Just for Fun

Why Collect Likenesses?

Why do we collect silhouettes and portraits of the 18th and 19th centuries? We have all heard people whisper about why anyone would want “dead people” decorating their homes. I’ve even been told that having likenesses of someone other than family is like “hanging somebody else’s dirty underwear on the wall.” Some people collect portraits and silhouettes to achieve the right “look” in their home displaying antiques of a certain period. But why do we go to museums to look at old portraits? What is the draw? Why are antique likenesses important to us now?

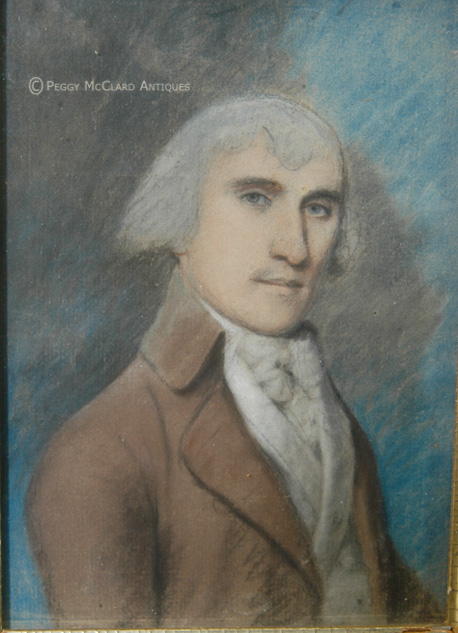

Portraits and silhouettes tell us so much about our past. By “our past”, I mean the formation of our country and of our civilization in general. We not only are able to enjoy something that pleases our eyes, but we can learn how the people depicted lived by appreciating their likenesses. We see how people dressed in certain periods. Although we can learn what items people lived with through written letters, inventories and wills, we can see how they lived with those items through their likenesses. It is true that many limners used fantasy clothing for their 18th century clients to give them a “timeless” look. Also, many portrait artists and silhouettists used a formula for painting backgrounds. However, even these formulistic backgrounds and clothing give us an idea of the goal that 18th and 19th century clients were striving for. The aristocrats of the 18th century wanted to look like "aristocrats" by being painted in “timeless” clothing that depicted luxurious silks that most people could not afford.

For example, the lady at the left is from an aristocratic family in Virginia. Her portrait was painted, circa 1725, in a classic British pose. In 1725, colonists considered themselves British and followed British styling in clothing, decorating their homes, and having their portraits painted.

The middle class of the 1830s wanted to be depicted in interior rooms painted in the best “American Fancy” tradition. A fabulous example of limners who painted by formula to give individual and family portraits the American Fancy look is J.H. Davis, who painted the portrait of Joseph R. Moulton in his wedding suit, circa 1835. His portrait is pictured to the right.

The conversation silhouette by William D. Beaumont, to the left, gives us an idea of how the middle class decorated their homes in the 1840s. It also shows us how women passed their time. The young seated woman holds an open book as she reads to her mother and sister. The mother wears glasses as she sits next to her open sewing box and works on colored embroidery in her lap.

Sometimes we can identify where the likeness was taken by the furniture depicted in the portrait. For example, the man to the left sits in what is known as a "Baltimore Chair". The man may not be in Baltimore, but we have a good clue that he is in the South, near Maryland. Also, the book in his hand shows us that he wanted to be depicted as an educated man. The gold key stick pin in his shirt front, the long gold watch chain attaching a watch that is in his coat pocket and the gold and coral wax seal hanging from that watch chain all show that he has some wealth.

While we don't know the identity of the sitters in the silhouette to the right, it is interesting to note that in 1830 King Charles X of Bourbon, one time king of France, his family and court took up exile to Holyrood Palace. Edouart cut the silhouettes of King Charles and many of the exiled members of his family and court at Holyrood Palace. The fact that the standing lady is holding a sketch of the Palace may be a clue that these ladies are from the Bourbon Court.

For the most part and especially in the Colonies, children in the 17th and 18th centuries were treated like miniature adults. There wasn't much time for play for anyone except the aristocrats. Many children didn't live to adulthood and parents did not coddle them for fear that growing too close to the child would make it even harder in the event that the child died at a young age. Even aristocratic children, like the French young boy to the left, were depicted in somber, stiff poses as adults would have been depicted. Notice the boy has his left hand partially inserted into his shirt front. This is a very adult male pose that was often used in the 18th century. This young boy does hold a toy whip, but it is a miniature version of the type of prop that an adult man would be depicted holding.

The young 18th century girl before is dressed much like a woman from 1760 would be.

By the early decades of the 19th century, adult attitudes had changed and children were cherished and allowed to be what they were--children. Families became closer. Toys were given to children and they were allowed to play. The baby at the right holds a popular coral bells rattle, make of coral (to ward away evil) and silver.

Note the playfulness of the White Family depicted by Edouart, to the left. Every child has a toy, a book or a pet. Starting on the left, the baby holds a coral bells, the toddler (probably a boy) holds a raised whip, the girl holds a basket of flowers and a doll, the tallest boy has a bow and arrow, the next boy has pet bird perched on his finger, and the oldest girl reads from a book to her father.

