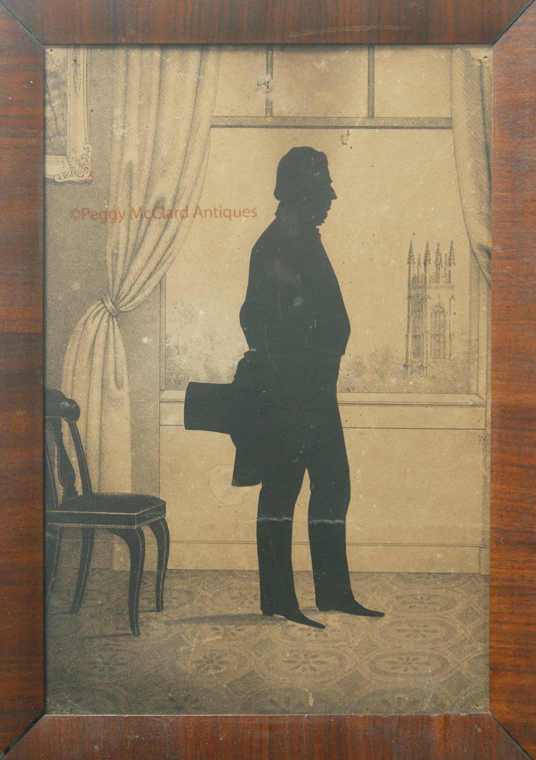

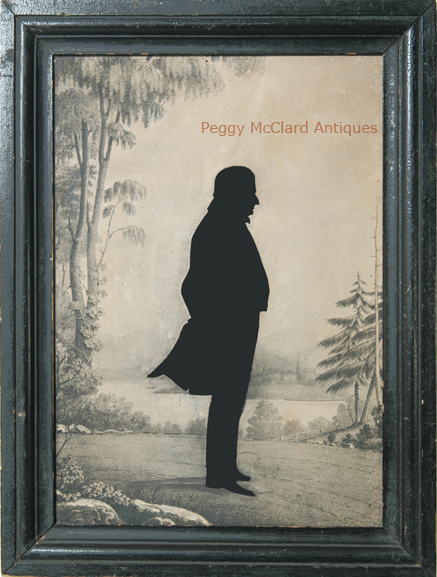

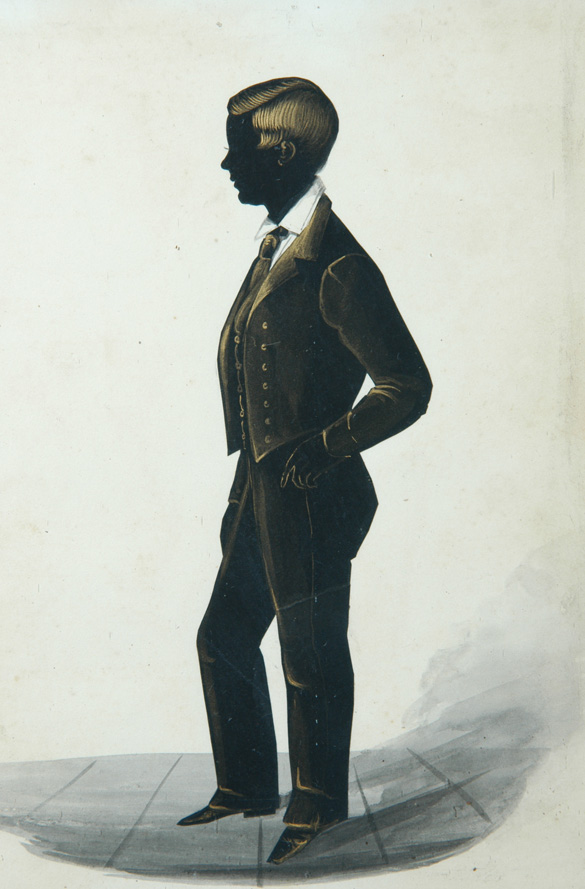

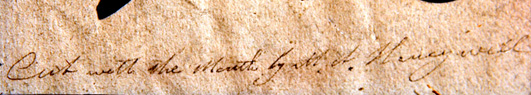

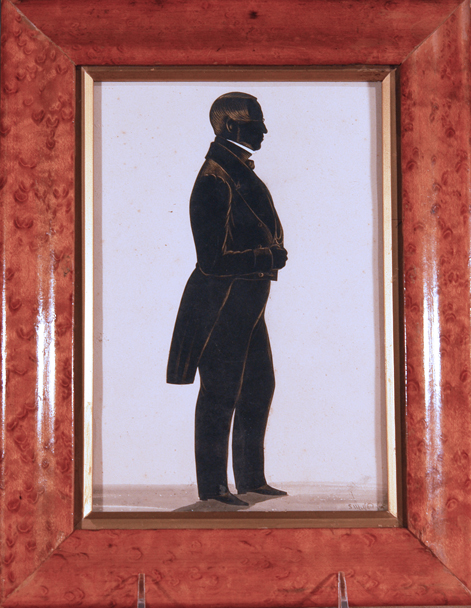

Little is known of John Dempsey's life. We know, through one of his advertisements, that he worked as an itinerant silhouettist beginning in the 1820s and that by 1840, he had cut silhouettes in England, Ireland and Scotland. He advertised that he took "Likenesses in Shade 3d./Bronzed 6d./Coloured Is. 6d and upwards. . . . ." He is best known for his full-length colored silhouettes, such as this one offered, in which his skill as an artist shines. McKechnie tells us "Dempsey's work in this field is so cleverly cut and pasted down that it is sometimes almost impossible to see the cut edge. The edge is concealed not by painting, but simply by skilled craftsmanship." McKechnie, Sue, British Silhouette Artists and their Work: 1760-1860. Sotheby Park Bernet, 1978 at 202. Indeed, this lady looks fully painted. The edges of the pasted paper are so skillfully painted that you almost need to remove the silhouette from the frame so that you can feel the raised edge. Dempsey kept a sample book showing his silhouette-making techniques. This was not a duplicate book, like Edouart, Bache or Chamberlain kept, but a book from which customers could pick the style of silhouette they preferred. The book included India ink painted bust profiles as well as full length painted profiles pasted to painted landscape backgrounds. Perhaps Dempsey's most important work is a large conversation silhouette titled, Liverpool Exchange showing eight-five figures upon a painted background showing the Exchange Buildings of Liverpool. Edouart apparently felt somewhat threatened by Dempsey's beautiful work. Edouart wrote that the use of color in silhouettes was "harlequinades" and he could not "understand how persons can have so bad and I may say, a childish taste!" August Edouart, A Treatise on Silhouette Likenesses, London, 1835. 24. It is generally understood among silhouette scholars that Edouart was referring to Dempsey's work. Edouart was always quick to lash out at those he felt most threatened by. Obviously, he felt threatened by Dempsey's beautiful work.

