Silhouettist Bios

-

Edgar Adolphe (circa 1807-at least 1879)

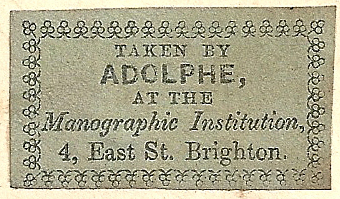

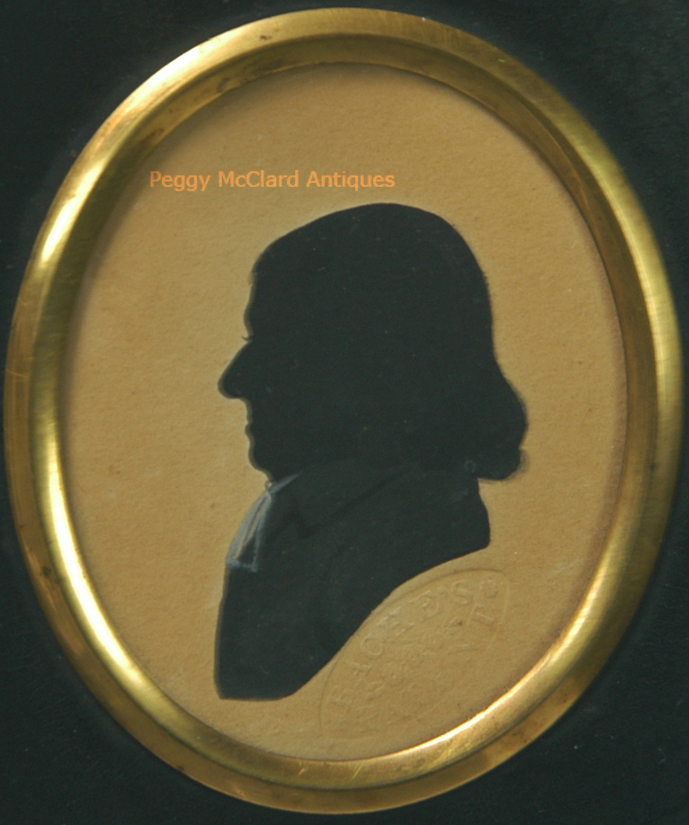

Most of what we know about Adolphe comes from his trade labels and profiles. Many of his trade labels refer to him as a a miniature and profile painter. A few full color portrait miniatures are known but most of his work seems to have been silhouettes. The earliest recorded work by him appears to have been done in 1832 and has a trade label proclaiming Adolphe as "Miniature Painter and Profilist to Louis Philippe, Kind of the French." Louis Philippe was King of France from 1830-1848. Since Adolphe appears to have left France for England by 1832 or earlier, Adolphe must have gotten his appointment as artist to the Court fairly soon after the Louis Philippe's accession. It is thought that Adolphe spent some time traveling and painting through England before he settled in Brighton no later than 1838.

In British Silhouette Artists and their Work, McKechnie indicates that Adolphe probably worked in Brighton through the end of his career. He may have, but, if so, he must have changed careers because I found that he married Margaret Phibbs in 1856 in Dublin and still lived in Dublin without his wife in 1879. Since he was only about 50 years old in 1856, he must have still be working at some profession, even if not as an artist. Interestingly, I also found that Adolphe served 3 weeks in jail for libel in 1840 in Sussex.

A previously unrecorded trade label on the back of a circa 1840 silhouette gives the address 4, East St., Brighton, which was the last address that McKechnie found for him. According to McKechnie's book, Adolphe was listed in a business directory showing the East Street address, which was a tobacconist's shop that was managed by his first wife, Eloise. The trade label that I found states that, at 4, East St., Adolphe was working at the Manographic Institute. I have been unable to find any information about the Manographic Institute or of Adolphe's first wife, Eloise.

-

-

William Bache, American Silhouettist (1771-1845)

William Bache was born in Worcestershire, England but hurried to Philadelphia at the age of 22 years. He became established as a silhouettist almost as soon as he arrived and, later, traveled to the Southern States and West Indies to ply his trade as an itinerant artist. Bache and his partners, Augustus Day and Isaac Todd patented a physiognotrace in Baltimore in 1803. (See information about Day & Todd below.) Bache advertised "Cutting, shading and painting of profile likenesses in a new and elegant style from long experience and great success in business and aided by an improved Physiognotrace, feels confident of rendering general satisfaction." Bache surely delivered great satisfaction with his elegant hollow cut silhouettes, cut assuredly and made elegant with added India ink curls on the border of the cutting and Chinese white highlights added to the background paper. He referred to these stunning silhouettes as "shaded profiles." Bache also showed his artistic expertise with fully painted profiles, many which were reproduced in the 1920s and are now being offered as period silhouettes. We know through his scrapbook which descended through his family that he also cut many cut & paste silhouettes, although some naysayers believe that the silhouettes in Bache's duplicate books are "hole-in-the-donut" silhouettes (the middle "waste" of a hollow-cut silhouette). Scholars have basically debunked the hole-in-the-donut silhouette as mislabeled. Whether or not you believe that it is possible to cut a perfect hollow-cut silhouette and have a perfect image left afterwards without any trace of a scissor entry, the fact is that if a silhouette is cut as a positive image and pasted onto a background paper, it is a cut & paste silhouette. Part of Bache's scrapbook can be seen at the National Portrait Gallery's blog facetoface. The National Portrait Gallery acquired the books, which hold 1,846 images, numbered below each profile and the back of the book contains a partial index of sitters, identified by the numbers placed under the profile. I have also owned one of Bache's cut & paste silhouettes, on the reverse of a painted silhouette. The cut & paste was of the same figure on the obverse of the background card. Bache added his impressed stamp from the painted side, after he had pasted down the figure on the reverse. The impressed stamp is partially through the actual cut figure, showing in reverse.

In his short career, Bache cut or painted profiles of George and Martha Washington as well as Martha's daughter Mrs. Lawrence Lewis (née Nelly Cutis), Thomas Jefferson and Daniel Wadsworth, among others. Bache's career was cut short when, sometime between 1812 and 1822, a tree fell on him while chopping wood. As a result, Bache's right arm was amputated. Bache was appointed postmaster of Wellsboro, Pennsylvania and remained in that position until his death in 1845.

References:

Christman, Margaret C.S., Herein Hang a Tale, The Bache Silhouette Book", facetoface, National Portrait Gallery Smithsonian Institute, August 13, 2008.

Fallon, Rosemary & Lockshin, Nora, "Which Cracked First: The Inkin' or the Egg? Analysis and Treatment of Ink Deterioration in the William Bache Silhouette Album", The Book and Paper Group Annual 27 (2008), 123-24.

-

-

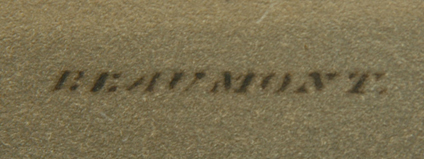

William Dyce (or Dyer) Beaumont (active c. 1833-1850)

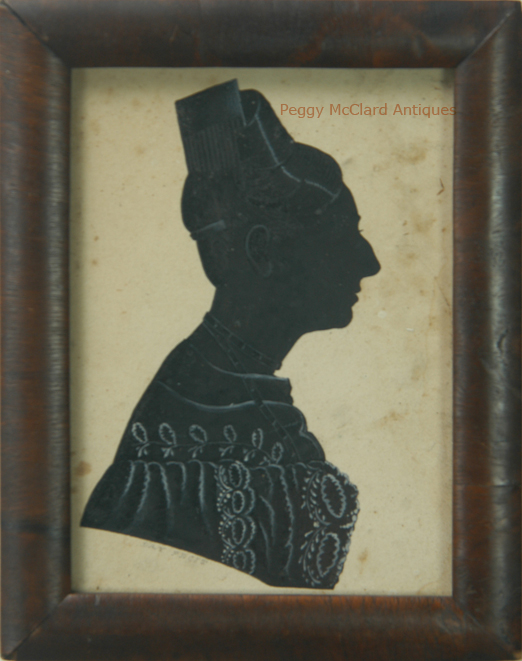

Beaumont's work is known for his use of sepia or dark brown paper from which he cut elegant and graceful women which he accented with subtle but highly unusual touches of color. Beaumont is known to have worked since the 1830s although his early work is not as successful as his later work. He cut men as well as women, but it is his women which are the most highly sought. His women were well placed with chairs of the early Victorian period and accessories such as ornate tea tables, stools, books, morocco-bound leather books, music scores, and sewing. Carpets are sometimes shown in color but to date we have no record of further painted backgrounds. His silhouettes of the 1840s and beyond has been called "among the finest of the period." McKechnie, Sue, British Silhouette Artists and their Work: 1760-1860 (Sotheby Park Bernet Publications, 1978) 190. Woodiwiss said, "Beaumont enjoyed using colour and always did so with the blending and discrimation of good taste. He arranged the details of his grouping with infinite care and his silhouettes may fairly be described as perfect examples of Victorian calm and breeding." Woodiwiss, John, British Silhouettes (Country Life Limited 1965) 68. According to McKechine is known to have signed his silhouettes "Beaumont", "W.H. Beaumont", W.H. Beaumont, fecit [date]." See McKechnie at page 190. In 2005, Diane Joll of the Silhouette Collectors Club reported that Christies sold Beaumont silhouettes signed, "W.D. Beaumont" and "Dyce Beaumont" so we all assumed that McKechnie was mistaken in saying that Beaumont signed with "H." Recently, a pair of silhouettes sold on ebay with the signatures "W. Dyer Beaumont, fecit, 1851". Therefore, we must also wonder whether Ms. Joll was mistaken (she included no photo of the Christie's silhouette signatures) or whether the pair on ebay had fake signatures (the signatures of the two pieces bore somewhat different handwriting). The simple neat signature "Beaumont" such as the one photographed on the right is well-recorded on the majority of Beaumont's work. One trade label has been recorded.

-

-

William Henry Brown, American Silhouettist (1808-1883)

William Henry Brown was born and died in Charleston, South Carolina. He worked as an engineer in Philadelphia where he lived from 1824 until at least 1841. He began his career as a silhouettist in the 1830s working first in New England and then traveling widely throughout the South. Brown pursued his career as an artist until at least 1859. After 1859, Brown is known to have resumed his work as an engineer.

Although Brown is often compared to Edouart, he began cutting silhouettes almost 15 years before Edouart ever set foot in America. Brown made his debut as a silhouettist in 1824 with a full-length silhouette of General Lafayette. Brown was a mere sixteen years old at the time. Like Hubard, Brown was considered a child prodigy. Also like Hubard and Edouart, Brown cut his silhouettes freehand with common scissors. His embellishment is subtle and superbly rendered.

Brown often mounted his silhouettes on lithograph backgrounds, made for him by the Kelloggs of Hartford. He is most well known for his book Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans published as a collection of full-length silhouettes with biographical sketches and letters written by the subjects. The book was published in 1846 by E.B. & E.C. Kellogg. Almost the entire edition was destroyed by fire and it is rare to find a complete copy of the book. Luckily, the Kelloggs also published the individual silhouettes from Brown’s book as lithographs. This lithography is most often what can be found on the market from Brown’s career. Original silhouettes are difficult to find despite the fact that Carrick believes he was as prolific as Edouart.

Besides the single figures that we most likely think of when hearing Brown’s name, he was a most industrious artist who cut profiles of an entire train, a fire brigade, and even a funeral procession. His silhouette of the St. Louis Fire brigade contained an engine, two hose carriages, and sixty-five firemen. The finished grouping was 25 feet long! Brown’s rendition of “The De Witt Clinton” train is over six feet long and may be viewed in the Connecticut Historical Society where it has hung since Brown presented it to the Society himself.

-

-

William Chamberlain, American Silhouettist (1790-1860)

Little is known about William Chamberlain although his silhouettes epitomize everything that is loved about American folk silhouettes.

Genealogy research tells us that he was born on April 3 (or 13), 1790, in Loudon, New Hampshire, the child of Captain Moses and Rebecca (Abbot) Chamberlain. He married Mary Ann Baker in 1813 or 1814. Together, they had one daughter, Mary Chamberlain, born in Loudon on August 28, 1835. In the 1850 census, Chamberlain listed himself as a chair-maker, leading us to speculate that either the life of an itinerant silhouettist was not profitable or that he wanted to find a way to stay home with his family. Chamberlain died at age 70 on April 13, 1860. He was buried in the Plains Cemetery, Boscawen, NH.

Carrick, in Shades of Our Ancestors tells us that Chamberlain went on a two-year silhouette cutting tour through Massachusetts, New Hampshire and New York. His grand-daughter, Mrs. Frederick McClure of Worcester, Massachusetts, gave to the American Antiquarian Society ("AAS") eighty-nine hollow-cut silhouettes done by Chamberlain and kept for himself. Chamberlain cut the donated silhouettes during a two year period in which he traveled New England in the 1820s, as an itinerant silhouette artist. Mrs. McClure added a note to her donation saying "He made the profiles with the aid of a profile machine. He usually cut his profiles in duplicate, and these are the ones he preserved." It is these eighty-nine silhouettes that allow us to attribute work to Chamberlain because he never signed nor stamped his work.

Chamberlain's work is hollow cut. He cut the heads of his men, left the collar and shirt front as an uncut part of the background paper, then cut the shoulder to the end of the bust-line. He then drew and painted the shirt and collar details. The women in his duplicate folio are completely hollow cut, from the top of the head to the bottom of the bust-line. I set about examining photocopies of the 89 silhouettes in the duplicate folio sent to me by the AAS and found that Chamberlain cut every silhouette in the folio with the same bust-termination line. Every silhouette that we know with certainty was cut by Chamberlain has a convex curve at the front of the bust-line, coming up at a notch, then a concave curve to the back.

Almost every bust-length hollow cut man in which the collar and shirt front are left uncut with drawn-in details has been attributed to Chamberlain by uneducated dealers. Collectors should beware of such misattributions and look for examples of Chamberlain's work before spending a lot of money on a "Chamberlain" from a dealer who does not specialize in silhouettes. Examples may be found in Carrick's book and Silhouettes in America, 1790-1840 by Blume J. Rifken.1 I am currently offering a copy of both of the reference books on the Books page.

1After studying photocopies of the silhouettes in the Chamberlain duplicate book, I must disagree with Rifken's attribution to Chamberlain on pages 50-51. While Chamberlain might have cut those silhouettes, the bust termination is not the same as those in the duplicate book, which are the only ones we know with certainly were made by Chamberlain.

Please view the Chamberlain silhouettes currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

Augustus Day (active 1800 - at least 1845)

Augustus Day was a carver, gilder, portraitist and silhouettist. He advertised as a physiognotrace profilist in Charleston, South Carolina in 1804. Most of his work seems to have been done in Philadelphia where he advertised as carver and gilder (1800-1806, 1814-1821), looking glass maker (1823-1825), and painter (1829-1833). His hollow cut silhouettes are impressed with a stamped signature "DAY'S PATENT" and his painted silhouettes were hand signed "Day Fecit". His very desirable painted silhouettes were either black with soft painted hair tendrils and frilled ladies' collars painted with a soft grey-blue tone; or the more desirable olive-green and elaborately gilt embellished. His hollow cut silhouettes are more scarcely found than his painted profiles and, indeed, are some of the most rare of signed American silhouettes.

-

-

De Hart's silhouette of George Washington

Scan from Van Leer, Carrick,

Shades of Our Ancestors. Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1928. Plate after Page 18.