Likenesses teach us about the fashions of our ancestors. While Abigail Adams' letters poetically described the 18th century frizzled wigs that women wore, it is hard to imagine what they looked like without the visual aid of a portrait likeness. Our current beliefs that American colonists were all very Puritanical is belied by viewing portraits showing extremely very low necklines with lace tuckers covering the bust. Sometimes, as in this portrait, the bust was covered by a white or lace tucker that fit into the neckline, but sometimes it wasn't.

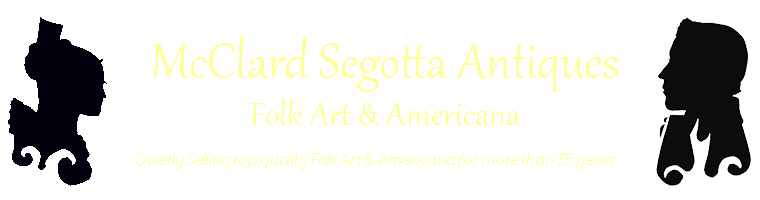

Since elementary school, we have known that men of the 18th century wore powdered wigs, but it is through antique likenesses that we can actually visualize those wigs. We also have a chance to see high collars with low lapels on coats, double-breasted weskits, and tied stocks on 18th century men. Written descriptions just aren't the same as seeing a likeness.

We can read Jane Austen's wonderful descriptions of women's clothing and hairstyles at the turn from the 18th to the 19th centuries. But, we can look to portraits and silhouettes to actually understand the impact of the feathered hats, the curls, the low cut dresses with Grecian influences in women's clothes.

The best way we can appreciate the loose hair knots at the back of the head with loose curls (often added hair), the ruffed necks and the empire waistlines of the 1810s & 1820s is through likenesses.

How could we envision the see the impossibly tall Apollo knots held with large tortoise shell combs of the late 1820s and into the 1830s without period likenesses. If you read a description of an Apollo knot, can you really imagine how absurdly high they really were? And then you would have to imagine the fur stoles or boas, long drop earrings, multiple strand necklaces, long watch chains tucked into a sash or belt, wide necklines, tiny waists, and huge padded sleeves of the 1830s.

And sometimes likenesses give us a glimpse into what the artist must have seen as hilarity in the latest fashions.

Likenesses show us how extremely young some boys were when they apprenticed out. This very young boy to the right is dressed as a mariner so we must believe that he went to sea at a very early age.

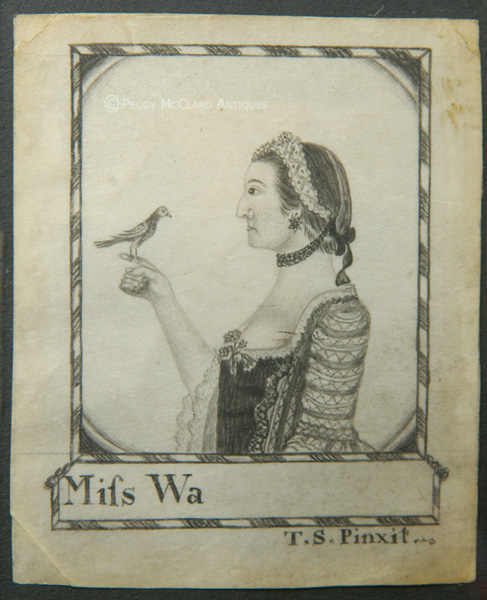

Small portrait miniatures were often carried or worn by people who were apart from their loved ones for work or military service. These tiny likenesses remind us how achingly hard it is to be away from our loved ones. The gentleman at the left must have been a naval officer leaving for a sea voyage when he had this portrait painted for his loved one. The back depicts the allegorical figure of "Hope" watching over a ship sailing out to sea.

Likenesses open our ancestors most intimate moments for us to see like the woman below with her dog in her lap and puppies in a basket in the background

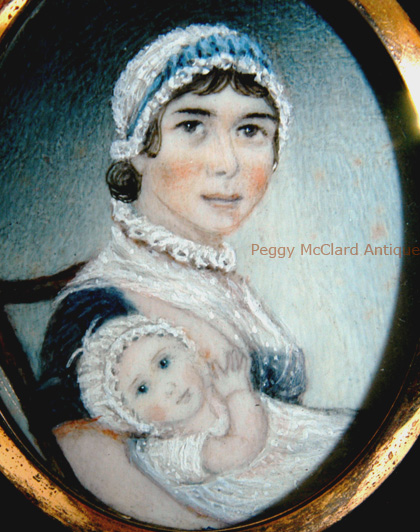

.....or this woman nursing her baby.

Likenesses remind us how important family is.

And what religious symbols mean to some of us.

We decorate our homes with portraits and silhouettes because they are beautiful, or funny, or folky, or give our home the look we are seeking. We appreciate, love and study these antique likenesses because they offer a glimpse into the formation of our civilization and our families. They open a door to see how our fashions, hobbies, home decorations, and family lives evolved. Whether folk art, academic, impressionistic, or whatever style we encounter, we can learn as much from likenesses and we do from written words.