-

-

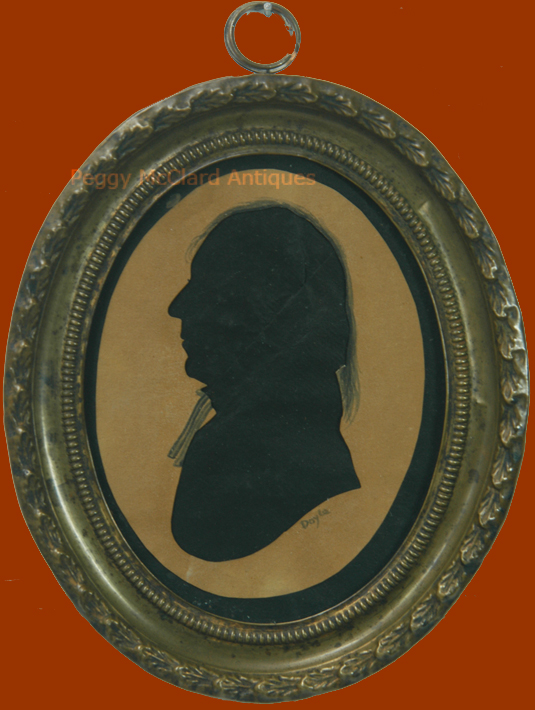

William M.S. Doyle, American Silhouettist (1769-1828)

William Massey Stroud Doyle was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1769. His father was a British soldier, but Doyle seems to have lived and worked his entire life in Boston. Doyle was a silhouettist, artist of portraits of both full-size and miniature. He worked in silhouette cutting, watercolor, oil and pastel. His silhouettes were beautifully rendered in hollow cut or paint (sometimes painted on plaster in the manner of Miers).

Doyle did not confine himself to his artistic endeavors. Indeed from 1806 until his death in 1828, Doyle, in partnership with Daniel Bowen, was one of the owners of the Columbian Museum. Together, the two men built a five story building in 1806 to house the museum. The five story building in 1806 towered over the surrounding landscape like a skyscraper! Unfortunately, the building burned to the ground in 1807, and the two men built a smaller building which they used for the museum until 1825.

In 1811, Doyle placed the following advertisement:

Wm. M.S. Doyle

Miniature and Profile Painter

TREMONT STREET, BOSTON, next House north of the Stone-Chapel, the late residence of R.G. AMORY esq. Continues to execute Likenesses in Miniature and Profiles of various sizes (the latter in shade or natural colors) in a style peculiarly striking and elegant, whereby the most forcible animation is obtained.

Some are finished on composition in the manner of the celebrated Miers of London.

Prices of Profiles—from 25 cents to 1, 2, & 5 dollars.

Miniatures—12, 15, 18 and 20 dollars.

Doyle’s silhouettes certainly live up to his salesmanship in that they are “peculiarly striking and elegant” and “the most forcible animation” truly is obtained. Rarely do they real ones come onto the market (although it is quite common to find 20th century fakes). What few there were (for Doyle did more portrait painting that silhouette cutting or painting) have all been snapped up into private collections and museums.

Please view the Doyle silhouettes currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

William M.S. Doyle, American Silhouettist (1769-1828)

William M.S. Doyle was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1769. His father was a British soldier, but Doyle seems to have lived and worked his entire life in Boston. Doyle was a silhouettist, artist of portraits of both full-size and miniature. He worked in silhouette cutting, watercolor, oil and pastel. His silhouettes were beautifully rendered in hollow cut or paint (sometimes painted on plaster in the manner of Miers).

Doyle did not confine himself to his artistic endeavors. Indeed from 1806 until his death in 1828, Doyle, in partnership with Daniel Bowen, was one of the owners of the Columbian Museum. Together, the two men built a five story building in 1806 to house the museum. The five story building in 1806 towered over the surrounding landscape like a skyscraper! Unfortunately, the building burned to the ground in 1807, and the two men built a smaller building which they used for the museum until 1825.

In 1811, Doyle placed the following advertisement:

Wm. M.S. Doyle

Miniature and Profile Painter

TREMONT STREET, BOSTON, next House north of the Stone-Chapel, the late residence of R.G. AMORY esq. Continues to execute Likenesses in Miniature and Profiles of various sizes (the latter in shade or natural colors) in a style peculiarly striking and elegant, whereby the most forcible animation is obtained.

Some are finished on composition in the manner of the celebrated Meirs of London.

Prices of Profiles—from 25 cents to 1, 2, & 5 dollars.

Miniatures—12, 15, 18 and 20 dollars.

Doyle’s silhouettes certainly live up to his salesmanship in that they are “peculiarly striking and elegant” and “the most forcible animation” truly is obtained. Rarely do they come onto the market. What few there were (for Doyle did more portrait painting that silhouette cutting or painting) have all been snapped up into private collections and museums.

In 1806, Henry Williams joined the business with Doyle and Bowen. Advertisements soon afterwards placed by Williams and Doyle announced “Miniature and Portrait Painters at the Museum: where profiles are correctly cut.” Doyle and Williams collaborated until at least 1815. Doyle became the sole proprietor of the Columbian Museum in 1808 and continued until his death.

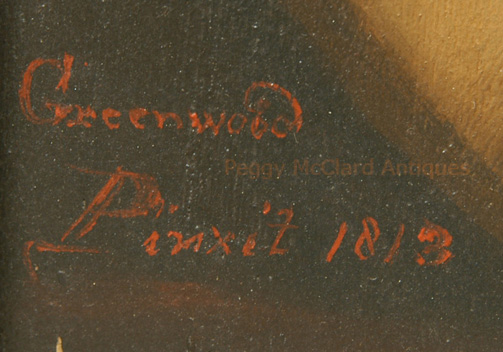

Doyle’s style in portrait miniatures varied considerably over time. It is said that Doyle greatly benefited from working with Williams on his painting skills. Fortunately, Doyle signed and dated many of his miniatures so that they can be identified despite his varied styles. His early work is characterized by strong use of line to draw the hair and facial features and distinctive diagonal striations in the background. Doyle’s later work shows paint applied in broad washes and shadows and folds emphasized with gum arabic. His subjects, usually male, are placed left of the center, facing right.

References:

Falk, Peter Hastings (ed.), Who Was Who in American Art 1564-1975. Sound View Press, 1999. 955.

Foskett, Daphne, Miniatures Dictionary and Guide. Antique Collectors Club, Suffolk, England, 1987. 531.

Johnson, Dale, American Portrait Miniatures In The Manney Collection. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 1990. 114 & Plates 76, 77.

Strickler, Susan E., American Portrait Miniatures The Worcestor Art Museum Collection. Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts, 1989. 52-54.

-

-

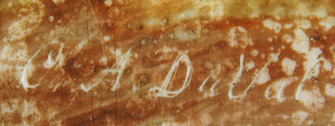

Charles Allen DuVal (1808-1872)

Charles Allen DuVal was born in Ireland in 1808 (see below for an update on his date and place of birth). He took up painting after a jaunt at sea. Around 1833, Duval moved to Manchester, England where he developed a large following for his paintings. In Miniatures Dictionary and Guide, Daphne Foskett called him a “witty writer” and I found evidence that Duval contributed articles for North of England Magazine and authored pamphlets about the American Revolutionary War. He exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1836-1872 and also in Manchester and Liverpool. Duval had a large audience for his paintings in London where he also worked and was said to be “a good artist.” He painted portraits, figure subjects, and portrait miniatures. He was an engraver and lithographer.

In 1865, Duval lent a miniature portrait to the South Kensington Museum for exhibit. The catalogue for that exhibit incorrectly recorded his name as Du Val – a mistake that is often repeated.