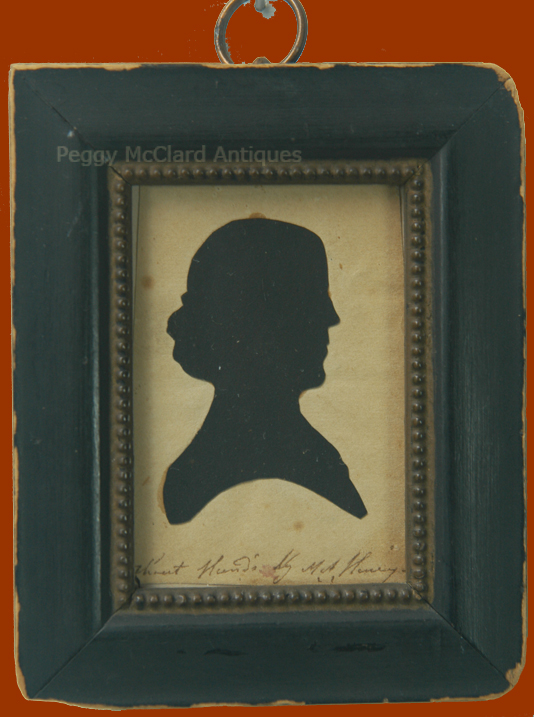

Sarah De Hart, American Silhouettist (1759-1832)

Sarah De Hart was one of the first American born silhouette artists and the earliest recorded American woman silhouettist. She was born on February 13, 1759 in Elizabethtown, NJ. (Although Charles Willson Peale is not known to have started cutting silhouettes until 1802, he was born 18 years earlier than De Hart, in Chestertown, MD in 1741.) De Hart’s earliest discovered silhouette was cut when she was twelve years old, in 1771. Unlike the majority of American silhouettists who would come later, De Hart cut her hollow cut silhouettes without the aid of the physiognotrace devices that were so popular in the 19th century. To date, no evidence has been discovered showing that De Hart cut silhouettes for profit, but she certainly captured the heart of George Washington for whom she cut several likenesses after visiting Mount Vernon with Washington’s sister Abigail Mayo in 1786. De Hart’s work is extremely rare (possibly because she only cut silhouettes for her own pleasure and the pleasure of friends and family). A group of about 130 of her works descended through her family until 1946 when the collection was sold to a collector. The collection was ultimately disbursed through auction in 1997.

-

-

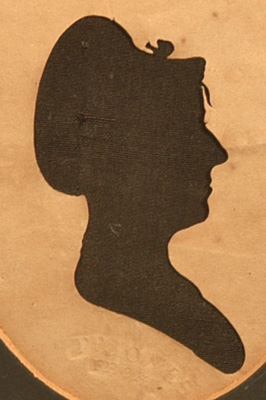

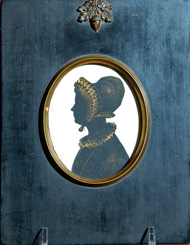

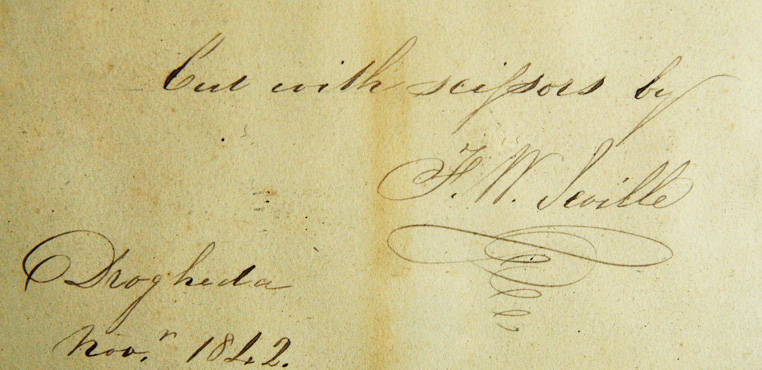

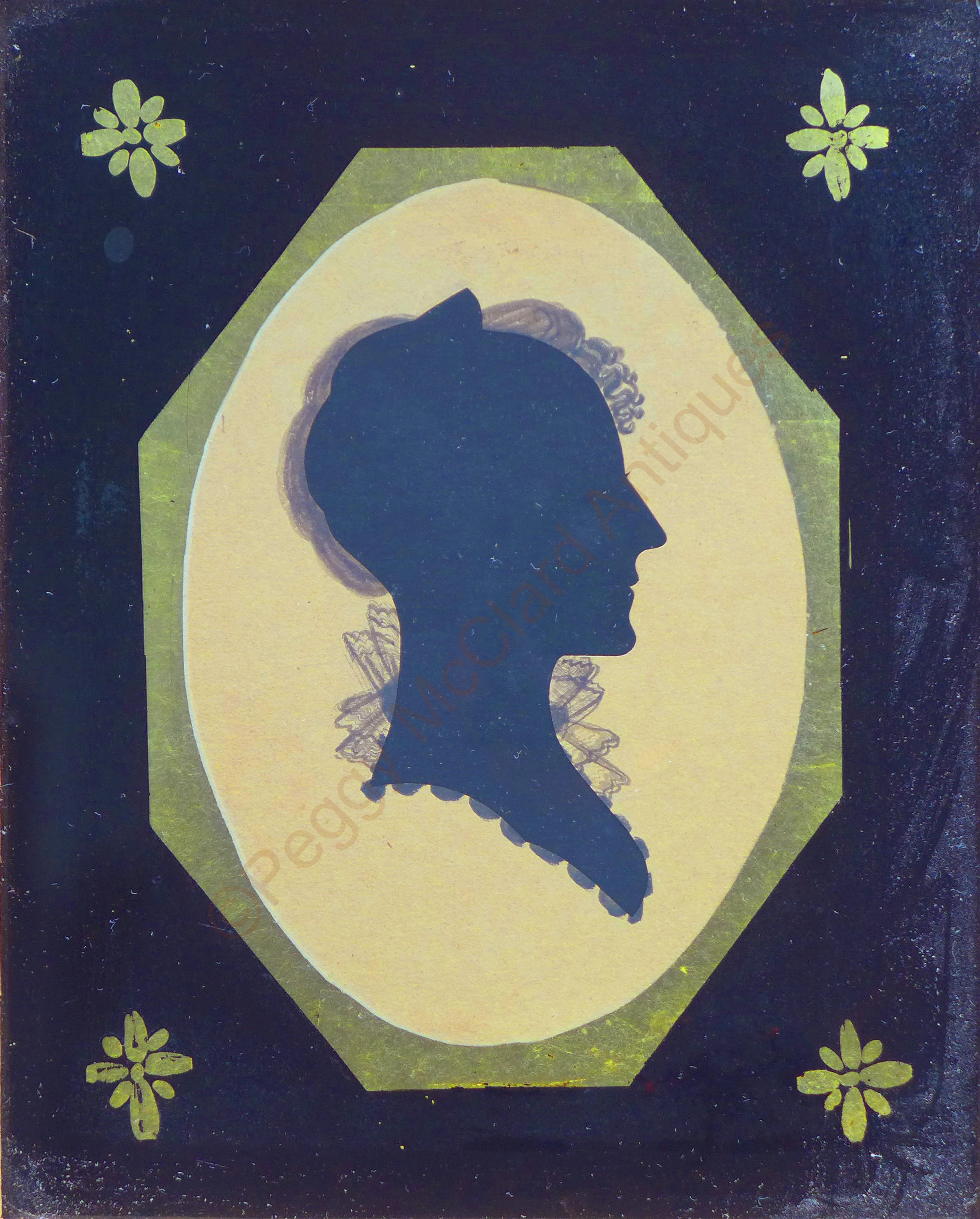

John Dempsey (active circa 1822-1844)

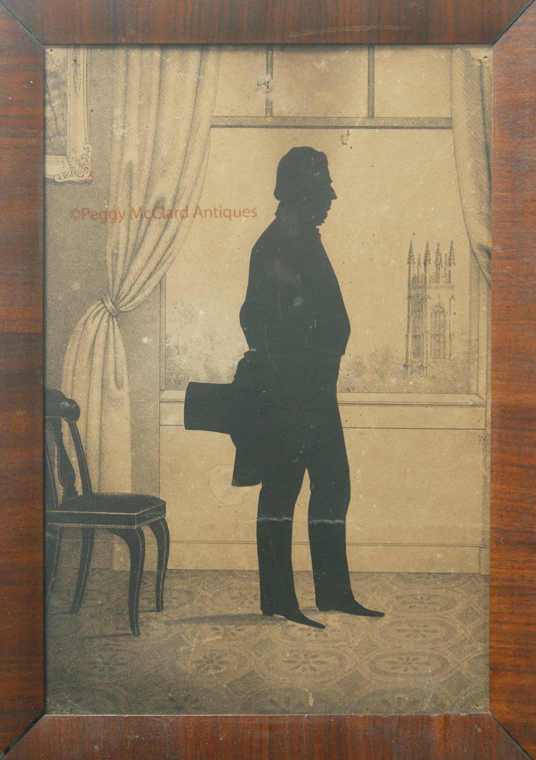

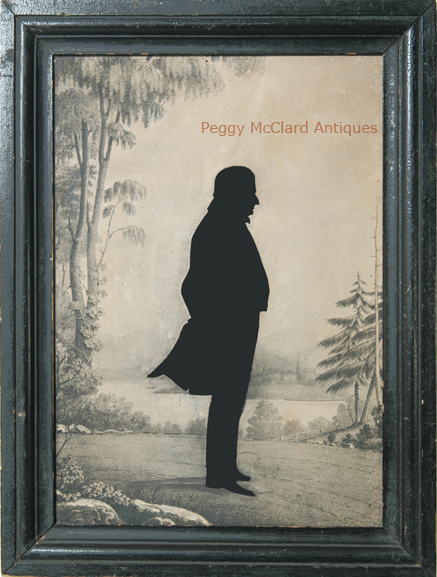

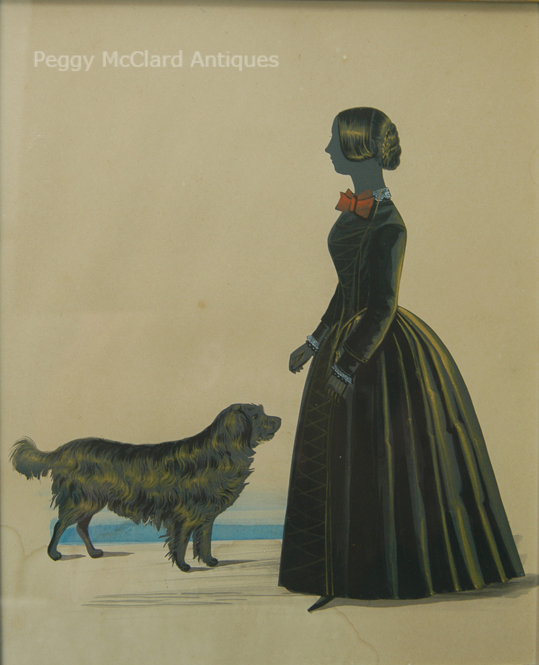

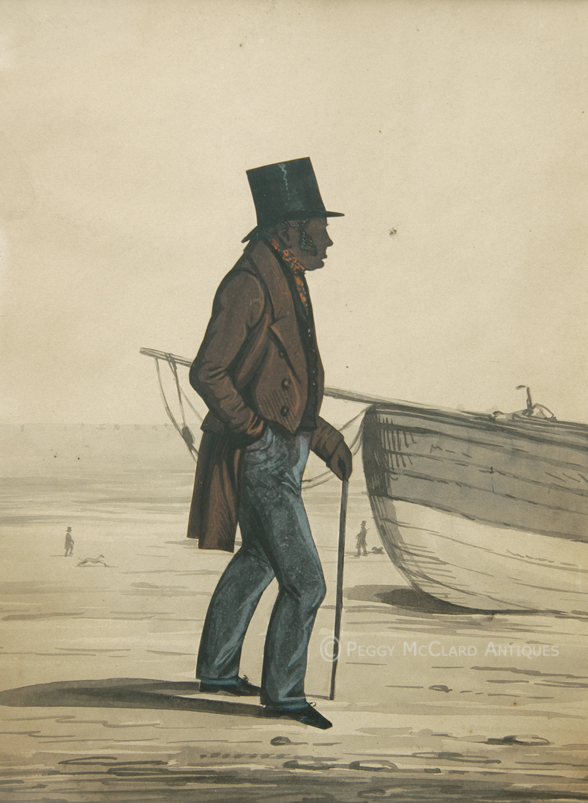

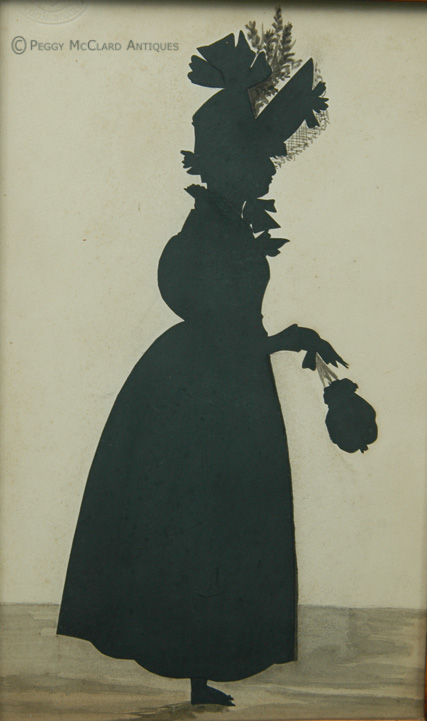

Little is known of John Dempsey's life. We know, through one of his advertisements, that he worked as an itinerant silhouettist beginning in the 1820s and that by 1840, he had cut silhouettes in England, Ireland and Scotland. He advertised that he took "Likenesses in Shade 3d./Bronzed 6d./Coloured Is. 6d and upwards. . . . ." He is best known for his full-length colored silhouettes, such as this one offered, in which his skill as an artist shines. McKechnie tells us "Dempsey's work in this field is so cleverly cut and pasted down that it is sometimes almost impossible to see the cut edge. The edge is concealed not by painting, but simply by skilled craftsmanship." McKechnie, Sue, British Silhouette Artists and their Work: 1760-1860. Sotheby Park Bernet, 1978 at 202. Indeed, this lady looks fully painted. The edges of the pasted paper are so skillfully painted that you almost need to remove the silhouette from the frame so that you can feel the raised edge. Dempsey kept a sample book showing his silhouette-making techniques. This was not a duplicate book, like Edouart, Bache or Chamberlain kept, but a book from which customers could pick the style of silhouette they preferred. The book included India ink painted bust profiles as well as full length painted profiles pasted to painted landscape backgrounds. Perhaps Dempsey's most important work is a large conversation silhouette titled, Liverpool Exchange showing eight-five figures upon a painted background showing the Exchange Buildings of Liverpool. Edouart apparently felt somewhat threatened by Dempsey's beautiful work. Edouart wrote that the use of color in silhouettes was "harlequinades" and he could not "understand how persons can have so bad and I may say, a childish taste!" August Edouart, A Treatise on Silhouette Likenesses, London, 1835. 24. It is generally understood among silhouette scholars that Edouart was referring to Dempsey's work. Edouart was always quick to lash out at those he felt most threatened by. Obviously, he felt threatened by Dempsey's beautiful work.