Duval’s work currently resides in the collections of the British Museum and the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Note--I received an email from DuVal's great-great-granddaughter who says she has a copy of a document in DuVal's own handwriting in which he gives his date of birth as 19th March 1810. She also tells me that although his parents were Irish and DuVal spent his early years in Ireland, in the censuses he gave his place of birth as Beaumaris, Anglesey, Wales. He resided in Manchester, England starting in his early twenties. Thanks so much to his descendent for the information!

See website Charles Allen Du Val His Life and Works for more information.

-

-

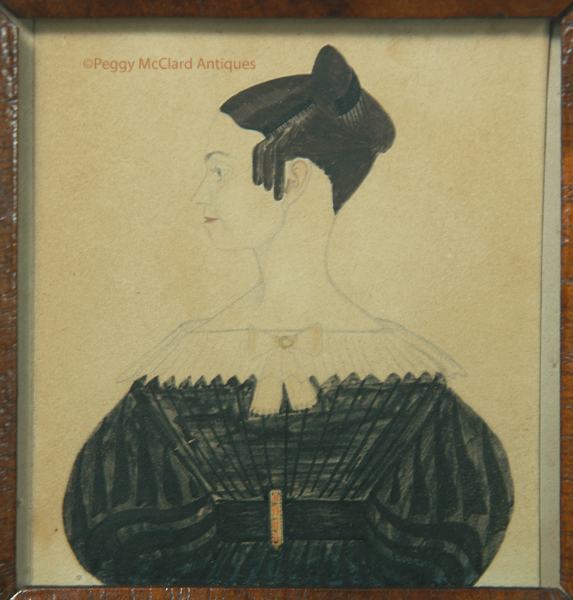

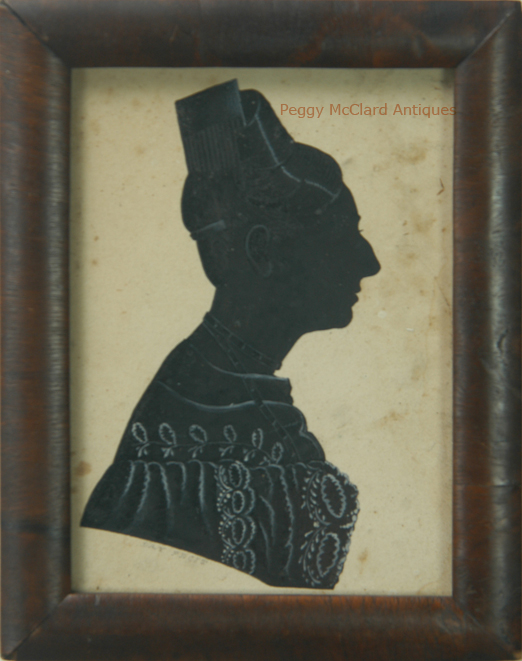

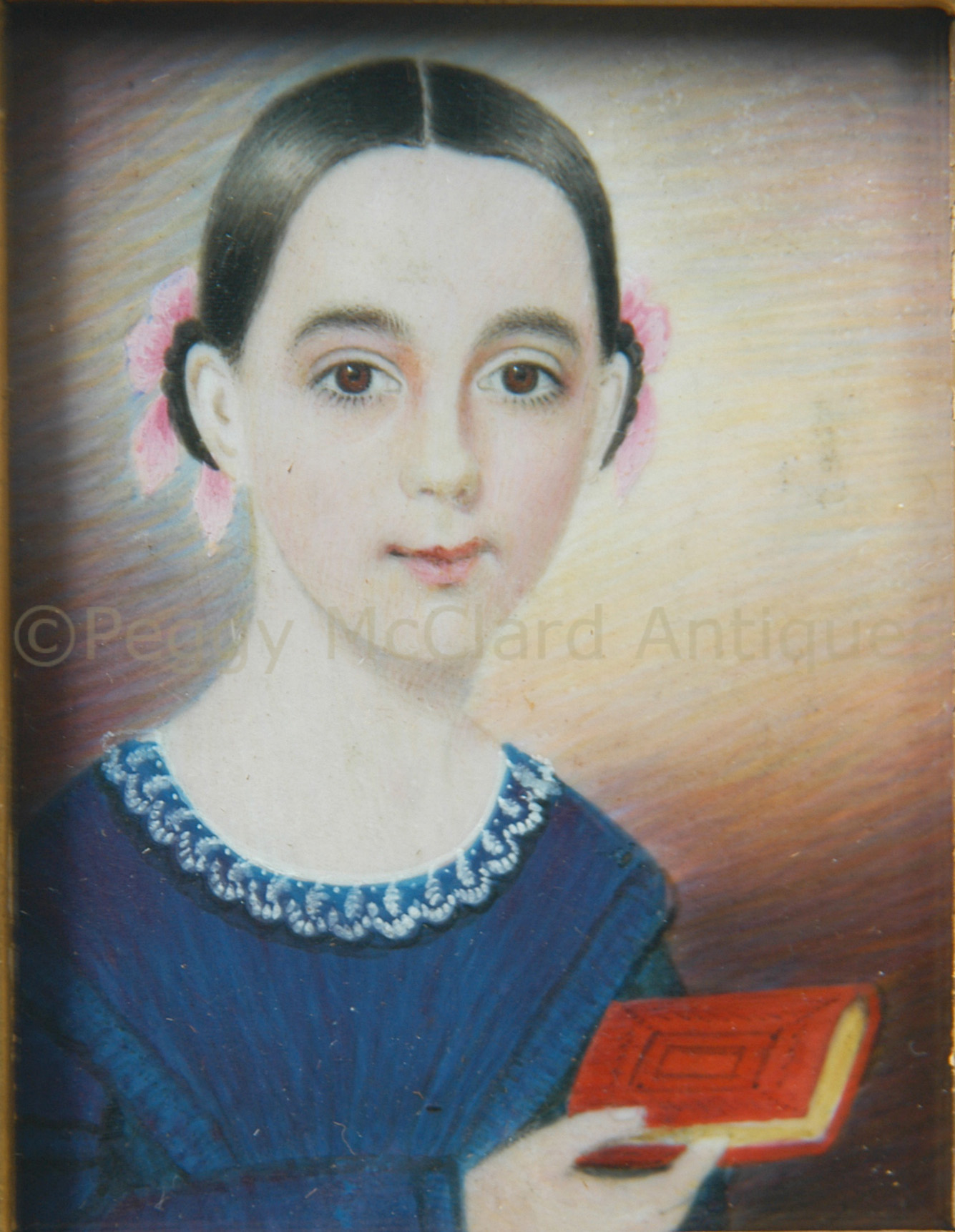

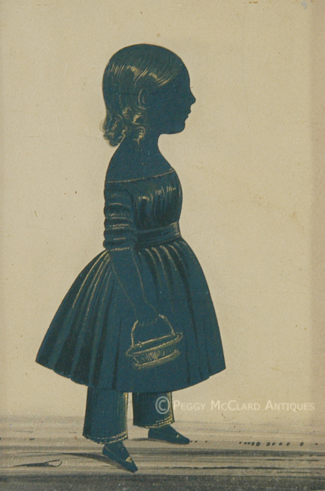

Emily Eastman (1804 -?) (active 1820s & 1830s)

Emily Eastman’s work represents the best of early 19th century American folk art. She worked in watercolors and graphite on paper or Bristol board. Her paintings are delightfully naïve, mostly representing stylishly dressed young women with carefully delineated details such as jewelry, lace, hair curls and hair adornments. It has long been thought that Eastman’s work was based on fashion plates of the time period, although no specific prints have been identified as the foundation for her work. Like so many folk artists of the period, Eastman rarely signed her work. Her paintings are attributed based on her use of pencil or thin watercolor to draw the outlines of her subjects which she then filled with washes of rich color. Precise lines form delicately and highly arched eyebrows, small bowed mouths, the outline of noses and tight hair curls. Eastman used sophisticated poses with bodies and heads slightly turned for an elegant effect. Her work is stylized, simple, highly decorative and shows a repetitive use of poses, formats, styles of dress, hair and facial features: all hallmarks of American folk art in which these repetitive or formulistic portraits were desirable and represented the sitters' social and economic standing. The ladies portrayed are, by all appearances, wealthy and would have had a strong social standing in their communities. There is one known portrait of a child attributed to Eastman. All other known pieces are of young women.