-

-

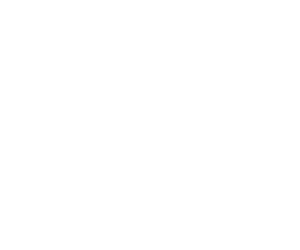

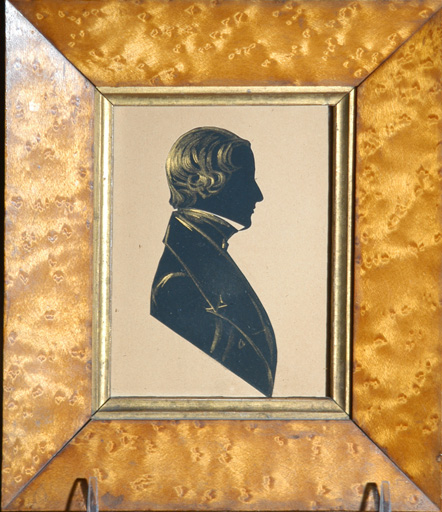

William M.S. Doyle, American Silhouettist (1769-1828)

William Massey Stroud Doyle was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1769. His father was a British soldier, but Doyle seems to have lived and worked his entire life in Boston. Doyle was a silhouettist, artist of portraits of both full-size and miniature. He worked in silhouette cutting, watercolor, oil and pastel. His silhouettes were beautifully rendered in hollow cut or paint (sometimes painted on plaster in the manner of Miers).

Doyle did not confine himself to his artistic endeavors. Indeed from 1806 until his death in 1828, Doyle, in partnership with Daniel Bowen, was one of the owners of the Columbian Museum. Together, the two men built a five story building in 1806 to house the museum. The five story building in 1806 towered over the surrounding landscape like a skyscraper! Unfortunately, the building burned to the ground in 1807, and the two men built a smaller building which they used for the museum until 1825.

In 1811, Doyle placed the following advertisement:

Wm. M.S. Doyle

Miniature and Profile Painter

TREMONT STREET, BOSTON, next House north of the Stone-Chapel, the late residence of R.G. AMORY esq. Continues to execute Likenesses in Miniature and Profiles of various sizes (the latter in shade or natural colors) in a style peculiarly striking and elegant, whereby the most forcible animation is obtained.

Some are finished on composition in the manner of the celebrated Miers of London.

Prices of Profiles—from 25 cents to 1, 2, & 5 dollars.

Miniatures—12, 15, 18 and 20 dollars.

Doyle’s silhouettes certainly live up to his salesmanship in that they are “peculiarly striking and elegant” and “the most forcible animation” truly is obtained. Rarely do they real ones come onto the market (although it is quite common to find 20th century fakes). What few there were (for Doyle did more portrait painting that silhouette cutting or painting) have all been snapped up into private collections and museums.

Please view the Doyle silhouettes currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

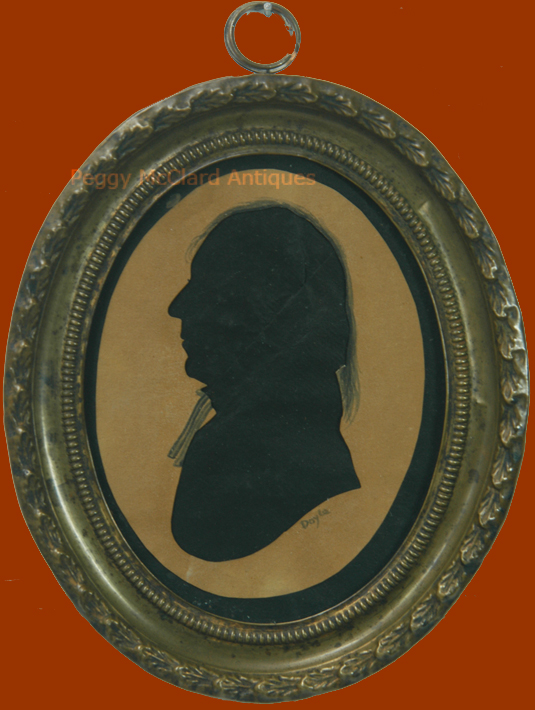

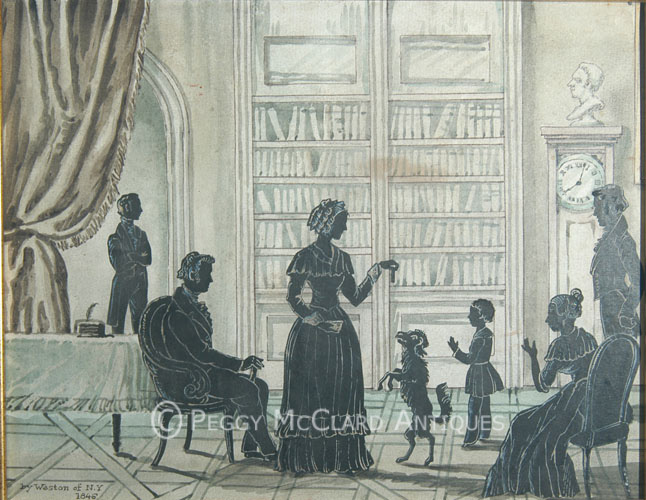

Augustin-Amant-Constan-Fidèle Edouart (1789-1861)

Edouart, born in the French harbour-town of Dunkerque, was a decorated member of Napoleon’s army. After the war, he was forced to move to England when he lost most of his property during the Evacuation of Holland. Like many French émigrés of that day, Edouart first tried to make a living teaching French. Finding too many rivals to excel as a teacher, this gifted artist turned his attention to hair art. Edouart made the intricate hair pictures that we are familiar with as mourning art, the plaited and floral ornaments which are commonly seen, and also wax portraits in which he embedded the natural hair to give a natural appearance. He excelled in the field of hair art in the same way as he would later exceed in silhouette cutting.

Edouart began silhouette cutting as the result of a heated argument with a friend who wished to commission a silhouette by an artist who used a mechanical contraption to cut profiles. In an effort to show that mechanics were inferior, Edouart sat the gentleman down, seized a pair of scissors from a nearby desk, blackened a quickly torn piece of paper with candle snuffers and snipped a silhouette of superior quality to that which the family had planned to commission. Edouart is said to have cut perfectly executed silhouettes in less than 2 minutes.

Edouart spent 24 years cutting what has been estimated as more than one hundred thousand silhouettes. He have believed that Edouart coined the term “silhouettist” because he was insulted by the then-common term “black-shade man.” By 1826, Edouart was cutting silhouettes exclusively of his hair work. He cut two original profiles of every sitting and kept one of each of the originals, named and dated, in his many folios. In 1835, Edouart wrote and published a book, A Treatise on Silhouette Likenesses.

Edouart traveled throughout England, continuously cutting silhouettes before first coming to America in 1839. He stayed in this country for ten years, cutting and cataloging silhouettes of the most important Americans of the time. Edouart cut silhouettes of six Presidents and ex-Presidents, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Supreme Court Chief Justice Joseph Story, and Madame Jumel who became the model for Charles Dickens’ mad Mrs. Havisham in Great Expectations to name a few.

In 1849, Edouart set out to return to England on the ill-fated ship, Oneida, which wrecked off the island of Guernsey. Although all of the passengers and crew were saved, only fourteen of Edouart’s folios were rescued. Broken-hearted by the loss of his life’s work, Edouart abandoned his profession and returned to France where he died at the age of 72. Edouart gave the rescued folios to the Lukis family, who had cared for him during the months following the shipwreck. There the folios stayed until, in 1911, Mrs. F. Nevill Jackson advertised to buy silhouettes for research she was conducting. The Lukis family sold the precious folios to her. Mrs. Jackson meticulously cataloged each silhouette. Where the background paper was waterlogged, she carefully removed the silhouettes and placed them on new background paper. Upon removal, she was delighted to find that Edouart had written the name of the sitter and date on the back of each silhouette as well as the bottom of each page. Mrs. Jackson cut keyholes into the new background paper so that Edouart’s written description could be seen. Where possible, she also cut his written descriptions from the bottom of the original folio pages and pasted them to the bottom of the new pages.

Mrs. Jackson eventually sold the six folios with American silhouettes to Arthur Vernay of New York. Mr. Vernay sold the majority of the American duplicates at a 3-week sale in 1913. One remaining unbroken American folio was kept by Mr. Vernay and made the subject of Auguste Edouart's Silhouettes of Eminent Americans, 1839-1844, by Andrew Oliver. Eight hundred sixty-two individual American duplicates were eventually sold to renown silhouette collector Reverend Glenn Tilley Morse.

Edouart is known for his simple and lifelike full-bodied silhouettes which are ripe with action. He used no colored embellishment, denouncing gilding, coral necklaces, and colored dresses as harlequinades. Although Edouart pronounced that “the representation of a shade can only be executed by an outline,” beginning in 1842, he sometimes penciled or chalked indications of hair, the lines of a coat, buttons and fingers. His ultimate surrender to the use of some embellishment was probably a nod to the overtaking of his profession by the daguerreotypists. However, he always refused to use bronzing or any other color in the embellishment of his figures.

Edouart cut and assembled compositions of entire families, often backing them with stock lithographs of room or outdoor settings. Less common are his watercolor backgrounds in sepia tones. What is expected and delightfully delivered in the Edouart silhouettes are accessories such as hats, canes, letters--even family pets. His silhouette of Mrs. Mary Appleton depicts her cutting a silhouette herself. The tiny additional profile is said to be remarkably recognizable as Mrs. Appleton’s husband.

A new and exciting discovery recently surfaced from a Parisian bookseller: Edouart’s personal folio of “Scraps” in a book labeled “Animaux”. This is the most Edouart exciting discovery in a century! Mrs. Jackson discovered the duplicate folios in the first decade of the 20th century. It appears that Edouart took this scrapbook with him to Calais. It was filled with figures of dogs, horses, toys, mythical characters, floral sprays, and on and on. It looks like Edouart used the book to keep practice figures of unusual forms that he might have been commissioned to add to conversation silhouettes as well as figures that he cut for his own amusement and for his traveling exhibition. Animaux was a treasure trove of incredible pieces. I have been so lucky to acquire more than 200 figures removed from this book. In the coming months, I will be offering these mind-boggling silhouettes for sale. They will always be lightly mounted on acid-free materials and framed in period frames. The reverse of the mountings will always be stamped with a specially made stamp for items from this book and also with my collection stamp. The reason for my insistence on mounting and stamping is because these figures are so unusual (although distinctly from Edouart’s hand) that I want to help future generations authenticate them because they can be traced back to me.

The most complete information about Edouart can be found in the following reference books:

Jackson, E. Nevill, Silhouettes: A History and Dictionary of Artists, Peter Smith Publisher, Incorporated, 1979. Plate 14.

McKechnie, Sue, British Silhouette Artists and their Work: 1760-1860, P. Wilson for Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978 at plate 360, page 299.

I usually have a copy of both offered for sale on my Books

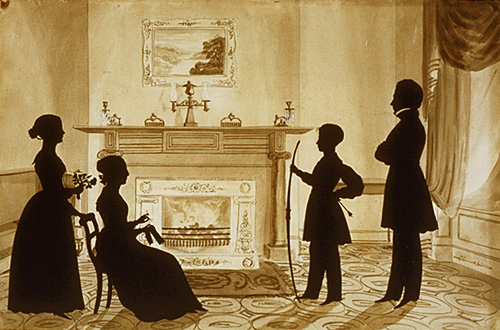

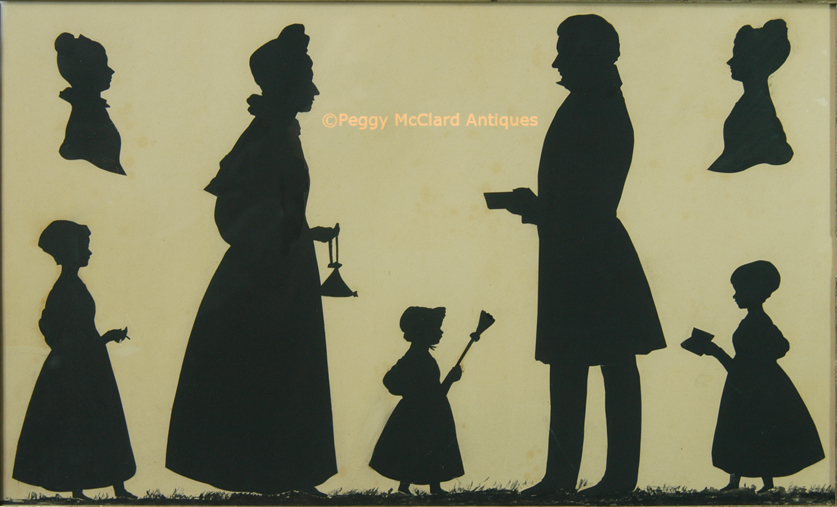

page.I am very pleased to be able to show you an Edouart silhouette, complete with watercolor, graphite and ink background as commissioned by the James R. Westcott family of Saratoga Springs alongside Edouart's duplicate silhouette of the Westcott family as taken from the rescued folios. You will notice that the commissioned silhouette (to the immediate left) includes (from left to right) daughter Marie, wife Mary, son James Gardner Westcott, and father James Randell Wescott. The duplicate (to the immediate right) includes Marie and Louisa (or Louise) P. Westcott, wife Mary and James R. Wescott. Remember that when Mrs. Jackson bought the rescued folios from the Lukis family, many of the silhouettes were missing from the pages as a result of their trip to the bottom of the bay. Apparently, James Gardner Westcott was one of the missing folio silhouettes. The commissioned silhouette of the Westcott family is dated 1840 and Marie, Mary and James R. are dated 1841 in the folio. I have absolutely no explanation for why the dates are different on the commissioned silhouette and the folio silhouettes. Louisa is dated 1843 in the folio and only she bears the faint chalk line embellishment that Edouart used starting in 1842. I surmise that Louisa was a member of James Randell Westcott's extended family who had her silhouette cut later. Edouart often went back in the folio to add a later-cut family member or add a notation about a death or marriage of a sitter. It would not have been unusual for him to have added Louisa to the Westcott family page later. We know she was placed on the same folio page as Marie before Mrs. Jackson restored the silhouettes because their names are written together on the inscription that Mrs. Jackson cut from the damaged folio page and pasted to the bottom of the later paper. Many thanks to the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec for granting permission to display a photo of the commissioned silhouette for this website.

Please view the Edouart silhouettes currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

John Field (1772-1848)

Much of his career was spent working for John Miers Studio. Please see the entry for Miers below.

Please view the Field silhouettes currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

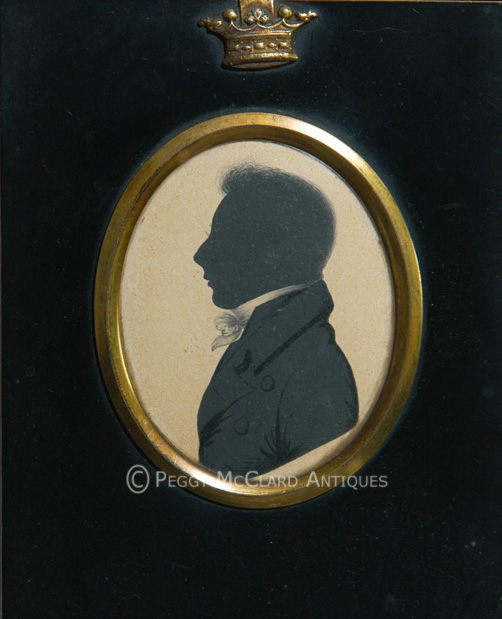

Edward Foster (1762-1864)

Edward Foster was born November 8, 1762, two years into the reign of the monarch who would become his most important, George III. Foster's father was a gentleman land-steward and mother was the child of nobility. He joined the Derbyshire militia at the age of 17 and remained in the military for 25 years. Once Foster retired from the military at age 42, he turned his attention to his artistic talents where he earned a fine reputation as a painter of miniatures and profiles. King George III appointed Foster the "Official Miniature Painter to the Royal Family" and moved him into lavish apartments in the Round Tower of Windsor Palace. Foster set up his business as a professional silhouettist in London around 1811 on The Strand. It was around the year 1811 that Foster began using papier mâché frames with a special brass hanger bearing his name above the Royal crown, meaning his appointment as Offical Miniature Painter must have been made by at least this date. In addition to working from his studio, Foster traveled as an itinerant artist. It appears that Foster returned to Derby in about 1832, during which year he was seventy-two years old. Never one to rest on his laurels, Foster began drawing and printing educational maps and charts for school use. He was married five times and had at least 17 children, only one of whom survived his death at 102 years old in 1864.

Foster's silhouette profiles were fully painted (not cut). His work is generally categorized as two types: "black profiles" with which he appears to have launched his career and later "red profiles." For his black profiles, he used thin black paint with detail added with pigment added to gum arabic and, sometimes, Chinese white. His "red profiles" are created with Venetian red and reddish-brown to which he added touches of gold and Chinese white. He used a three-dot technique to depict the transparency of the fabrics of women's dresses. Neck and shirt frills were generally left without color.

Peter Seddon, Derbyshire Life Magazine, July 2009 at 170-173.

Also see a great article about Edward Foster by Brett Payne at Photo Sleuth-blog

-

-

F. & H.A. Frith (after 1837-1854)

These brothers worked for much of their career as the Royal Victoria Gallery. Please see Royal Victoria Gallery below for information about the Frith Brothers.

Please view the Frith silhouette currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

John Gapp (active 1823-1839)

The Royal Suspension Pier (aka The Royal Chain Pier) was the first major pier built in Brighton, England. When built in 1823, it was intended as a landing stage for incoming ships. But Brighton provided a variety of amusements to draw tourists and the spaces between the cast-iron towers from which the chains were suspended soon attached profilists to set up shop in order to provide tourists with a memento of their visit to Brighton. John Gapp set up at the Third Tower in 1828 or earlier and seemed to have an ongoing rivalry with another silhouettist, Edward Haines, who had a similar style and had a gallery in the First Tower.

Gapp’s trade labels announce that he produced “likenesses from the scissors only” and that he captured “the expression and peculiarity of character are brought into action in a very superior style.” By 1830, Gapp’s trade label proclaimed “that he has no connexion with any other Person”. This is the first notice of his rivalry with Haines. Gapp’s price list is given as follows:

- Full-length Likeness 2s 6d. each

- Two Full-length Likenesses 4s. 0d. for two

- Likeness in Bronze 4s. 0d.

- Profile to the Bust 1s. 0d.

- Two of the same as above 1s. 6d.

- Ladies and Gentlemen on Horseback 7s. 6d.

- Single Horses 5s. 0d

- Dogs 1s. 6d.

Gapp's naïve cut & paste silhouettes are almost always full length and his subjects almost always have something in their hands. He seemed to have trouble depicting two legs without having the legs look too thick, so, early in his career, he started perching his sitters on what appeared to be one leg with two feet. The cut details of his clothing has been called "spikey" because of the very definitive corners that he cut. His figures are mounted on card with either a simple watercolor wash ground or no background at all. He seldom embellished his work.

-

Hinton Gibbs (active late 1790s - c. 1822)

Hinton Gibbs (incorrectly recorded by Jackson as "Hintor Gibbs") spent most of his profilist career in the militia. His army career appears to have started as a drummer in 1793 while he was probably a teenager. Gibbs appears to have reached the rank of corporal, apparently leaving the army shortly before the Battle of Waterloo. At least four if Gibbs' known trade labels appear to have been used during his military career. After leaving the army, Gibbs seems to have worked in London.

Gibbs painted silhouettes on the reverse of convex glass using two different methods. One style was almost entirely in solid black while the other was done with the finest detail leaving a transparent look to the black paint. He produced incredible detail by scratching the surface of the finger-painted black base with a needle and appears to have rendered detail outside the basic profile with a fine brush. Gibbs appears to have saved this highly detailed style for the profiles of women and children. The accuracy of Gibbs' depiction of women's clothing has given us great insight into the styles of the period.

Generally, Gibbs backed his work with wax. Most of the wax has become damaged or has been removed. Gibbs painted his early work on thick glass and framed them in oval turned wood frames. He painted his later works on convex glass of normal thickness and set them in papier mâché frames.

Please view the Hinton Gibbs silhouette currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

Style 1J.H. Gillespie, Profile Artist (1793-after 1849)

James H. Gillespie started his career as a painter of miniature portraits and silhouettes in England as early as 1810, although the earliest known dated example of his work was done in 1816. He crossed the globe to enter Nova Scotia in the 1820s. From Canada, he migrated into the United States where he is known to have worked in Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Maine. His advertisements tell us that he charged 25 cents for plain black profiles, 50 cents for profiles shaded in black, 1 dollar to finish the silhouettes in bronze and 2 dollars for “Features neatly painted in colours.” The outlines for his silhouettes and portraits were achieved by means of “several mechanical and optical instruments.” His demand was so great that, to save time that the sitter needed be present, he took outlines of the sitters in the morning and completed the rest of the portrait later that same day. The demand for Gillespie's work also allowed him to increase the price of his color portraits from $2 to $4 by the time he hit Baltimore in 1837. By 1842, Gillespie's U.S. tour was finished and he was working in Toronto, where he stayed until at least 1849.

Gillespie painted miniature portraits and silhouettes with a practiced and careful hand. The features are crisply delineated and his painting style is similar to the work of an artist who painted portraits on ivory. I am, however, unaware of any portraits on ivory that have been attributed to him. His silhouettes are generally found painted in shades of dark grey with black pigment added to show clothing details. His use of gum Arabic to heighten detail is masterful and subtle. Several monotone portraits backed by dark grey painted background have been found and are quite distinctive.

As a result of their recent research into the life and work of Gillespie, Suzanne and Michael Payne note that Gillespie worked in six distinctive styles:

Style 1: Simple silhouette--profile head and neck painted in grey-black with gum arabic highlights of the ear, eye, and the hair. No watercolor detail added. The Paynes tell us this was his 25-cent portrait.

Style 2: Silhouette face with painted body--profile face painted grey-black with body carefully outlined and then painted in dark colors. No gum arabic detailing the face or hair, but painted hair strands added. Eyelashes are drawn with delicate brushstrokes. Neck between face and body is outlined, with details added. Extensive use of gum arabic to highlight the clothing. According to the Paynes, this was his 50-cent profile.

Style 3: White face on black background--profiled face shows the features carefully modeled using pencil, ink, and grey wash watercolor details. The painted grey-black (carefully painted with no brushstrokes) provides contrast. Sitter's clothing is depicted in a grey-black that is either slightly lighter or darker than the background. Thick gum arabic highlights the clothing with a very think line of gum arabic defining the bust. This monochromatic style appear to be the portrait that Gillespie advertised as "in imitation of Copper-Plate busts." These portraits sold for 5 shillings while he was working in England. My own notation to the Paynes' descriptions of this style is that I have seen several on which the background and features are painted a brownish-copper color that closely seems to imitate the sepia tones of many copper plate prints of the period. To the left you can see an example with the grey-black and one with the brownish-copper painting. Recently, I have acquired a portrait done in imitation of copper plate print but with a touch of color added in the young girl's red hair.

Style 4: Silhouette with bronzed highlights--profile painted grey-black with bronze paint highlights used for hair, ear, necklace, and dress. According to the Paynes, Gillespie charged $1 for this portrait style.

Style 5: Watercolor profile portrait--profile painted with watercolor, ink and pencil used to model the features. A distinctive background shading provides what Gillespie advertised as "drapery". This background provides a good means for identifying his work. Shading around the perimeter of the portrait is achieved with large dabs of dark browns and blues concentrated on the lower right and left sides of the figure and a light blue color applied with minute brushstrokes on the top. The darker drapery catches the viewer's eye first and draws it towards the face. A few examples have only light blue coloration around the entire perimeter of the portrait. Clothing usually painted in dark tones of black or blue, with colored buttons or jewelry and gum arabic highlights. These oval portraits have been found in lockets, wood frames, and stamped brass frames. It appears that Gillespie produced more of this style in the U.S. than the other five styles. The Paynes tell us that this is the style that Gillespie first offered for $2 and later for $4.

Style 6: Less detailed watercolor profile portrait--profile face is less modeled and simpler than style 5. The body is less elaborately drawn and there is no background shading. This style has only been found framed in a square format. This style has been found with sitters from Maine and Canada. Gillespie's price for this style is unknown.

Payne, Suzanne Rudnick and Payne, Michael R., "Six Choices for the Sitter, James H. Gillespie (1793-after 1849)", Antiques & Fine Art, 200 (Summer/Autumn 2008) (online article at antiquesandfineart.com).

Please view the Gillespie profile currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

Style 2

Style 2

-

Style 3

Style 3

-

Style 4

Style 4

-

Style 5

Style 5

-

-

-

Sarah Harrington (active about 1774-1787)

Sarah Harrington is an enigma to say the least. Her successful career as a silhouettist might lead one to believe she was an 18th century proponent of women’s rights, but that does not appear to be the case. Mrs. Harrington (for I would not expect her to approve if I referred to her as Ms.) began her notoriety by authoring a book of instructions of ladies’ virtues. Her book, which was published in at least 4 editions was dedicated to Princess Amelia Sophia Eleanor. The dedication reads (in part)

Your ineffable mildness, and amiable disposition, accompanied by a noble and generous expansion of heart, are virtues that will naturally encourage and invite the timorous; attracted by those realities, with deference and respect I approach your Highness, . . . , upon consideration of with the Author has done her best for the service of her sex; I have endeavoured (as far as my weak abilities would permit) to contribute my mite in the promotion of sound and useful Knowledge, with an humble endeavour to point out the most effectual means of rendering permanently happy, not my own sex in particular, but the whole nation in general. . . . .

Mrs. Harrington’s book discussed the permissible amusements of an 18th century lady: 1. The Use of the Globes (which Mrs. H. taught—to ladies only); 2. Geography and Maps (part of the above described lessons); 3. Astronomy; 4. Reading; 5. Epistolary Correspondence, or Letter Writing; 6. Poetry; 7. Music; 8. Drawing. The book also described the proper Entertaining Amusments: 1. Dancing; 2. Theatrical Entertainments; and 3. Singing, etc.

The proper Mrs. Harrington later published a treatise on the knowledge and use of maps as well as a second treatise of proper womanly amusements. In this second treatise, she deplored “the amazing increase of Dissipations of almost every kind, at present seems to fascinate our minds, and occasion an almost total neglect of those Refinements so necessary to real happiness of human beings.”

In light of Mrs. Harrington’s concern of the properness of ladies’ activities, it seems out of character that she became so successful in her profession as a silhouettist, that in 1775, Sarah Harrington applied to patent her method of producing profiles. Her patent was accepted and she became a very successful itinerant artist.

Apparently, Mrs. Harrington’s silhouette business was extremely lucrative in university towns. Numerous advertisements aimed at “the Gentlemen of the University” show that she worked in Oxford and Cambridge often and that, as time advanced, her lodgings (where she also accepted customers) were found at more distinguishable addresses.

Hollow-cut silhouettes are rare from the British Isles after 1790. During the period that Mrs. Harrington cut her lovely hollow-cut silhouettes, few others joined her (the most notable exceptions are Mrs. Beetham and Mrs. Collins). Mrs. Harrington did not use trade labels until after 1782. Her earlier silhouettes are rarely inscribed with her signature on the back of the frames. It is believed that since she was one of the earliest silhouettists, she did not have sufficient competition to warrant labeling her work until the 1780s.

Mrs. Harrington’s work is recognized by the roughly textured black paper she used to back her exquisitely cut silhouettes. Also, while most 18th century silhouettists of the hollow-cut method often left a slash from the base of the paper to the base of the bust-line showing the knife entry to the paper, Mrs. Harrington took great care in making the entry of her knife as little noticeable as possible. She also took great care when rendering eyelashes and cut bows very simply and cleanly. She represented men’s shirt frills as scallops and cut the buttons on a man’s shirt as triangles.

-

-

Charles Samuel Hervé II (1785-1866)

Charles Samuel Hervé II was a miniature painter, silhouette artist, professor of music, manager of the Prosopographus gallery and a fruit farmer. He worked at various addresses in London under his own name and with his nephew, Alfred Hervé, Count de la Monnière.

Recent research shows that Hervé was probably the mysterious “Prosopographus, the Automation Artist.” Handbills have been found showing that Hervé managed the mysterious gallery which appears to have been active from 1818 until the end of the 1820s. In fact, the found handbills advertised that Hervé invented the illustrious “Prosopographus,” a machine that drew the basic outline of the sitter’s profile. It is believed that Hervé’s assistants procured the basic outline via the machine, but Hervé cut and painted the silhouettes.

Hervé also worked for William Miers for a period of about 5 years. William Miers was the son of the great silhouettist John Miers. William was a profilist in his own right, but concentrated his work primarily on frame-making. It appears that Miers hired Hervé to produce copies of John Meirs’ great work for later orders. Hervé is known to have been an exceptional artist at copying other’s styles and works as well as producing extraordinary silhouettes from life in his own great style.

When working from his own gallery, Hervé used stencils to identify his work, as did his nephew Alfred. Stencils showing only the Hervé surname must be assumed to be Charles. As the elder family artist, he would have the right to the surname. Alfred’s stencils, while similar in style and fonts, identify the artist as “A. Hervé.”

Please view the Hervé silhouettes currently in offered on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

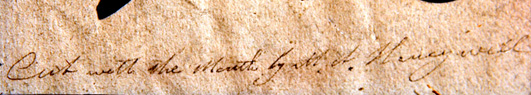

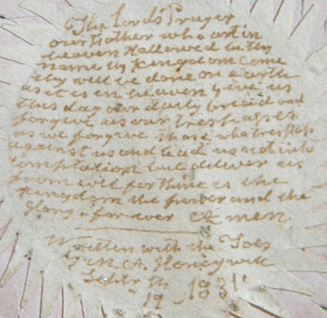

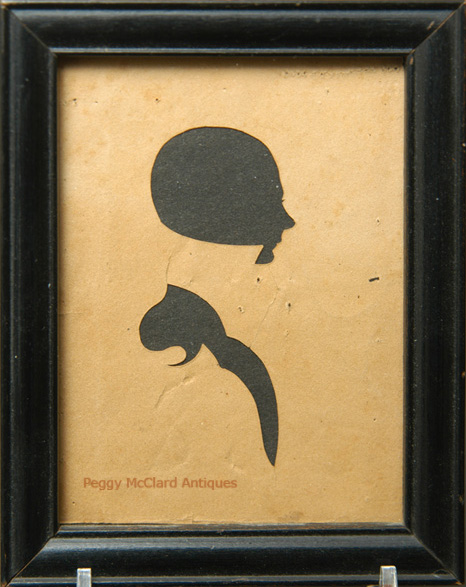

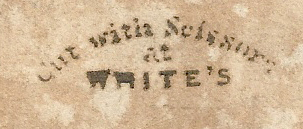

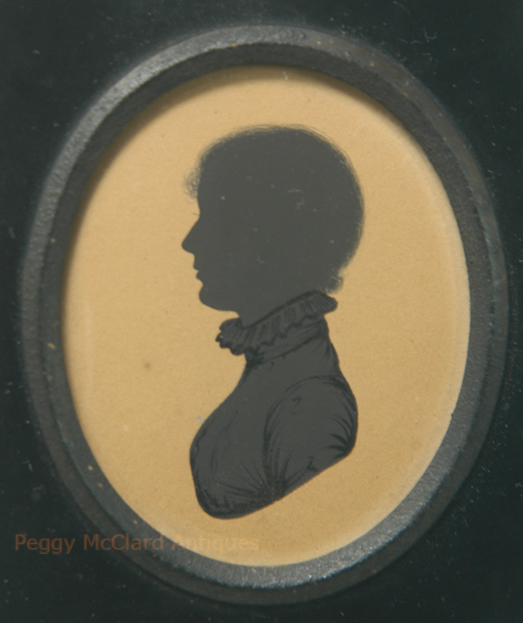

Martha Ann Honeywell (about 1787-after 1848)

Like Hubard, Martha Ann Honeywell was a child prodigy. While her silhouettes are more naïve, even a bit clumsy than Master Hubard’s, part of the charm of Miss Honeywell’s silhouettes is the triumph to human accomplishments that she could even produce them at all. Miss Honeywell was born around 1787 in Lempster, New Hampshire with only the first joints of both arms, and one foot with only three toes. The first broadsides announcing her profession of profile cutting appear in 1806 and continue until 1848. The signature on Miss Honeywell’s cut & paste silhouettes proclaims either “Cut without hands by M.A. Honeywell” or "Cut with the Mouth by M. A. Honeywell". Most of the silhouettes are plain, but a few gilded examples have been recorded.