Emily Eastman was born in 1804 in Louden, New Hampshire. She married Dr. Daniel Baker in 1824. She was actively painting during the 1820s and 1830s. Virtually nothing else is currently known about her life.

Eastman’s work is included in collections of great museums across the country.

Emily Eastman Works in the Following Museum Collections (click the link for online images and/or information):

American Folk Art Museum:

Woman in Veil This portrait was a promised gift of Ralph Esermian. Because of his legal difficulties, I’m not sure whether the painting is still part of the museum collection, but an image is available at the link.

Boston Museum of Fine Arts:

Lady’s Coiffure with Flowers and Jewels

Lady’s Coiffure with Spray of Wheat and Wild Flowers

Young Girl Bedecked with Flowers

National Gallery of Art:

Curls and Ruffles (no online image available)

Smithsonian American Art Museum:

Woman with Roses in Hair (no online image)

Terra Foundation for American Art:

Young Woman with Flowers in her Hair

Please view the Eastman portrait currently in inventory on the Portraits pages

-

-

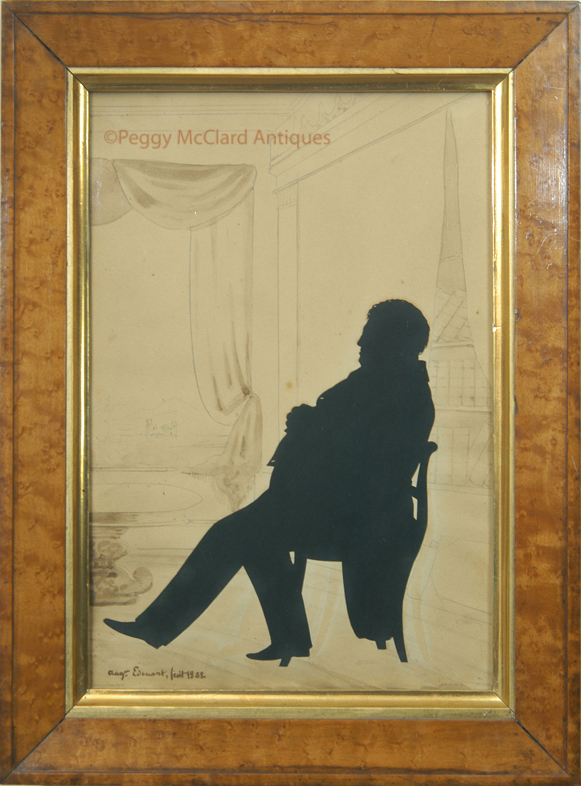

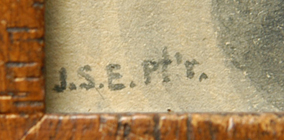

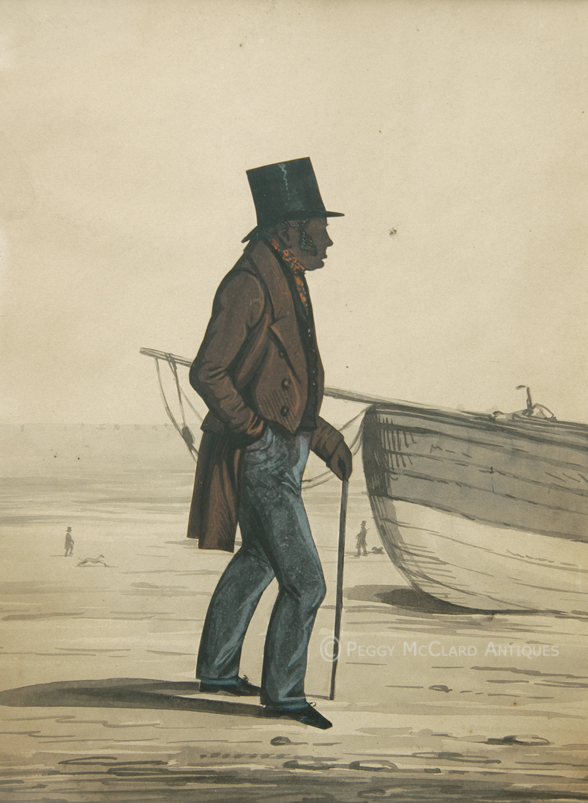

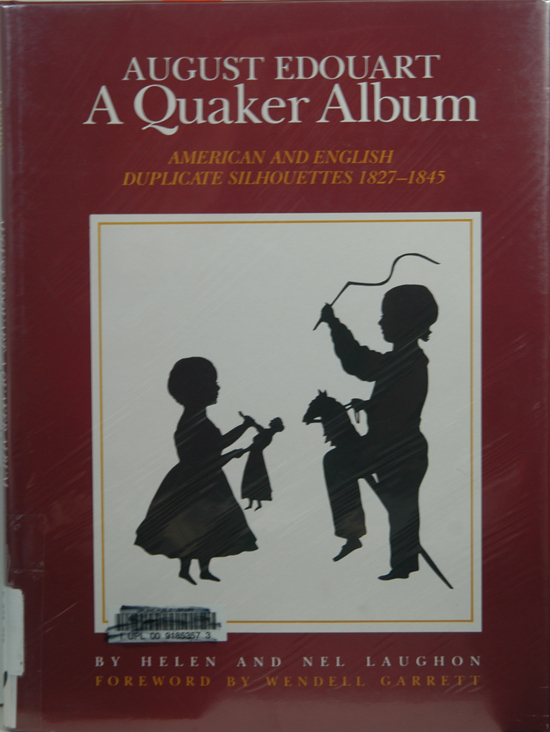

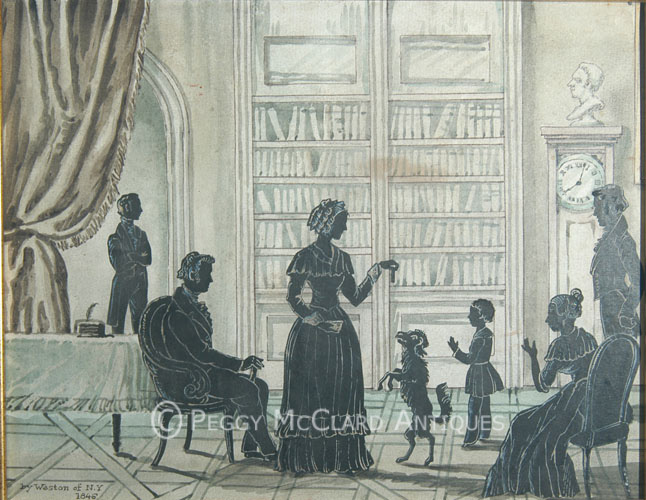

Augustin-Amant-Constan-Fidèle Edouart (1789-1861)

Edouart, born in the French harbour-town of Dunkerque, was a decorated member of Napoleon’s army. After the war, he was forced to move to England when he lost most of his property during the Evacuation of Holland. Like many French émigrés of that day, Edouart first tried to make a living teaching French. Finding too many rivals to excel as a teacher, this gifted artist turned his attention to hair art. Edouart made the intricate hair pictures that we are familiar with as mourning art, the plaited and floral ornaments which are commonly seen, and also wax portraits in which he embedded the natural hair to give a natural appearance. He excelled in the field of hair art in the same way as he would later exceed in silhouette cutting.