While Miss Honeywell was traveling along the Eastern shore board of America and to Europe to cut her silhouettes, she also offered finely stitched needlepoint watch papers, wrote tiny verse with her mouth and did Scherenschnitte (scissor-cuttings). Pictured are examples of both—the needlepoint is wonderfully executed and the verse is so tiny it requires a magnifying glass to read. With magnification, one sees that it is the entire Lord's Prayer, written within less than three-quarters of an inch of paper.

Please view the Honeywell silhouette currently in offered on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

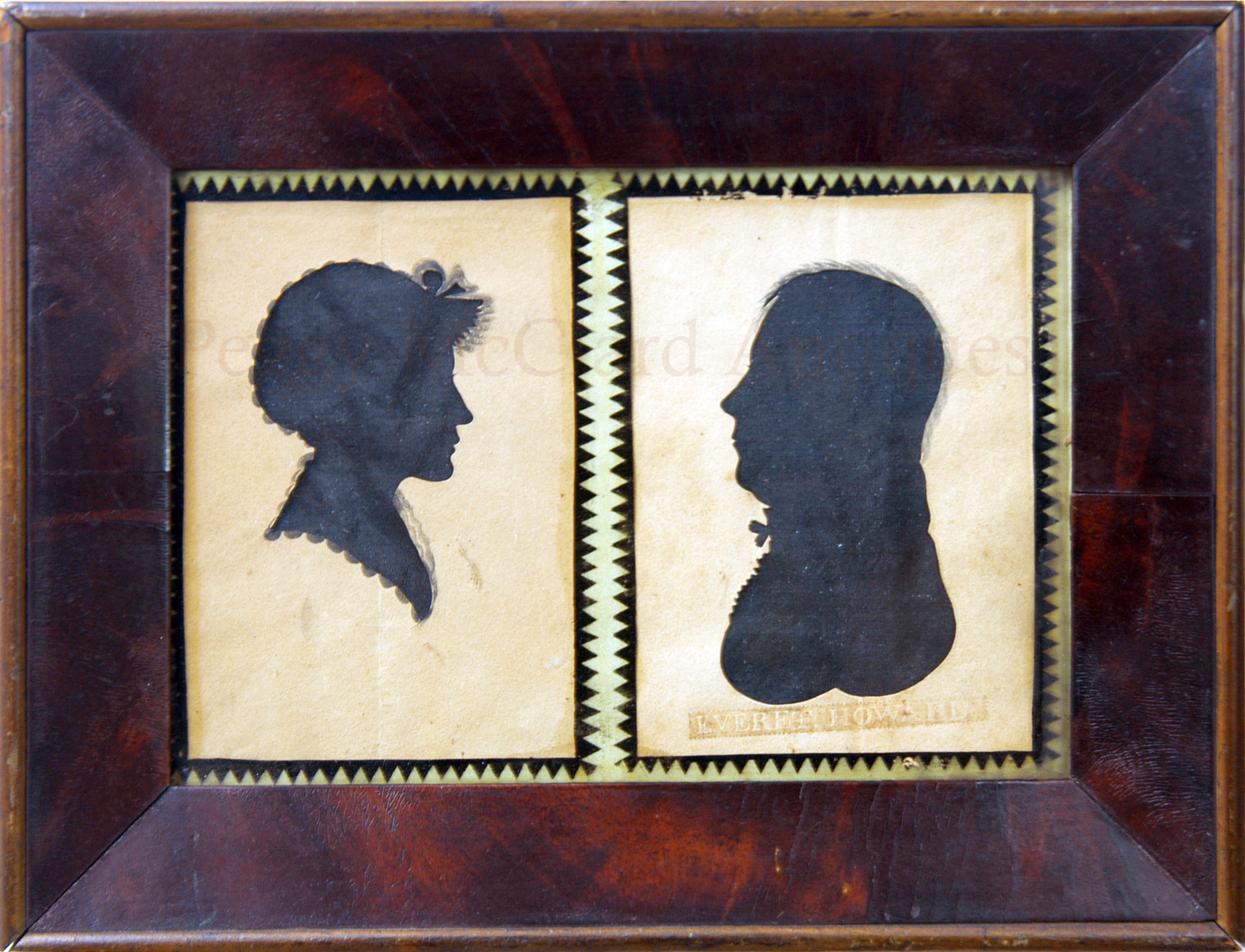

Everet Howard, American Silhouettist (1787-1833)

Everet Howard, my favorite American silhouette artist, was born in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, November 22, 1787. His family moved to Leeds, Maine in 1801. He taught school for a time but, tired of teaching unruly young scholars, he quit his job and began to look for something else to do. Always a budding artist, Howard loved to “draught likenesses” of friends and dabbled in landscapes. In April, 1807, Howard “got a good horse to ride to the Westward” and commenced making preparations to journey west, through New Hampshire, Vermont and New York. It isn’t clear what Howard intended to for money—perhaps he would find another schoolmaster position or visit with relatives as his brother had done. But, a few days before his scheduled departure, Howard decided to “invent” a profile machine and become a profile artist. He worked on his “invention” for half of a day and then proceeded to take profiles. Howard improved on the machine’s design over the next week then, happening upon an itinerant profilist, replaced his own homemade machine by making a trade for the machine of the other artist. Then he set out to make his fame and fortune as a silhouettist. Howard did quite well as a last minute artist. He traveled and worked in much of Maine and showed up in the New York City Business Directory for the years 1813 and 1816. We have no records for other cities, but we assume he worked in other parts of New England. There are no known silhouettes by Howard with a handwritten signature, but a few of his silhouettes have been found with 2 different embossed signatures, EVERET HOWARD. We know that he bought one signature stamp in Brunswick, Maine. We are aware of one pair of watercolor profile portraits by Howard. They are signed with one of two impressed signature stamps that we know existed.

Everet Howard’s silhouettes are wonderful examples of just how creative a machine-traced silhouette can be. The profiles are sharp and lifelike—indeed technically very well-done. But what creates the great distinction in Howard’s silhouettes are the flourishes he used as additions within and outside of the cut profile. We have solid evidence of three bust-line terminations used by Howard. The most common (which I will call Type 1) includes part of the sitter’s arm to which the front of the bust-line curves up to meet the front of the arm. The Type 1 bust-line essentially has a half-moon cut upward at the arm and one cut downward at the front. The second bust-line (Type 2) has two half-moons cut so that they might be compared to a cursive “w”. The bust-line used in the watercolor profiles we know of is also Type 2. The third (Type 3) is comprised of 2 half-moons curving upward—basically the opposite of Type 2. Type 3 is often found with drawn circles or dots below the bust. Howard varied the depth of the half-moons so that, with the drawn dots, one might miss the middle point of the cut when viewing.

Howard added painted and drawn flourishes such as hair, shirt fronts, and lace collars that are eye-catching and well-done. He was a master at these flourishes. We know of two silhouettes in which Howard cut an embellishment below the bust-line for no other purpose than a bit of lagniappe for the viewer. Howard sometimes, by seldom, cut hair by slashing strokes of a pen-knife. Howard often painted or drew circles or dots around the profile of women. Sometimes the circles were only below the bust-line and other times he completely edged the profile with circles. As odd as it sounds, the circles really complement the profiles. He drew hair and clothing details, sometimes in ink or watercolor and often in pencil.

Howard's style shows how a machine-traced silhouette can be enlivened after the tracing with creativity and artistic flourish. The lucky few who own the rarely found silhouettes by Everet Howard own American folk art treasures. Rarely are they found with the embossed signature, but much of Howard’s work is so distinctive that with study, it can be easily attributed.

References:

Payne, Suzanne Rudnick & Michael R. and McClard, Peggy, “Shadow & Scissors”, The Magazine Antiques, Jan. 19, 2018, online article at https://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/shadows-and-scissors/.

Lester Ward Parker, “Diary of a Young Man, 1807– 08”, The New-England Galaxy, vol. 7, no. 1 (Summer 1965), pp. 31–42. Article based on diary of Everet Howard.

Please view the Howard silhouette currently in offered on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

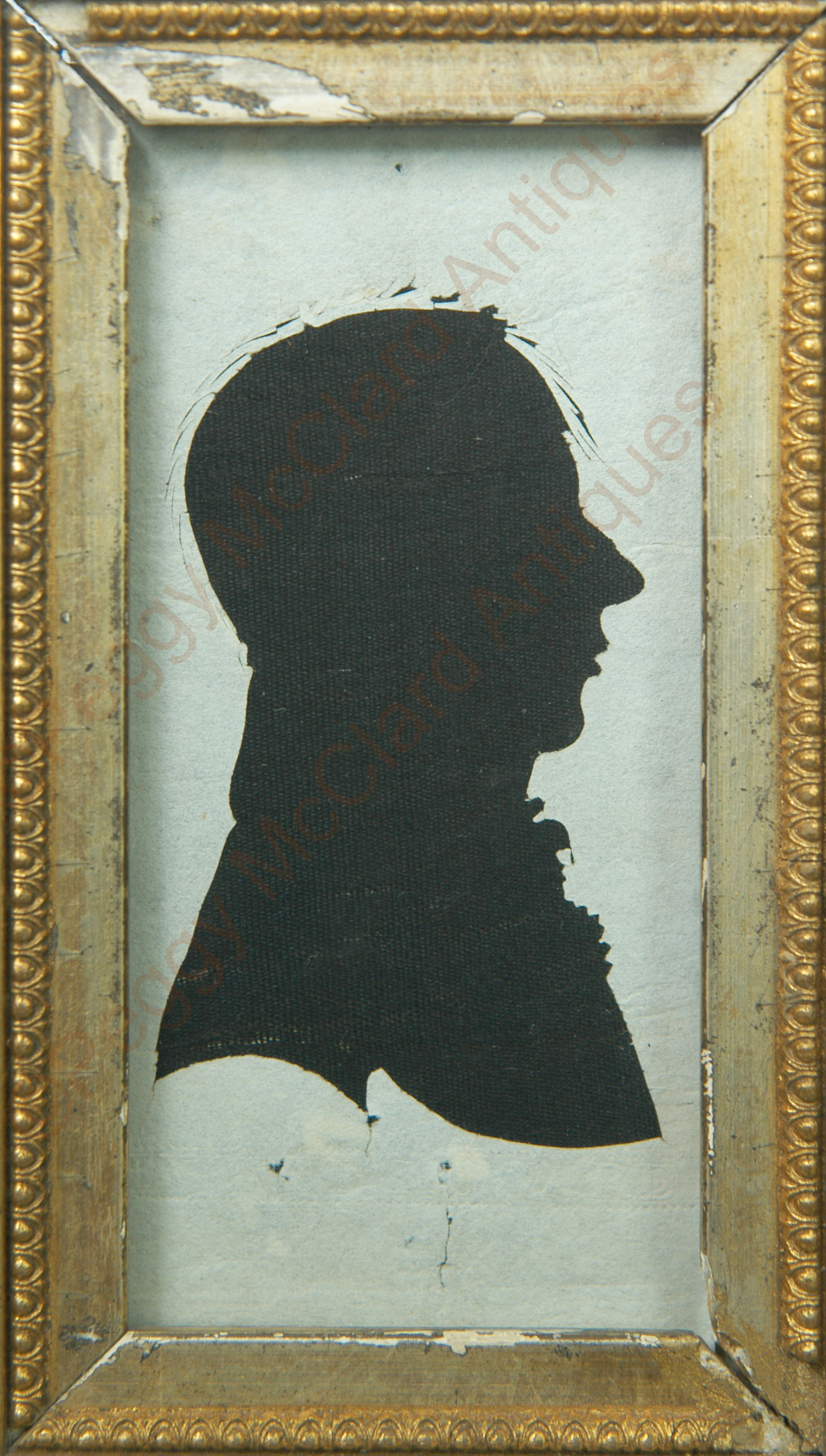

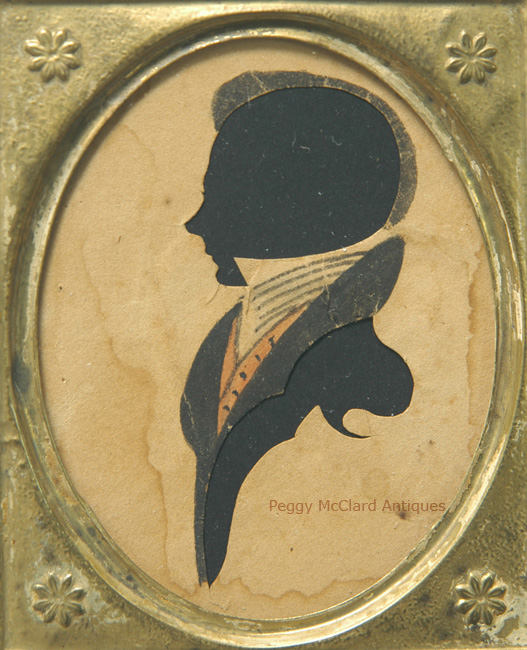

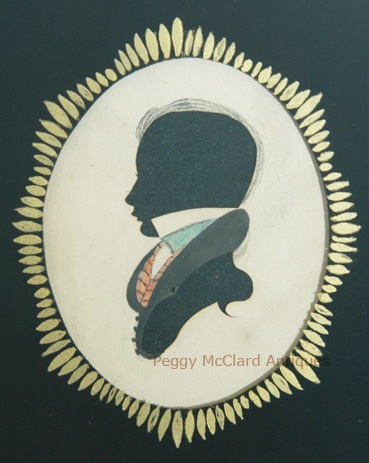

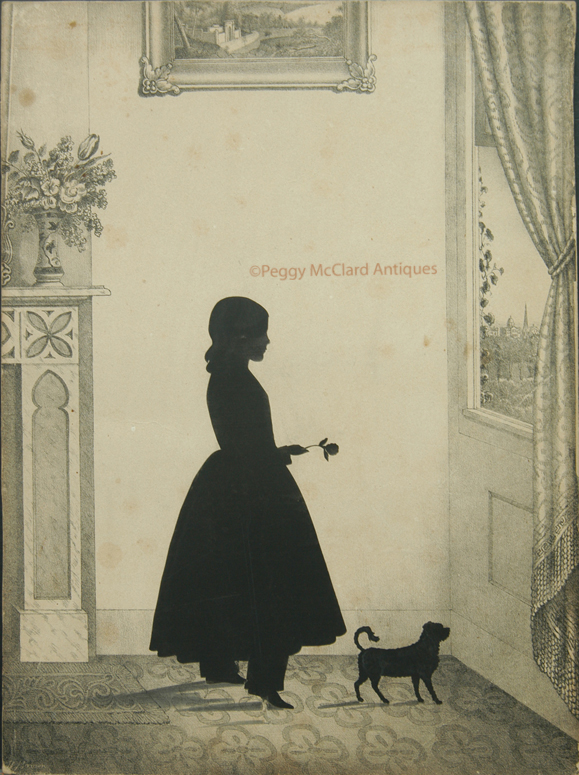

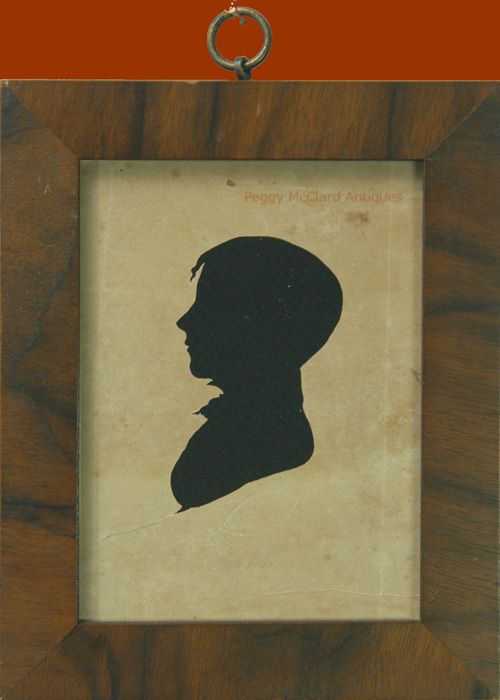

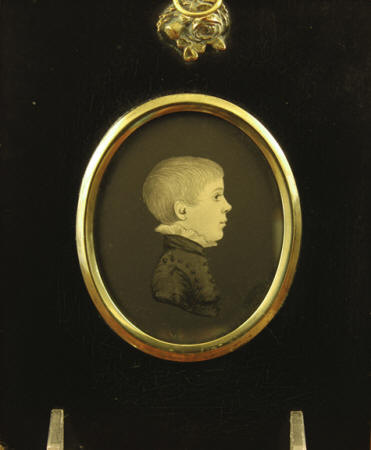

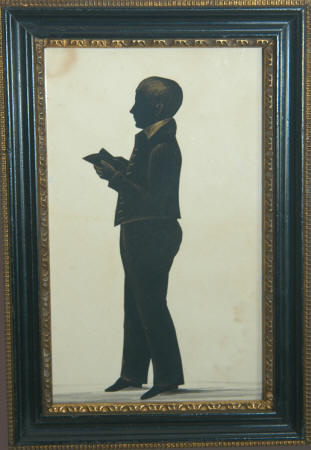

Master William James Hubard, Child Prodigy Silhouettist (1807-1862) and The Hubard Gallery (active 1823- circa 1845)

Born in Whitchurch Shropshire, England Master Hubard began cutting silhouettes at 12 years of age. He was a celebrated silhouette artist (some say an exploited child prodigy) even before he came to America in 1824 at the ripe old age of 17. By the age of 15, Master Hubard had been called upon to cut the silhouettes of the Duchess of Kent and Queen Victoria (who was still a slender little princess at the time). In 1823, the editor of a newspaper in Norwich exclaimed “We do not hesitate to pronounce Master H. the greatest phenomenon of art that this city ever witnessed, . . .”

In 1824, he landed on American soil in New York at the ripe old age of 17. In New York Hubard set up the Hubard Gallery at 24 Coney Street and charged 50 cents per profile. I've only seen one silhouette which Master Hubard hand-signed ("James Hubard"). His silhouettes are generally stenciled “Hubard Gallery” onto the back, use an impressed mark stating simply “Hubard”, or either the silhouette or frame is backed by one of numerous printed trade labels. After Hubard left, the Gallery used impressed stamps saying “Hubard Gallery” or “Taken At The Hubard Gallery” and also numerous trade labels continuing to tout the talent of Hubard even though the silhouettes were being cut by other artists.

Full-length silhouettes cut by Hubard are more commonly found than busts. Although the earliest were not embellished, Hubard became a master at gilt embellishment before the end of his silhouette career. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Master Hubard never relied upon contraptions or machinery for aid in cutting his silhouettes—only common scissors. His silhouettes are always cut & paste.

In 1827, Hubard broke from his manager (known only as "Mr. Smith") and took up portrait painting under the tutelage of Gilbert Stuart. We know from his letters that he occasionally continued to cut silhouettes even after becoming an accomplished portrait artist. During the 1850s, Hubard became interested in sculpture and established a foundry in Richmond, Virginia for casting bronzes. When the Civil War started, Hubard turned his attention to inventing and producing an explosive for use by the Confederate Army. He was killed at his foundry by an exploding shell.

McKechnie tells us that Hubard's early manager, Mr. Smith, continued to run the Hubard Gallery as a going concern until about 1845. We know that Master Jarvis (or Jervis) Hankes (or Hanks) was cutting silhouettes for the Hubard Gallery before Hubard broke with Smith. McKechnie believed that Hankes continued with the Gallery for some years after Hubard left. McKechnie also found evidence that Samuel Thomas Gill advertised himself as having at onetime worked for the Hubard Gallery. The fact that the Hubard Gallery employed several artists and the fact that Hubard continued to occasionally cut silhouettes both in America and abroad makes it very difficult to determine the origins of silhouettes cut after 1823.

References:

Hansen-Knarhoi, Megan, "'Silhouette of man 1' - Taken At The Hubard Gallery", NelsonMuseum.co.na

Please view the Hubard and Hubard Gallery silhouettes currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

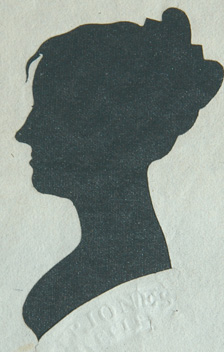

T.P. Jones (active First Quarter 19th Century)

Little is known about the American silhouettist T.P. Jones. He may be the artist that Mrs. Jackson refers to as "F.P.Jones" in her book Silhouettes A History and Dictionary of Artists. In 2007, ebay sold a pair of silhouettes clearly stamped "F.P. JONES / FECIT". Since I did not see the F.P. Jones pair in person, I can not vouch for their authenticity as a 19th century pair. It is possible that a company such as Foster Brothers created the pair as a reproduction, using Mrs. Jackson's reference as their example. Dictionary of Artists in America 1564-1860 by Groce and Wallace says of T.P. Jones, "Silhouetteist working in the vecinity of Schenectady (N.Y.) in 1808. Cf. F. P. Jones ¶ Baker, "The Story of Two Silhouettes," repro." Of F.P. Jones, Groce says, "Itinerant silhouettist of early 19th century, New England. Cf. ___ Jones, portrait painter at NYC in 1818 and T.P. Jones, silhouettist at Schenectady (N.Y.) in 1808. ¶ Carrick, Shades of Our Ancestors, 120." Are T.P. and F.P. Jones the same person? I do not yet have the answer to that.

Thanks to the research of Sue Anderson, we do now know that T.P. Jones and Isaac Todd worked together in New York City from at least April through June 22, 1805. They advertised on April 1, 1805, in the American Citizen that they had united for profile likenesses on William Street. On June 22, 1805, the two artists advertised in the Republican Watch Tower, that they had removed to Maiden Lane. By August 13, 1805, Jones advertised alone in the Evening Post of NYC.

According to the family history passed along with one of the silhouettes that I once owned, T.P. Jones was still working in New York City in 1826 when he cut the silhouette of Elizabeth Read(e), second cousin, once removed, to General George Washington.

T.P. Jones work beautifully executed hollow cut bust length profiles with a sloping bust termination. His sitters have a small cut eyelash and his women usually display a delicate lock of hair above the forehead. They are quite scarce and heavily sought by collectors.