Edouart began silhouette cutting as the result of a heated argument with a friend who wished to commission a silhouette by an artist who used a mechanical contraption to cut profiles. In an effort to show that mechanics were inferior, Edouart sat the gentleman down, seized a pair of scissors from a nearby desk, blackened a quickly torn piece of paper with candle snuffers and snipped a silhouette of superior quality to that which the family had planned to commission. Edouart is said to have cut perfectly executed silhouettes in less than 2 minutes.

Edouart spent 24 years cutting what has been estimated as more than one hundred thousand silhouettes. He have believed that Edouart coined the term “silhouettist” because he was insulted by the then-common term “black-shade man.” By 1826, Edouart was cutting silhouettes exclusively of his hair work. He cut two original profiles of every sitting and kept one of each of the originals, named and dated, in his many folios. In 1835, Edouart wrote and published a book, A Treatise on Silhouette Likenesses.

Edouart traveled throughout England, continuously cutting silhouettes before first coming to America in 1839. He stayed in this country for ten years, cutting and cataloging silhouettes of the most important Americans of the time. Edouart cut silhouettes of six Presidents and ex-Presidents, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Supreme Court Chief Justice Joseph Story, and Madame Jumel who became the model for Charles Dickens’ mad Mrs. Havisham in Great Expectations to name a few.

In 1849, Edouart set out to return to England on the ill-fated ship, Oneida, which wrecked off the island of Guernsey. Although all of the passengers and crew were saved, only fourteen of Edouart’s folios were rescued. Broken-hearted by the loss of his life’s work, Edouart abandoned his profession and returned to France where he died at the age of 72. Edouart gave the rescued folios to the Lukis family, who had cared for him during the months following the shipwreck. There the folios stayed until, in 1911, Mrs. F. Nevill Jackson advertised to buy silhouettes for research she was conducting. The Lukis family sold the precious folios to her. Mrs. Jackson meticulously cataloged each silhouette. Where the background paper was waterlogged, she carefully removed the silhouettes and placed them on new background paper. Upon removal, she was delighted to find that Edouart had written the name of the sitter and date on the back of each silhouette as well as the bottom of each page. Mrs. Jackson cut keyholes into the new background paper so that Edouart’s written description could be seen. Where possible, she also cut his written descriptions from the bottom of the original folio pages and pasted them to the bottom of the new pages.

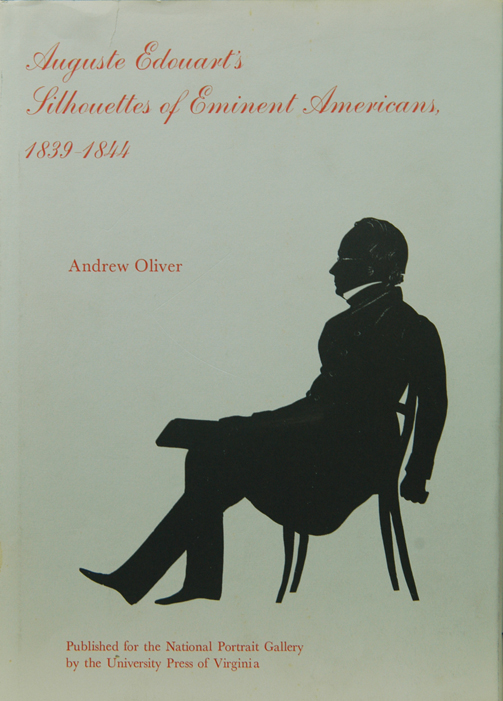

Mrs. Jackson eventually sold the six folios with American silhouettes to Arthur Vernay of New York. Mr. Vernay sold the majority of the American duplicates at a 3-week sale in 1913. One remaining unbroken American folio was kept by Mr. Vernay and made the subject of Auguste Edouart's Silhouettes of Eminent Americans, 1839-1844, by Andrew Oliver. Eight hundred sixty-two individual American duplicates were eventually sold to renown silhouette collector Reverend Glenn Tilley Morse.

Edouart is known for his simple and lifelike full-bodied silhouettes which are ripe with action. He used no colored embellishment, denouncing gilding, coral necklaces, and colored dresses as harlequinades. Although Edouart pronounced that “the representation of a shade can only be executed by an outline,” beginning in 1842, he sometimes penciled or chalked indications of hair, the lines of a coat, buttons and fingers. His ultimate surrender to the use of some embellishment was probably a nod to the overtaking of his profession by the daguerreotypists. However, he always refused to use bronzing or any other color in the embellishment of his figures.

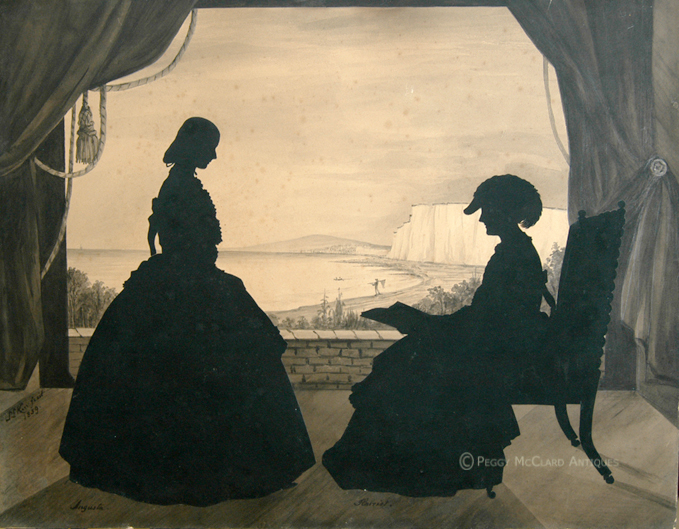

Edouart cut and assembled compositions of entire families, often backing them with stock lithographs of room or outdoor settings. Less common are his watercolor backgrounds in sepia tones. What is expected and delightfully delivered in the Edouart silhouettes are accessories such as hats, canes, letters--even family pets. His silhouette of Mrs. Mary Appleton depicts her cutting a silhouette herself. The tiny additional profile is said to be remarkably recognizable as Mrs. Appleton’s husband.

A new and exciting discovery recently surfaced from a Parisian bookseller: Edouart’s personal folio of “Scraps” in a book labeled “Animaux”. This is the most Edouart exciting discovery in a century! Mrs. Jackson discovered the duplicate folios in the first decade of the 20th century. It appears that Edouart took this scrapbook with him to Calais. It was filled with figures of dogs, horses, toys, mythical characters, floral sprays, and on and on. It looks like Edouart used the book to keep practice figures of unusual forms that he might have been commissioned to add to conversation silhouettes as well as figures that he cut for his own amusement and for his traveling exhibition. Animaux was a treasure trove of incredible pieces. I have been so lucky to acquire more than 200 figures removed from this book. In the coming months, I will be offering these mind-boggling silhouettes for sale. They will always be lightly mounted on acid-free materials and framed in period frames. The reverse of the mountings will always be stamped with a specially made stamp for items from this book and also with my collection stamp. The reason for my insistence on mounting and stamping is because these figures are so unusual (although distinctly from Edouart’s hand) that I want to help future generations authenticate them because they can be traced back to me.

The most complete information about Edouart can be found in the following reference books:

Jackson, E. Nevill, Silhouettes: A History and Dictionary of Artists, Peter Smith Publisher, Incorporated, 1979. Plate 14.

McKechnie, Sue, British Silhouette Artists and their Work: 1760-1860, P. Wilson for Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978 at plate 360, page 299.

I usually have a copy of both offered for sale on my Books

page.I am very pleased to be able to show you an Edouart silhouette, complete with watercolor, graphite and ink background as commissioned by the James R. Westcott family of Saratoga Springs alongside Edouart's duplicate silhouette of the Westcott family as taken from the rescued folios. You will notice that the commissioned silhouette (to the immediate left) includes (from left to right) daughter Marie, wife Mary, son James Gardner Westcott, and father James Randell Wescott. The duplicate (to the immediate right) includes Marie and Louisa (or Louise) P. Westcott, wife Mary and James R. Wescott. Remember that when Mrs. Jackson bought the rescued folios from the Lukis family, many of the silhouettes were missing from the pages as a result of their trip to the bottom of the bay. Apparently, James Gardner Westcott was one of the missing folio silhouettes. The commissioned silhouette of the Westcott family is dated 1840 and Marie, Mary and James R. are dated 1841 in the folio. I have absolutely no explanation for why the dates are different on the commissioned silhouette and the folio silhouettes. Louisa is dated 1843 in the folio and only she bears the faint chalk line embellishment that Edouart used starting in 1842. I surmise that Louisa was a member of James Randell Westcott's extended family who had her silhouette cut later. Edouart often went back in the folio to add a later-cut family member or add a notation about a death or marriage of a sitter. It would not have been unusual for him to have added Louisa to the Westcott family page later. We know she was placed on the same folio page as Marie before Mrs. Jackson restored the silhouettes because their names are written together on the inscription that Mrs. Jackson cut from the damaged folio page and pasted to the bottom of the later paper. Many thanks to the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec for granting permission to display a photo of the commissioned silhouette for this website.

Please view the Edouart silhouettes currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

Jacob Eichholtz (1776-1842)

Jacob Eichholtz was born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania November 2, 1776. He started his professional life as a coppersmith. He took painting lessons from Thomas Sully at least as early as 1808, but he was unable to devote himself to art until 1811. In 1812, he studied under Gilbert Stuart in Boston. Eichholtz was a regular exhibitor at the Society of Artists and the Pennsylvania Academy. Although he made occasional visits to Baltimore and Washington, Eichholtz lived and worked primarily in Lancaster and Philadelphia.

Eichholtz was recently the subject of an exhibition held concurrently at three institutions: the Lancaster County Historical Society (project headquarters), the Heritage Center Museum of Lancaster County (now the Lancaster Cultural History Museum), and the Phillips Museum of Art at Franklin & Marshall College. A catalog of that exhibition was written by Thomas R. Ryan.

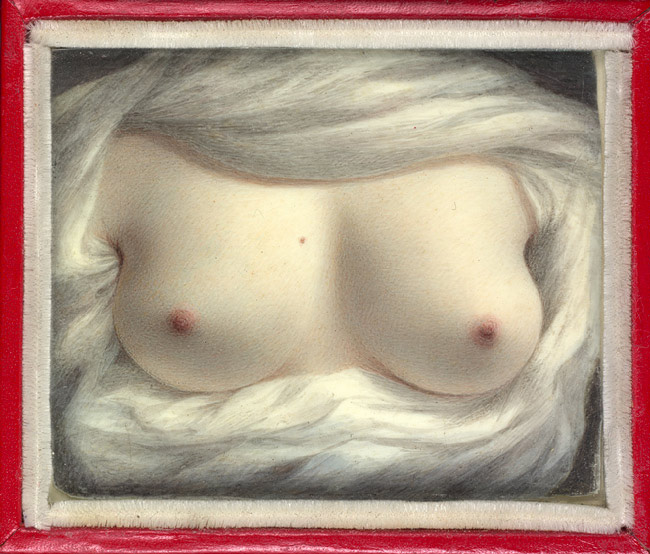

Eichholtz' wood panel portraits tended to be small, painted inside a faux oval and painted in profile. His canvas portraits tended to be larger, painted more academically with sitters facing the viewer. The small, wood panel portraits are favored by collectors of folk art who like the naïveté which he tends to exhibit less in his larger portraits. Only one Eichholtz-signed wood panel portrait is known to exist. All other known Eichholtz wood panel profile portraits are attributed on the basis of that one signed profile. Each sitter in Eichholtz' wood panel portraits is painted in profile, half length and without hands showing. His earliest wood panel profiles have a somber shaded background within an oval surround. By 1810, Eichholtz had pretty much discountinued the shaded backgrounds, instead using more monochromatic backgrounds painted in browns and black. The wood panels are always close to 7" x 9". Eichholtz is known to have painted these wood panel profiles from 1801 until about 1818.

References:

Rumford, Beatrix T. (ed.) American Folk Portraits Paintings and Drawings from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center. New York Graphic Society, 1981. 91-92.

Ryan, Thomas R. (ed.) The Worlds of Jacob Eichholtz, Portrait Painter of the Early Republic, Lancaster Country Historical Society, 2003.