-

-

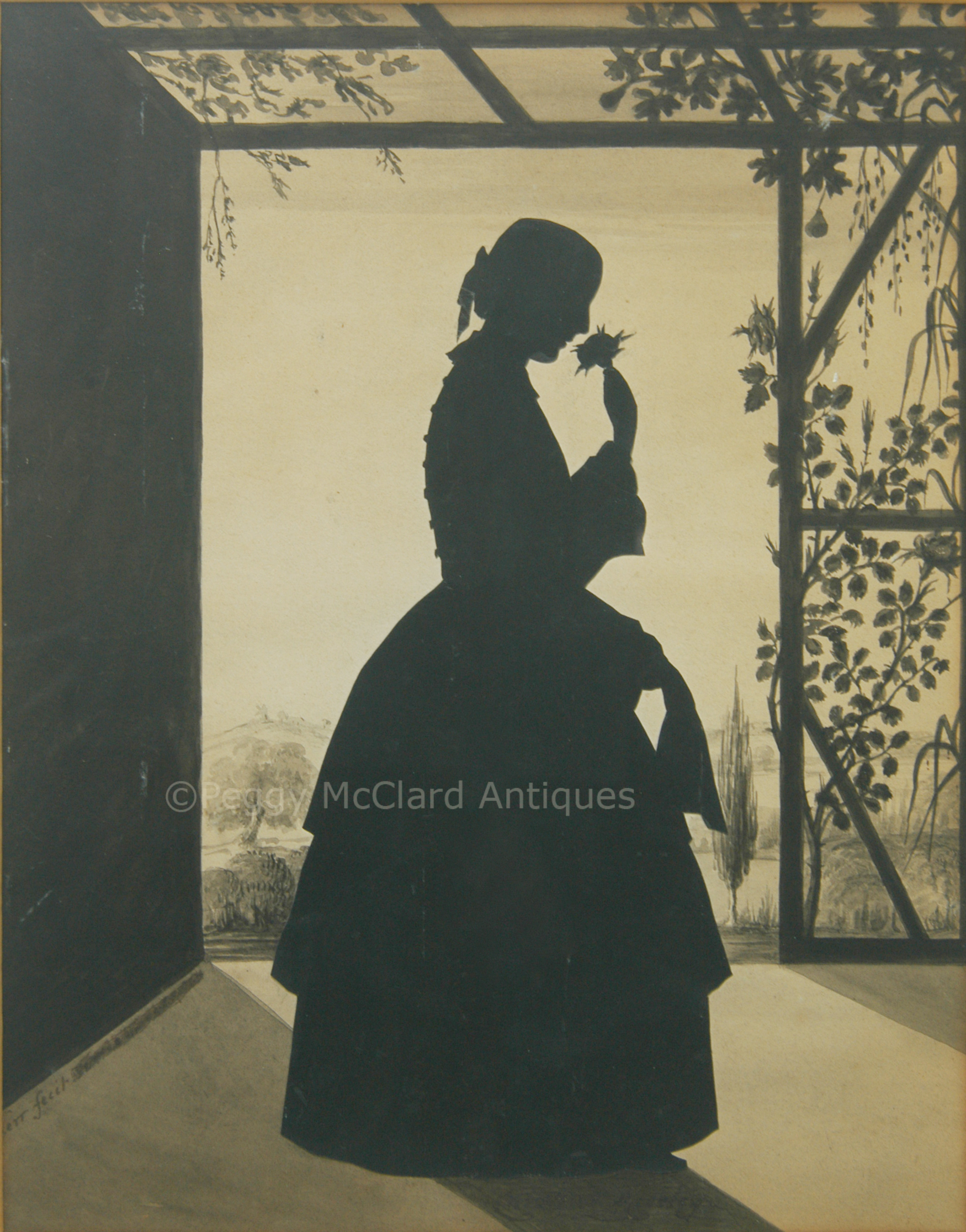

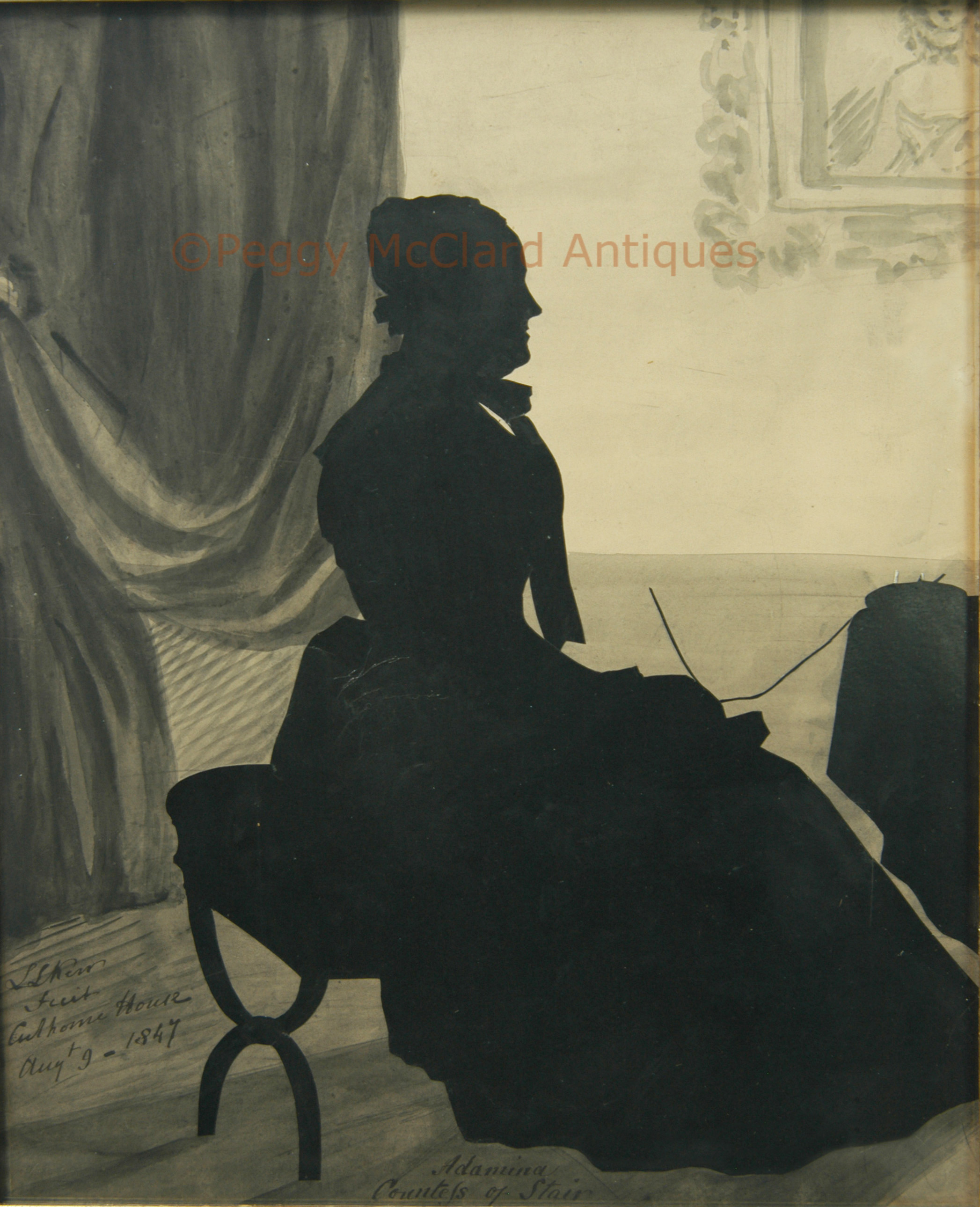

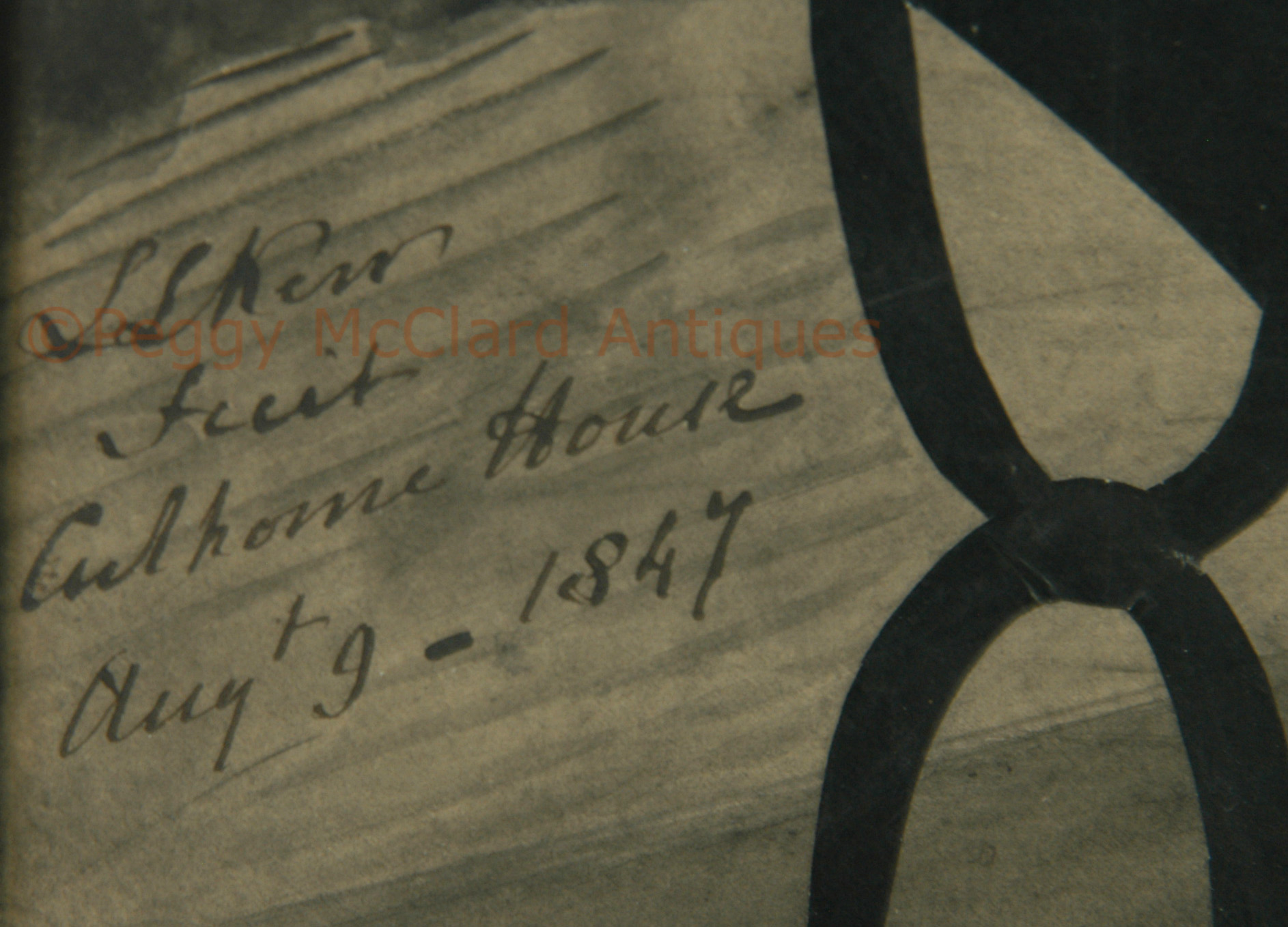

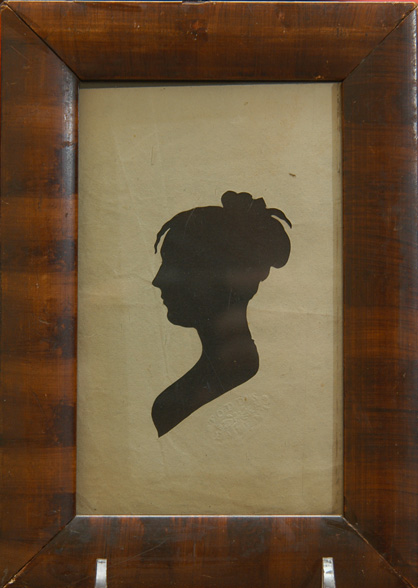

Lady Louisa Kerr (active 1825-1868)

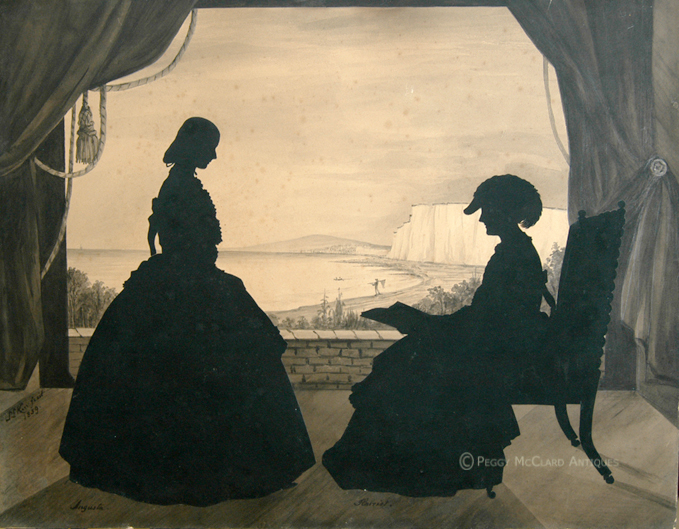

Lady Letitia Louisa Kerr was born in London in 1800 and baptized in Marylebone as Letitia Margaret Kerr, the name chosen for her by her aristocratic parents, Lord Mark Robert Kerr (third son of the Marquis of Lothian) and Charlotte MacDonnell (daughter of the Earl of Antrim and later the Countess of Antrim). It was the artist, herself, who later changed her name to Letitia Louisa Kerr. Lord Mark Kerr was a gifted amateur artist, painting watercolor landscapes and caricature drawings. Louisa had seven brothers and five sisters. Two of her brothers inherited the title of Earl of Antrim after their mother died and both changed their last names to MacDonnell, their mother’s family name. The title exists through today in the McDonnell family (note that the family has dropped the “a” from the spelling of their name) and family members continue to live at the family home Glenann Castle in Northern Ireland. Artistic talents still run in the family. One descendent, Hector McDonnell is a well-recognized artist.

Growing up during a time when most girls were educated at home, it is not surprising that we have found no evidence that Lady Louisa ever went to school. But her great love of and talents for art were seen early. We know that she was cutting silhouettes by the time she was 18 years old (in 1818) and that she was painting in watercolors at least by 1821. Lady Louisa remained unmarried (and took care of her aging parents until their deaths) until 1871 when she married widower Capt. Cortlandt George MacGregor Skinner. Lady Louisa never sold her artwork but she seems to have cut or painted profiles at most gatherings of her aristocratic friends and family. She painted wonderful watercolor backgrounds on which to place her full-length silhouettes and did us the honor of naming each sitter along with her signature and where the piece was created. There are a very few known examples of fully painted silhouettes, one being a self-portrait that also includes her step-uncle riding horses. Almost all of Lady Louisa’s sitters were either women or children. This fact fits with the time when men left the women to visit with each other after formal dinners. Lady Louisa cut silhouettes until at least 1868. She died in 1885. Her silhouettes are greatly sought-after and extremely scarce on the market.

Please view the Kerr silhouette currently in stock on the Antique Silhouettes page.

-

-

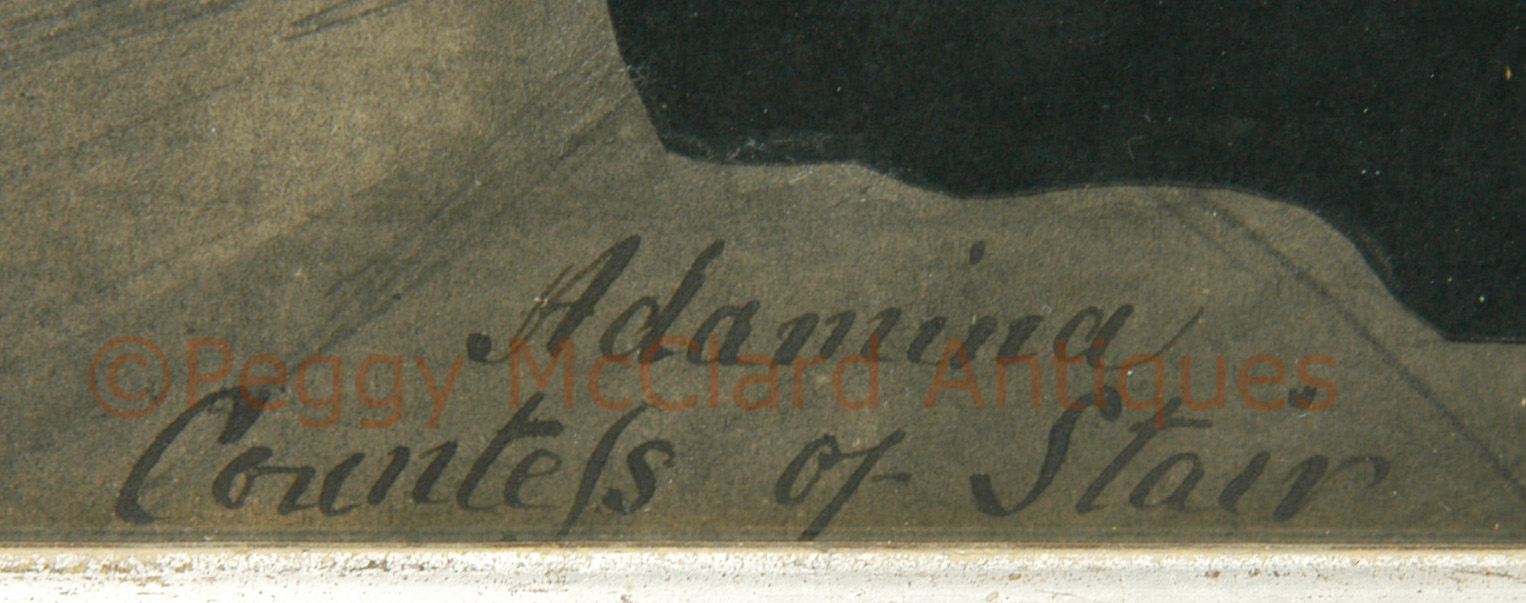

Lady Louisa's Signature

Lady Louisa's Signature

-

Lady Louisa's Inscription Identifying the Sitter

Lady Louisa's Inscription Identifying the Sitter

-

-

-

William King (known activity 1804-1806)

William King was a man of many talents but, as some might say, with a wayward disposition. We know King as a cabinet maker, turner, and profilist. He was born sometime in the last half of the 18th century in Salem, Massachusetts. While considered by many to be a genius, he also bore the qualities of a scamp.

In 1785, King was mentioned in the diary of Reverend William Bentley as living with King’s father-in-law, Deacon Phippen. A 1787 diary entry by Rev. Bentley stated:

A William King related to the family of Hodges, Webb, Stone & Mason by their wives, after having been long absent in the West Indies, about four years ago returned, and married a daughter of Deacon Phippen, by whom he had one child & the prospect of another. This W.K. being very capricious left his family, without any warning wrote a letter of his intentions to abscond, without be pressed for debt, or other visible reasons. He was pursued, apprehended near East Haven in Connecticut, by the owner of his Sulky & Horse, gave his note for 16 pounds damage, and has returned again after a fortnight’s absence.

Alice Van Leer Carrick, Shades of our Ancestors, pgs. 46-47.

In 1789, King was apparently still living with his family since he was advertising in the Salem Mercury as an ivory-turner selling canes, dice, backgammon boards, billiard balls and the like.

Then in 1796, Rev. Bentley wrote:

News from Philadelphia, that Wm. King, belonging to a good family in this Town, after having dragged his family from Town to Town, left a note that he meant to drown himself and disappeared. It is supposed that he means to ramble unencumbered. The family are to return to Salem.

Through known advertisements, it appears that King began cutting profiles around 1804. In that year, his advertisements also mentioned his turned works of ivory, wood and iron. In 1805, King advertised in Boston and no longer mentioned his turnings. In 1806, he was in Hanover, NH and claimed to have cut more than 20,000 silhouettes in Salem, Newburyport, Portsmouth, Portland and all of their adjoining towns.

Despite King’s boast of cutting so many silhouettes, examples are difficult to find and much sought after. In her important book Shades of Our Ancestors, Ms. Carrick called him one of her favorite hollow-cutters. As she said, King had a knack of “seeing people agreeably.”

-

-

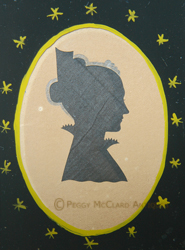

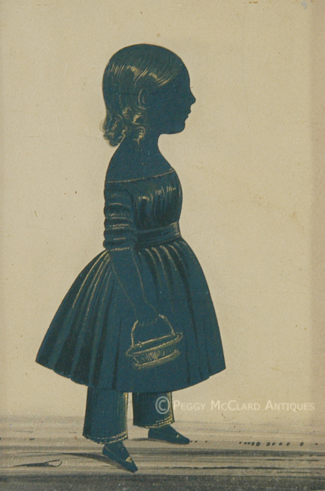

AttributedMerryweather (active circa 1850)

Little is known about the artist Merryweather. The rare examples of his or her work shows that Merryweather cut silhouettes in black paper against a watercolor wash base composed of concentric circles. The figures are lightly brushed embellishment of gold. Children are represented with toys or baskets of flowers. Mrs. F. Neville Jackson mentions a trade label, but does not give detail. Sue McKechnie states that the Merryweather in her collection had a handwritten inscription, "By Merryweather, Profilist" on the verso. She also tells us that the silhouette illustrated in her book (extremely similar to the figure shown here) bore the handwritten inscription, "Cut by Merryweather, Profilist".

-

-

Samuel Metford (1810-1890)

Samuel Metford was born in 1810 to a Quaker family in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. He moved to America around 1834 and became a naturalized American citizen. Metford seems to have centered his profile cutting in Connecticut although he is also known to have worked in New York and South Carolina. He likely also plied his trade in other states. Metford continued working in until 1844 when he moved back to England. He made two more trips to America in between 1865 and 1867. It is unknown whether he cut profiles during the later trips to America as no examples have been found that appear to date to the 1860s. Most books list the date of Metford’s death as 1890. However, Sue McKechnie states that Metford died in 1896.

Although Metford generally placed his cut & paste silhouettes on watercolor wash backgrounds, some examples have been found with lithograph backgrounds. He signed his silhouettes as either “S. Metford” or “Sam’l Metford.”

Metford’s work is sought for its rich embellishments which he perfected to a much greater degree than most 19th century silhouettists. He embellished his silhouettes in either gold, Chinese white, or yellow-ochre watercolor.

-

-

John Miers (1758-1821) and John Field (1772-1848)

John Miers is considered the finest silhouettist of the 18th century. Miers’ father was a painter by trade, having purchased a business which did “Coach Painting and Undertaking for Funerals in general as usual.” Although the young Miers helped his father in the business, there is no evidence that this artist who is considered one of the greatest profilists in the history of art ever received formal artistic training. His painted silhouettes on plaster or ivory are prized by astute collectors.

In 1781, the young, recently married Miers began his own business as a painter, gilder, and profilist in Leeds. He advertised that he took “Most striking Likenesses taken in One Minute upon an entire New Plan.” After 5 years of advertising his “new Method” or “Peculiar Plan (which is allowed superior to any other in the Kingdom),” Miers hit a snag when he discovered that Miss Mary Lightfoot, the daughter of one with whom he had lodged had traveled to Scotland and attempted to establish herself as a profilist by copying his techniques. He fought against Miss Lightfoot’s theft with a very explicit advertisement condemning her activities. It appears that his advertisement worked, as Miss Lightfoot seems to have disappeared from the scene.

In 1791, Miers began using the trade label which backs the offered silhouette and is known as “Trade Label No. 11.” This label was used from 1791 until c. 1810. When Trade Label No. 11 came into use, Miers ceased to be the only artist working under his name. In fact, most of the silhouettes of this period were painted by others.