-

-

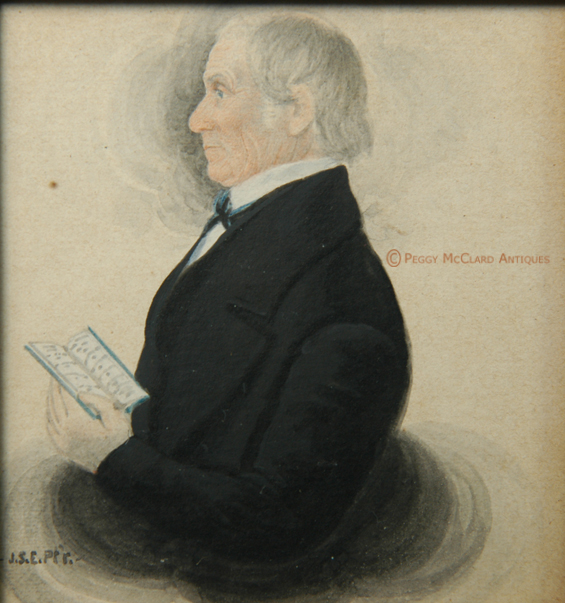

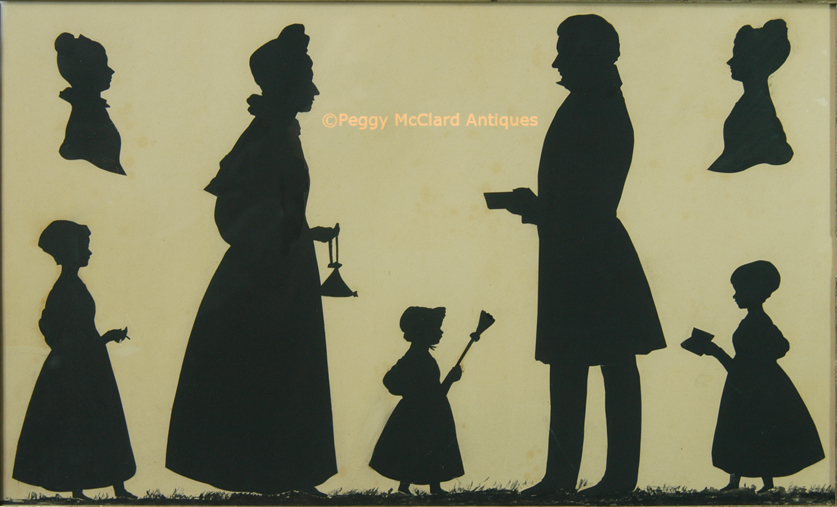

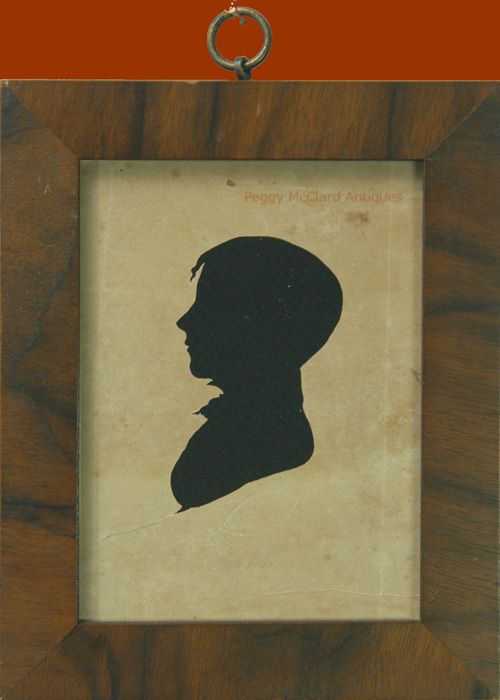

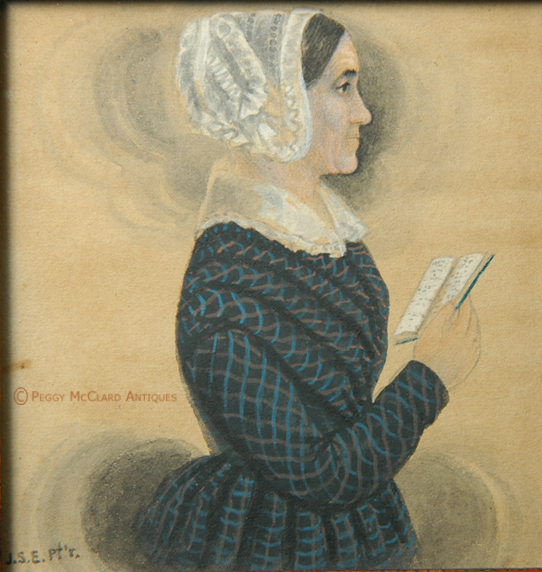

James Sanford Ellsworth (1802/03 - 1874)

James Ellsworth was born to John and Huldah Ellsworth somewhere in Connecticut in either 1802 or 1803. On May 23, 1830, Ellsworth married Mary Ann Driggs in Harford, Connecticut. The couple had a son (rather scandalously it must be presumed), William Leyard Ellsworth, on November 15, 1829. In 1831, James and Mary had a second son, Edward Ellsworth. In 1839, Mary Ann Driggs Ellsworth obtained a divorce from the painter, claiming James deserted the family in 1833.

James Ellsworth painted miniature watercolor folk portraits from about 1835 to 1855. He worked primarily in Connecticut and Massachusetts but is also known to have traveled to Pennsylvania and Ohio (where he complained to have been shot at by a mob who suspected him of being a Confederate). As of 1980, there were 263 known miniatures by Ellsworth and eight oil portraits. He is known for his remarkable talent for portraying the character of his sitters in their portraits. Faces are skillfully modeled. The color of eyes and shape of brows are expertly rendered. Likenesses are presumably very accurate as they are uncompromising so as to depict some of his sitters as plain, homely and even toothless. Hairstyles and dress document the actual country fashions of the period and places where he worked. Ellsworth had a problem depicting hands and so often hid them entirely or showed the hands folded or holding an object. Books, flowers, fans, handkerchiefs, birds are all props that can be found in his works. All but seven known Ellsworth miniatures are painted in profile. He depicted his figures with more negative space left behind the figure than in front.

Ellsworth's backgrounds produce a most clever device that one has come to expect from an Ellsworth miniature. His sitters are placed in front of cloverleaf clouds which wisp behind their heads and seem to support them in air. "His scalloped clouds support almost all of the sitters so that, though only some are chairborne, almost all are airborne." See Lipman at 71. The clouds give an illusion of depth. Men usually emerge from the support clouds at their waist while women rise from their hips. Some of his figures are seated in one of six basic patterns of chairs. The chairs are whimsical, unreal and never completely shown. They are all upholstered and have natural, stained or painted wood chairs. Ellsworth may have seen these chairs as his trademark because the majority of the portraits with chairs are left unsigned.

The usual size for his miniatures was 2 7/8" x 2 1/2" and painted on thin paper mounted to a heavier stock. He also did some larger miniatures, about 3 1/2" x 4 1/2". He painted a few miniatures on embossed paper or envelopes used for Valentines. He often framed his miniatures in a narrow, half-inch mahagoney veneer, fitted with blown glass, secured at the back with glazier's points and hung with a wire ring at the top of the frame. Ellsworth is known to have used 13 different whimsical signatures, including: "ELLSWORTH PAINTER"; " J.S. Ellsworth, Painter"; "J.S.E. Ptr."; "J.S.E. Pr."; "J.S. Ellsworth, Portrait Painter"; "Ja. S. Ellsworth, Portrait Painter"; "James S. Ellsworth, Painter"; "James S. Ellsworth, portrait painter" with a flourish beneath; "J.S. Ellsworth, px."; "J.S. Ellsworth, pinx"; "James Sanford Ellsworth", "Sanford Ellsworth", and "J.S. Ellsworth, del.".

Exhibits: "The Paintings of James Sanford Ellsworth, Itinerant Folk Artist 1802-1873", Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection, October 13 - December 1, 1974.

References:

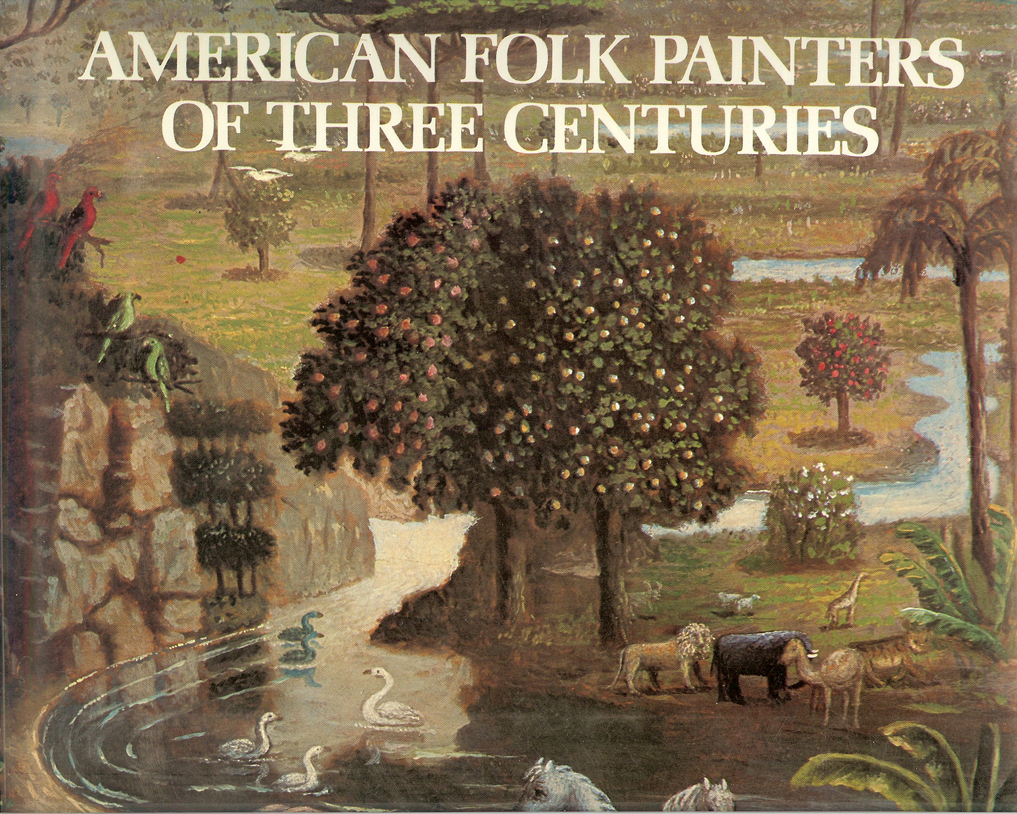

Lipman, Jean & Armstrong, Tom, eds., American Folk Painters of Three Centuries. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, 1980. 70-73.

Mitchell, Lucy B., The Paintings of James S. Ellsworth, Itinerant Folk Artist 1802-1873, Exhibition Catalog. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation 1974.

Rumford, Beatrix T. (ed.) American Folk Portraits Paintings and Drawings from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center. New York Graphic Society, 1981. 92-93.

-

-

John Field (1772-1848)

Much of his career was spent working for John Miers Studio. Please see the entry for Miers below.

Please view the Field silhouettes currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

Edward Foster (1762-1864)

Edward Foster was born November 8, 1762, two years into the reign of the monarch who would become his most important, George III. Foster's father was a gentleman land-steward and mother was the child of nobility. He joined the Derbyshire militia at the age of 17 and remained in the military for 25 years. Once Foster retired from the military at age 42, he turned his attention to his artistic talents where he earned a fine reputation as a painter of miniatures and profiles. King George III appointed Foster the "Official Miniature Painter to the Royal Family" and moved him into lavish apartments in the Round Tower of Windsor Palace. Foster set up his business as a professional silhouettist in London around 1811 on The Strand. It was around the year 1811 that Foster began using papier mâché frames with a special brass hanger bearing his name above the Royal crown, meaning his appointment as Offical Miniature Painter must have been made by at least this date. In addition to working from his studio, Foster traveled as an itinerant artist. It appears that Foster returned to Derby in about 1832, during which year he was seventy-two years old. Never one to rest on his laurels, Foster began drawing and printing educational maps and charts for school use. He was married five times and had at least 17 children, only one of whom survived his death at 102 years old in 1864.

Foster's silhouette profiles were fully painted (not cut). His work is generally categorized as two types: "black profiles" with which he appears to have launched his career and later "red profiles." For his black profiles, he used thin black paint with detail added with pigment added to gum arabic and, sometimes, Chinese white. His "red profiles" are created with Venetian red and reddish-brown to which he added touches of gold and Chinese white. He used a three-dot technique to depict the transparency of the fabrics of women's dresses. Neck and shirt frills were generally left without color.

Peter Seddon, Derbyshire Life Magazine, July 2009 at 170-173.

Also see a great article about Edward Foster by Brett Payne at Photo Sleuth-blog

-

-

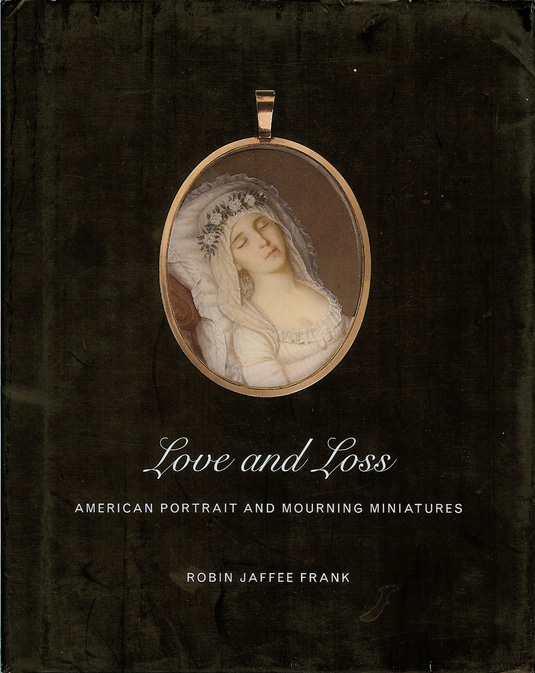

Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures

I've read this book cover to cover, several times. I find it fascinating and thorough in its information about portrait miniatures and mourning miniatures in America. The book is only 7" x 5" in outside dimensions but is packed with 376 pages of text and 189 illustrations (166 of them in glorious color). The text is well-written and authoritative and the color images are plentiful, beautiful and of great use for comparisons. This is a wonderful reference book and a fun read. Excellent copy with with just a bit of bumps to the dust cover (you can really barely see). Like new condition.

(#5231) $50

-

-

F. & H.A. Frith (after 1837-1854)

These brothers worked for much of their career as the Royal Victoria Gallery. Please see Royal Victoria Gallery below for information about the Frith Brothers.

Please view the Frith silhouette currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

John Gapp (active 1823-1839)

The Royal Suspension Pier (aka The Royal Chain Pier) was the first major pier built in Brighton, England. When built in 1823, it was intended as a landing stage for incoming ships. But Brighton provided a variety of amusements to draw tourists and the spaces between the cast-iron towers from which the chains were suspended soon attached profilists to set up shop in order to provide tourists with a memento of their visit to Brighton. John Gapp set up at the Third Tower in 1828 or earlier and seemed to have an ongoing rivalry with another silhouettist, Edward Haines, who had a similar style and had a gallery in the First Tower.

Gapp’s trade labels announce that he produced “likenesses from the scissors only” and that he captured “the expression and peculiarity of character are brought into action in a very superior style.” By 1830, Gapp’s trade label proclaimed “that he has no connexion with any other Person”. This is the first notice of his rivalry with Haines. Gapp’s price list is given as follows:

- Full-length Likeness 2s 6d. each

- Two Full-length Likenesses 4s. 0d. for two

- Likeness in Bronze 4s. 0d.

- Profile to the Bust 1s. 0d.

- Two of the same as above 1s. 6d.

- Ladies and Gentlemen on Horseback 7s. 6d.

- Single Horses 5s. 0d

- Dogs 1s. 6d.