During this period, John Field began working for Miers. Field proved to be the most talented of the silhouettists working under Miers and by 1823 Miers son, William, and Field became partners in the studio of Miers and Field.

Field’s silhouettes are distinctive in the transparency of the ruffled areas of the sitter’s clothing and by the characteristic dip at the back of the curved bust-line. These features would remain a distinctive quality in Field’s work for the rest of his career. Later in his career, Field painted silhouettes on card with great flourish, detail and bronzing. While working for Miers, however, his silhouettes on plaster were in black with white added only for transparent detailing at the edge of the silhouettes, or light bronzing on silhouettes painted on ivory.

-

-

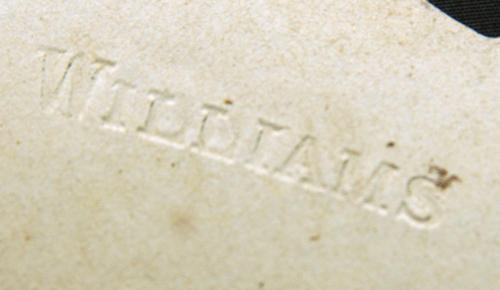

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) and Moses Williams (1777-about 1825)

Charles Willson Peale, born in Chestertown, Maryland, is perhaps the most famous of the American-born profilists, and certainly known as a jack-of-all-trades. Known as the “Artist of the Revolution” he is most well known for his wonderful oil portraits of the most important of our country’s ancestors, including George and Martha Washington, and Revolutionary War General Horatio Gates.

Peale was a saddler, harness-maker, clock and watch-maker, silversmith, artist in oils, crayons, wax, and miniature. He was a soldier, legislator, lecturer, taxidermist, and dentist. He married a succession of wives and had children with all of them. A true artist, Peale named his children after artists who had blazed the way before him: Raphael, Rembrandt, Rubens, Titan, and Van Dyke were the names of some of his sons.

Peale opened his Museum of Natural Science and Art in Philadelphia in 1795. The prehistoric bones, taxidermy animals, and plant life that he exhibited became so popular that he was forced to find larger quarters for his museum twice. In 1802, Peale moved his popular museum into the second floor of Independence Hall. Here he added a silhouette business which used a physiognotrace patented by his friend John Hawkins to make hollow cut silhouettes. The majority of the silhouettes from the Independence Hall museum are stamped with the embossed signature “MUSEUM.” Less common is “PEALE'S MUSEUM” stamped above the form of an eagle (please see the note below about spotting fake "PEALE'S MUSEUM" silhouettes. The rarest of the three stamped signatures used by Peale is “PEALE.” We are unsure of the dates in each of the stamps were used nor of which is his eventual three museums, run by his sons, used the scarcer two. It is thought that Rembrandt Peale may have used the "PEALE" stamp at the separate Baltimore museum. Raphaelle Peale also cut silhouettes in Virginia and must have used one of these stamps.

While living in Maryland, Peale acquired a mixed-race slave couple, probably as payment for a portrait commision. According to law which he helped to pass, Peale freed the couple when they turned 28. Their 11 year old son remained bound to the Peale family , which, of course, kept the parents also bound to Peale. Peale took the young slave, Moses Williams, into the family home and treated him almost like another son. Interestingly, Peale could have emancipated Moses early, but chose to keep control over him--much like he kept control over his son's lives throughout their adulthood.

Moses Williams was taught the art of silhouette cutting. Under Peale’s supervision and tutelage. Williams cut most of the silhouette that are signed “MUSEUM.” While many people assume that the silhouettes of statesmen cut during this period were done by Peale himself, Rembrandt Peale once said that Williams' business was so extensive that he amassed two barrels full of blockheads "among which were frequently found, by careful search, the likenesses of many a valued friend or relative, and sometimes of distinguished personages -- another source of profit to him." Rembrandt Peale, Notes and Queries. The Physiognotrace (1856), 308. Peale was fiercely defensive of Williams against any prejudices of museum visitors and credited the physiognotrace’s reputation for correct likeness in part to the “perfection of Williams’ cutting.”

Peale emancipated Williams in 1802, when he was 27. Earning a mere 6 to 8 cents per silhouette, Williams eventually bought a two-story house. He married the Peale family's white cook (who would not let him sit at the table with her before his emancipation) and together they had a daughter. He continued working managing the Philadelphia silhouette cutting business until his retirement. Williams is remembered as one of the earliest known African-American artists in the United States.

Spotting fake "PEALE'S MUSEUM" silhouettes:

The most faked silhouettes in the world have the impressed signature "PEALE'S MUSEUM" under a spread eagle. That is because, in the early 20th century, a couple of unscrupulous antiques dealers named Collins found the original stamp. They set about making horribly cut fakes and stamping them with what had been one of the most rare of stamps from Charles Willson Peale's Museum. The fakes are easy to spot (although they come up for sale all the time as original pieces). First, the silhouette cutting is sloppy and the subjects are quite often George Washington and other great statespersons. Second, the paper used by Peale's real tracing machine was 3 1/2" x 4 3/4". The size of Peale's paper could not vary because his tracing machine was set up to hold a 3 1/2" x 4 3/4" piece of paper and automatically reduce the size of the profile while it was being traced around the actual person. The fake silhouettes are on paper that tends to be 6" x 8"....it is impossible that this size paper was used in Peale's tracing machine. Last, the impressed signature stamp for the real silhouettes sits right below the bust line termination....it had to because the paper was not much bigger than the actual cut profile. The impressed stamp on the fake Peale's sits well below the bust line termination....in an apparent effort to even out the extra expanse of blank space created by such a large piece of paper (even though the figures were cut much larger than the real Peales). The fake Peale's Museum silhouettes are very predominant in the market while the real ones are quite scarce.

Please view the Peale Museum silhouettes currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

Puffy Sleeve Artist (active 1830-1831)

This is a recognized and highly sought-after American silhouettist whose work makes me happy and shows the great creativity of American folk silhouette artist of the 19th century. We don't know who the Puffy Sleeve Artist was, but he or she left behind a wonderful legacy of unique naïve silhouettes with hollow cut heads atop watercolor bodies. The profiles are all three-quarter length with women always facing left and men always facing right. The heads of women sit high above their bodies with long necks that give room to highlight their necklaces and fichus. Hair is added above the head with India ink or watercolor. The dresses are always painted, usually blue or black. The women's hair combs are cut into the hollow cut and sit high above their head. The right hands of the women rest at waist length and the left hands hold an accessory such as a book, purse, parasol, or flower. Books often bear the initials or age of the sitter and a date. Like the women, men have their hair painted around the hollow-cut head. The left hand is frequently in the man's pocket or resting at hip length. The right hands of the men holds a decorative object such as a hat, book, cane or even a trumpet. Hands of both women and men appear to be gloved. Many have been found in gilded frames with an inset rope, leading some to believe that these were the only original frames used by this artist. I believe that enough have been found in originally sized period frames that this artist may have used a number of different frames. Itinerant artists often bought frames from different frame-makers as they worked their way along their routes. All recorded dated examples bear the dates of 1830 or 1831. Examples have been found in New Hampshire, Vermont and Massachusetts. Work by the Puffy Sleeve Artist is so desirable that unknowledgeable (or unscrupulous) sellers often mislabel silhouettes in which women wear leg-o-mutton sleeves as work by this artist. This artist's work is unique and there is only one other anonymous artist who did work similar to this.

Anderson, Marna A Loving Likeness American Folk Portraits of the Nineteenth Century, (Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. (1992) 44-47.)

-

-

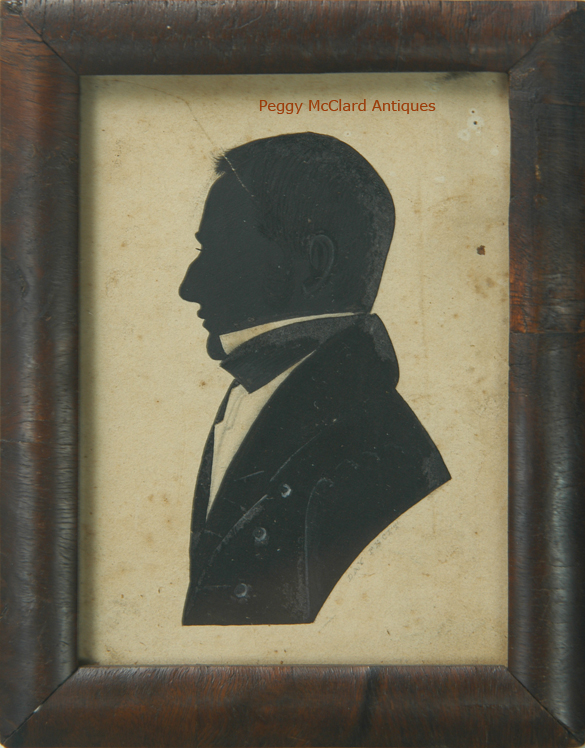

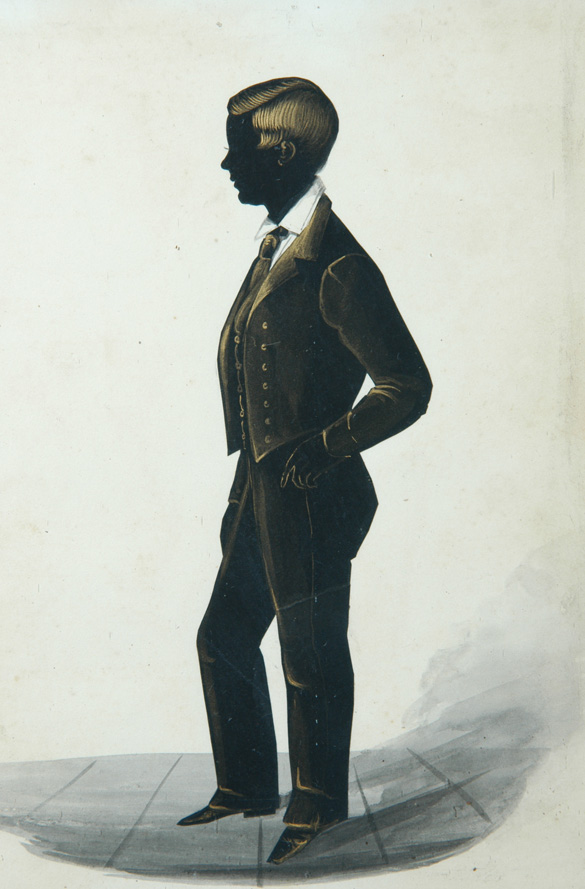

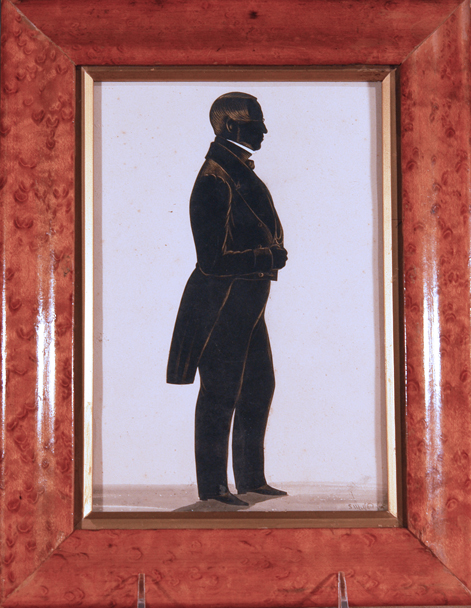

Royal Victoria Gallery - F. & H.A. Frith (after 1837-1854)

The Royal Victoria Gallery was managed by three artistic members of the Frith family. Brothers Frederick (who used the signature "F.") and Henry Albert (known as "H.A.") touted their talents as “PAPRYOTOMIST[s] to His Late as well as to her present Most Gracious Majesty, and to whom most of the brilliant Court of the United Kingdom have sat for Their Likenesses. . .” They claimed to have cut “many Thousand Likenesses” and to being able to complete the cutting with their “Talismanic Scissors” in only one minute. The brothers often advertised that they were joined in their travels by their father, “Mr. Frith, Senr.” “whose Talents as a Portrait and Miniature Painter are too well known to need comment.” Both brothers are known to have cut silhouettes. It is unlikely that Frith, Sr. cut profiles, but it is assumed that he may have done some of the bronze work on the more elaborately embellished silhouettes.

The embellishment of the Royal Victoria Gallery silhouettes is of the highest quality. Unless a signature identifies one of the brothers, it is impossible to know which brother may be responsible. It is also generally assumed that the Friths had unidentified assistants who may have helped with the cutting and/or bronzing. Sue McKenzie notes in her book, British Silhouette Artists and their Work 1760-1860, that signed examples tend to show that Fredrick Frith was capable of painting backgrounds in a more finished style than his brother. Also, the bronzing in some of F. Frith’s signed examples exhibits more expertly rendered work with more extreme highlighting than H.A. Frith’s signed work.

One feature common to full-length male figures produced by the gallery is the stance in which the men are shown standing with their feet apart, with the far leg bent at the knee. Although full-length female figures have legs hidden under skirts, the feet apart stance is commonly seen with the lady’s background foot pointed to the side and the front foot pointed forward.

Please view the Royal Victoria Gallery & Frith silhouettes currently in stock on the Silhouettes page.

-

-

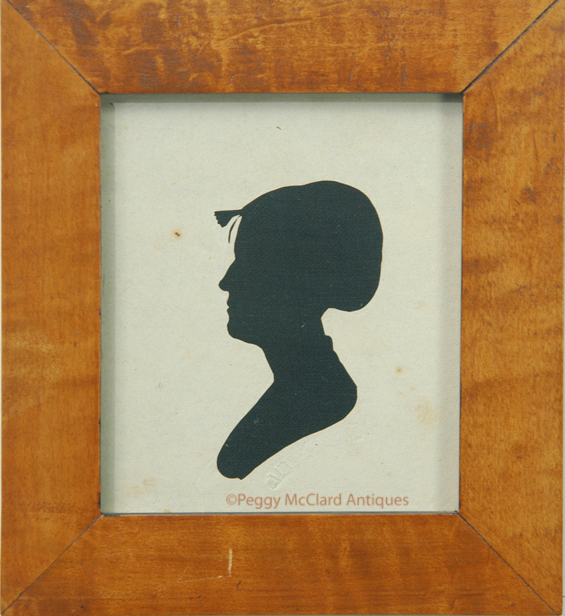

Justin Salisbury (active circa 1825-1835)

Justin Salisbury was a Vermont resident, who worked primarily inthe Connecticut River Valley. Unlike most hollow cut silhouettists of the period, it appears that Salisbury worked freehand, without the aid of machines such as physiognotrace. We believe this because his work does not exhibit an incised or penciled line bordering the edge of the profile, as most mechanically drawn profiles exhibit. Salisbury's work is often embellished with penciled details, such as the hairstyle embellishments in this silhouette. The sawtooth border of this young lady's neck ruff and the wave at the bust termination are characteristic of Salisbury's work. Salisbury cut his men with hollow cut heads, uncut collar and coat lapel, then hollow cut shoulder, much the same as William Chamberlain's cutting. However, whereas Chamberlain and most similar works of the period colored the lapel with watercolor, Salisbury used pencil to color the lapel. He drew a very simple stock with ink. The bust termination of Salisbury's men is a straight line, slightly angled up toward the back, with a small downward notch about two-thirds toward the back to depict the arm.

Howe, Florence Thompson, "Justin Salisbury's Silhouettes", Spinning Wheel, March 1971. 54-55. Click here for a pdf version of the article.

Sloat, Caroline F., ed., Meet Your Neighbors New England Portraits Painters & Society 1790-1850, Old Sturbridge Village 1992. 93-95

-

-

Georges-Hyde Seigneux (1764-?)